Mr Piotrovsky:

To my profound regret, I have not received a substantive answer to the letter I addressed to you on January 12. I raised some specific questions but, instead of a professional conversation, have received in return only an obscure quote from your catalogue preface, and accusations along the lines of ‘what nonsense.’ By refusing to engage in dialogue you deny the right to discuss the actions of Hermitage staff, and effectively declare them infallible. Such a management approach is, I feel, dangerous – not least for the future of the Hermitage itself. By failing to rectify its mistakes it will swiftly lose its status as one of the world’s leading museums, and be reduced to a mere depository for valuable goods.

An exhibition of blatant forgeries in what is not only a State museum, but a museum of the people, entrusted to your care – that is what my letter was about. If you do not care for the manner of my approach it can easily be changed, but that would not alter the heart of the problem. I would like to hear some serious arguments from you and engage in a discussion. A ‘what nonsense’ sort of answer is not worthy of your museum and, going on the interest in the issues I raised among the press and public, you have an obligation to address your visitors, and society, in your role as Director of the Hermitage – and reply truthfully to the questions I asked you. The Hermitage is not your personal fiefdom: you are just a transient figure in its long history. The Hermitage embodies our history and is the pride of Russia. This museum belongs to the world’s cultural heritage. Your ‘Fabergé’ exhibition is dragging it through the gutter.

I am ready to explain calmly and in detail why I believe some of the items in this exhibition are fakes. I will start with the so-called ‘1904 Wedding Anniversary Egg’ but, before considering the subject in detail, I need to make a few introductory remarks.

‘Fabergé – Jeweller to the Imperial Court’ Exhibition Catalogue

As you know, jewelled Easter Eggs were produced by the House of Fabergé from 1885 to 1917 – first by order of Tsar Alexander III, then by Tsar Nicholas II. During Alexander III’s reign a single egg was made each year as a present for his wife, Empress Maria. From 1895 two eggs were made annually: one for the wife of Nicholas II, Empress Alexandra; the other for his mother, Dowager Empress Maria. There was an exception to this sequence in the years 1904 and 1905, when no Easter Eggs were completed or delivered to the Tsar.

The whereabouts of 44 Imperial Easter eggs are known today. There is scientific consensus as to their authenticity. The largest ensemble – ten eggs in all – is to be found in the Armoury Chamber of the Moscow Kremlin. Nine imperial eggs belong to the Fabergé Museum in St Petersburg; they were acquired from the Forbes Collection, having been thoroughly researched at the time of purchase. One unfinished egg, known as the Constellation Egg, was discovered in the Fersman Mineralogical Museum in 2001. Its authenticity, supported by numerous studies by leading Russian experts, is beyond doubt. All the other eggs are in private or public collections abroad.

The only egg to come to light since the Constellation is the Golden Clock Egg from 1887. It was discovered in 2011 and confirmed as genuine after prolonged examination.

So it would be scant exaggeration to call the discovery of a new, previously unknown Fabergé Easter egg an extremely rare and important event for dealers, collectors and researchers alike – comparable to the discovery of, say, a new Leonardo. Like any discovery of such magnitude it requires broad-ranging discussion and comprehensive coverage in scientific and journalistic publications.

Yet today in almost complete silence – as if we were talking about something frequent and banal – the Hermitage is presenting not one… not two… but six (six!) new Fabergé Imperial Easter eggs. Five are on show in the exhibition; the other, dubbed the ‘Karelian Birch Egg,’ is published in the catalogue. All six have the same owner; the exhibition features only part of his vast collection. Hermitage visitors are not shown the second Constellation egg, or other dodgy eggs from his museum in Baden-Baden (including, of course, the notorious ‘Fried Egg’).

- Fabergé Museum, Baden-Baden

- Fabergé Museum, Baden-Baden

- ‘Fried Egg’ (Fabergé Museum, Baden-Baden)

The ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ is, then, one of at least seven Imperial Easter Eggs unearthed over the past two decades by one and the same person. Its authenticity has not been assessed or publicly backed by any expert in Russia or abroad.

I shall proceed to outline the reasons why this item is a fake.

Provenance

The first thing that catches the eye when perusing the Hermitage exhibition catalogue is its lengthy description of the provenance of this ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg.’ This provenance is far more extensive and detailed than those given for the indisputable Fabergé originals owned by the Hermitage itself! The Egg was allegedly presented to Empress Alexandra by Nicholas II to mark their tenth wedding anniversary then, after the Revolution, entered the Kremlin Armoury before being sold abroad via Armand Hammer.

The history of Imperial Easter gifts is invariably supported by archival photographs, invoices and records of their movements and sales. References to them can be found in scientific publications like The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs – a catalogue raisonné published by Christie’s in 1997. Yet the Hermitage catalogue fails to reference any documents that prove the stated provenance of the ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg,’ either directly or indirectly. And this ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ is not mentioned in any known source – or in any of the very many books published about Fabergé. On what basis can the exhibition curators have concluded that this object has an imperial provenance ?

The answer is provided by the egg’s owner, Mr Ivanov, in a series of ‘documents’ he has circulated to dispel doubts about the truth of his breathtaking claims.

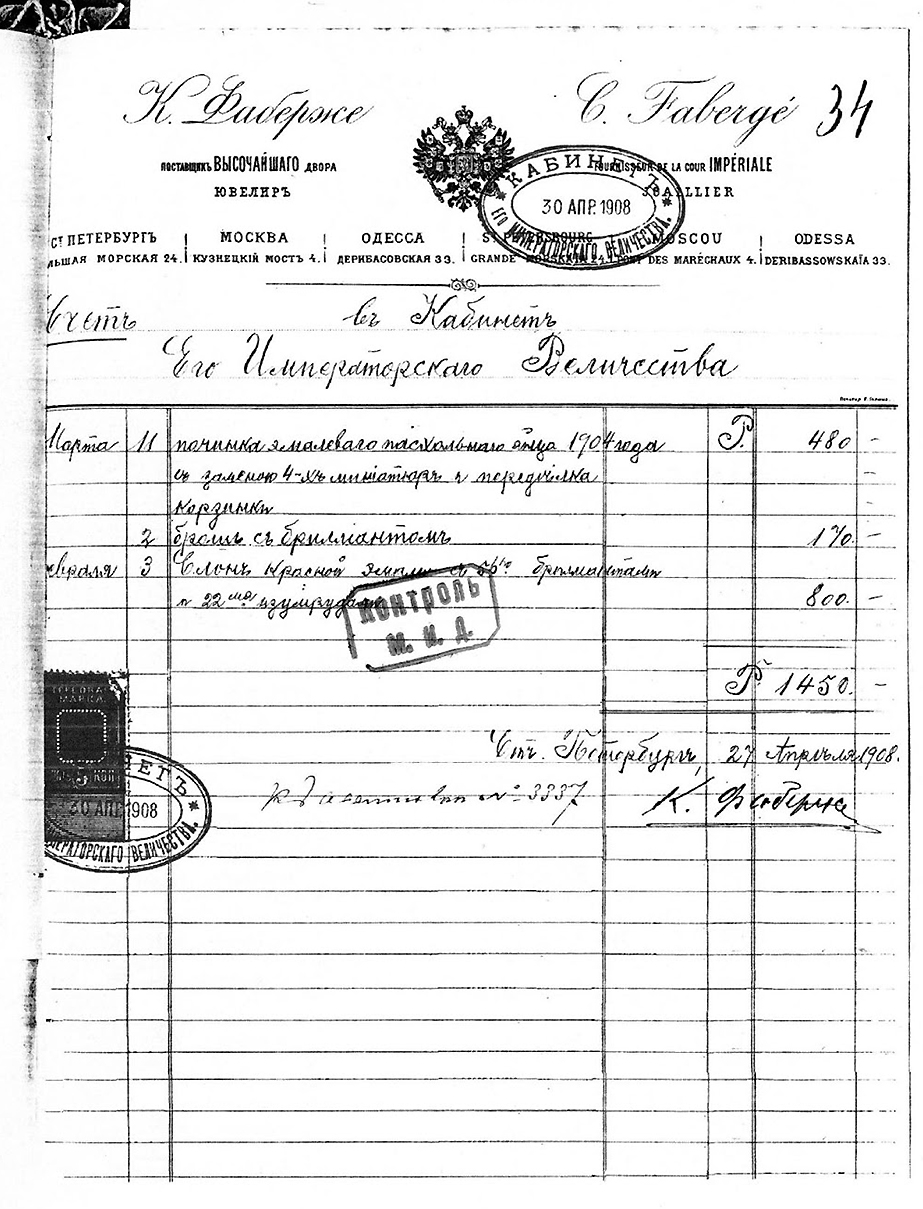

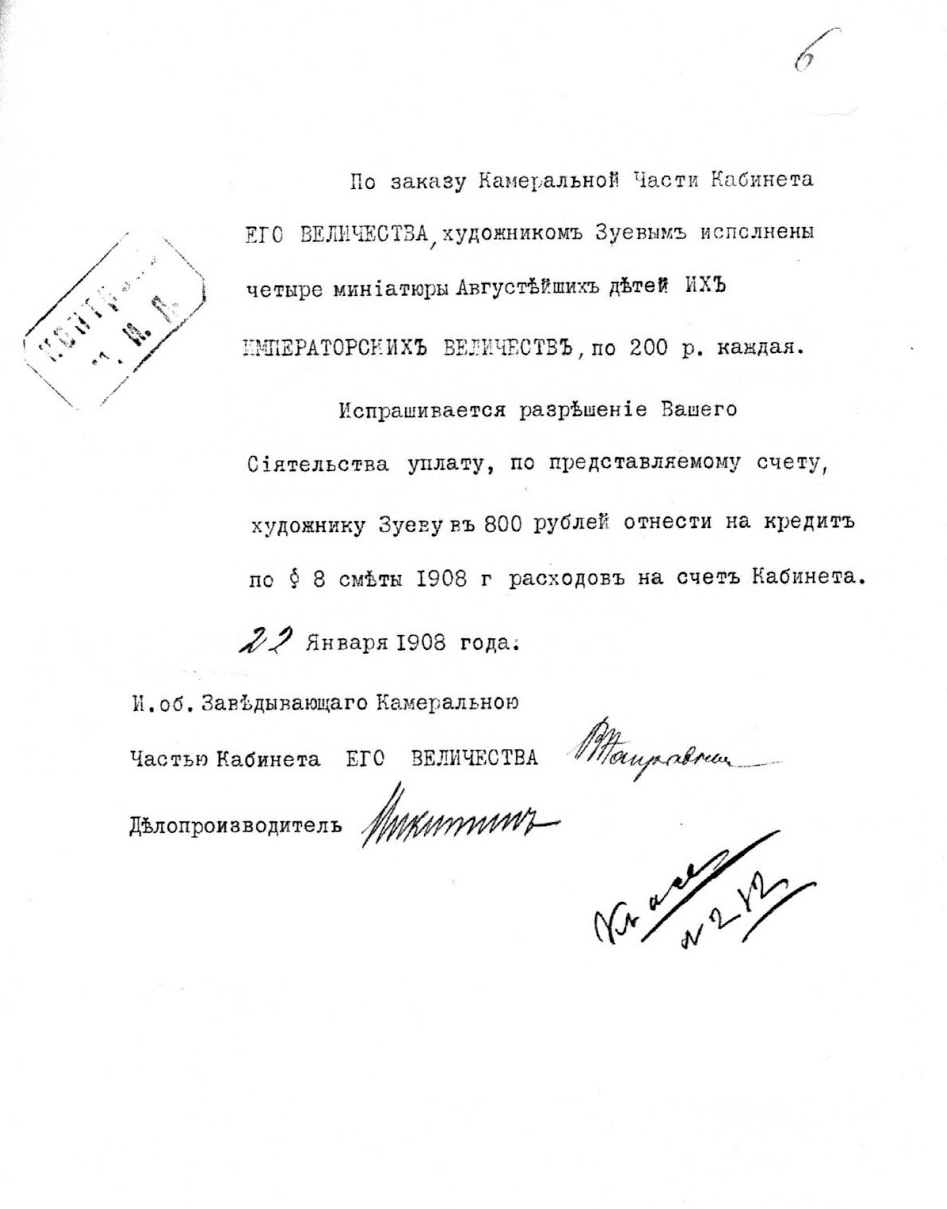

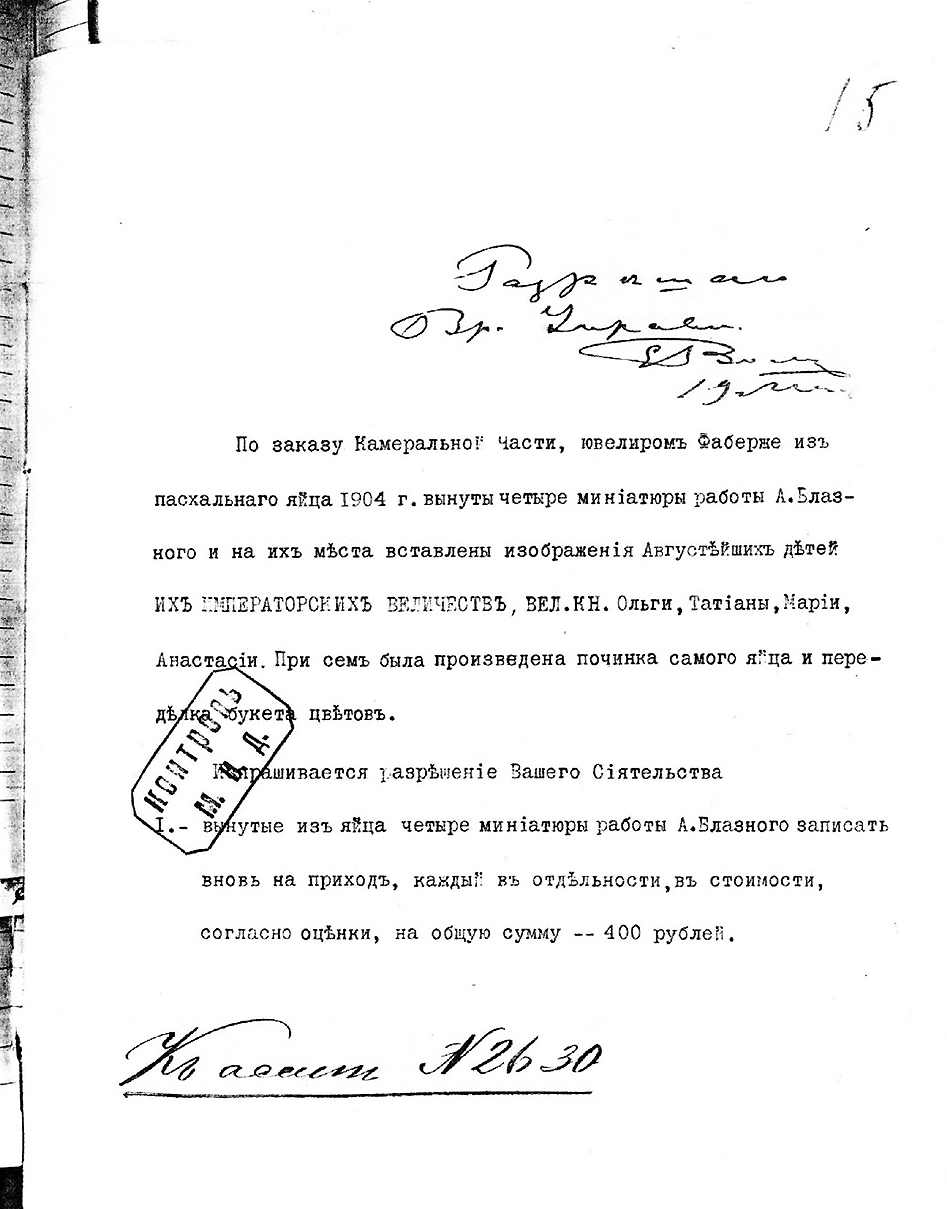

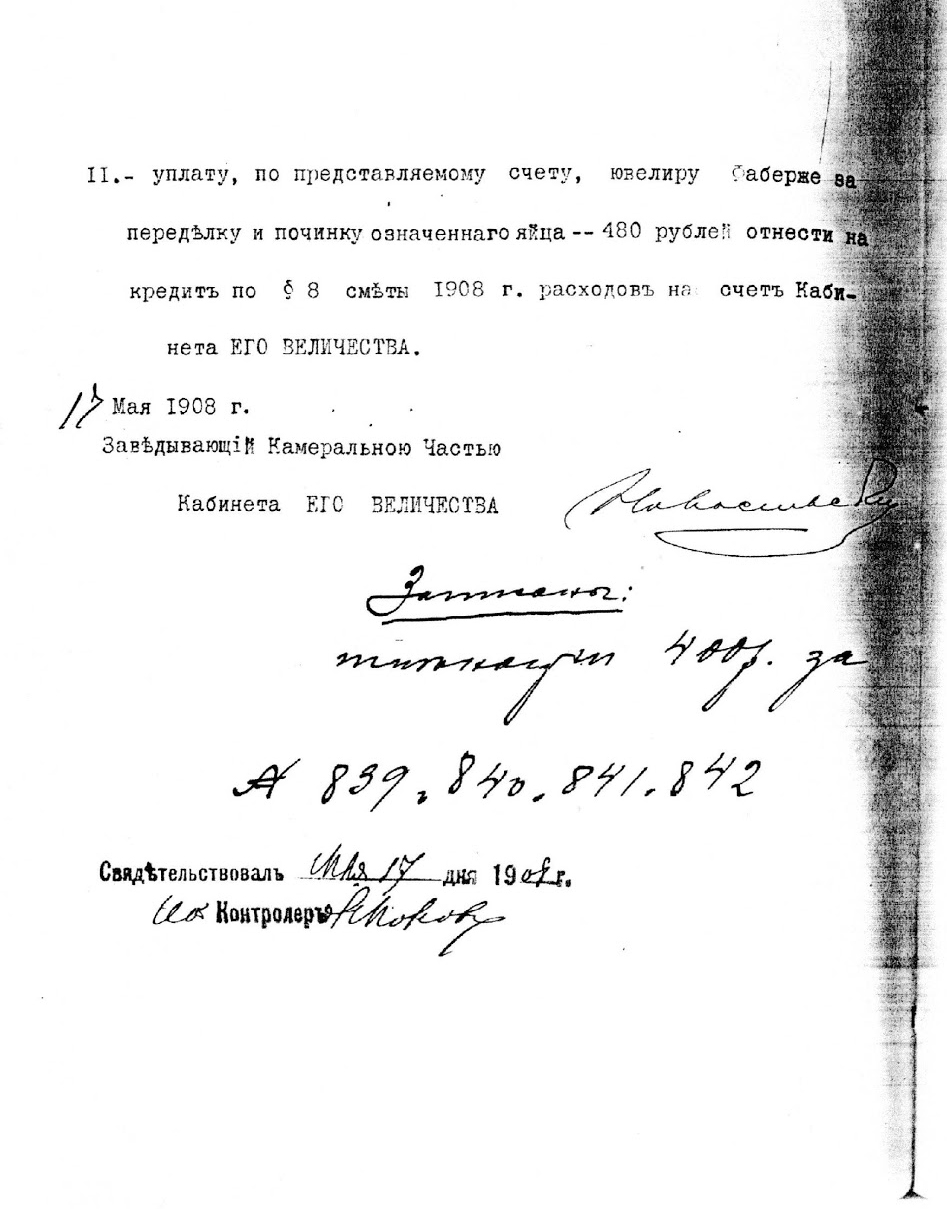

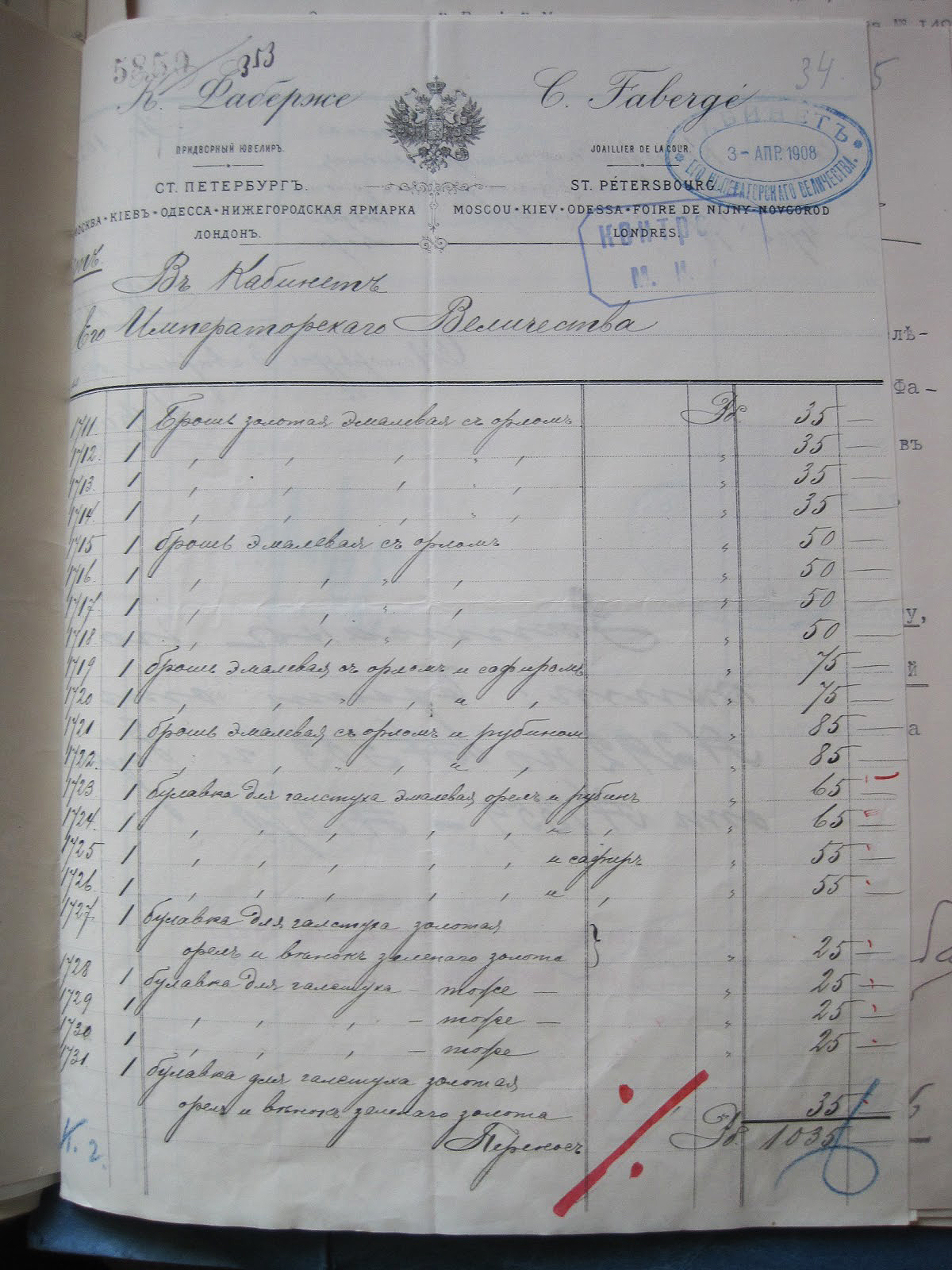

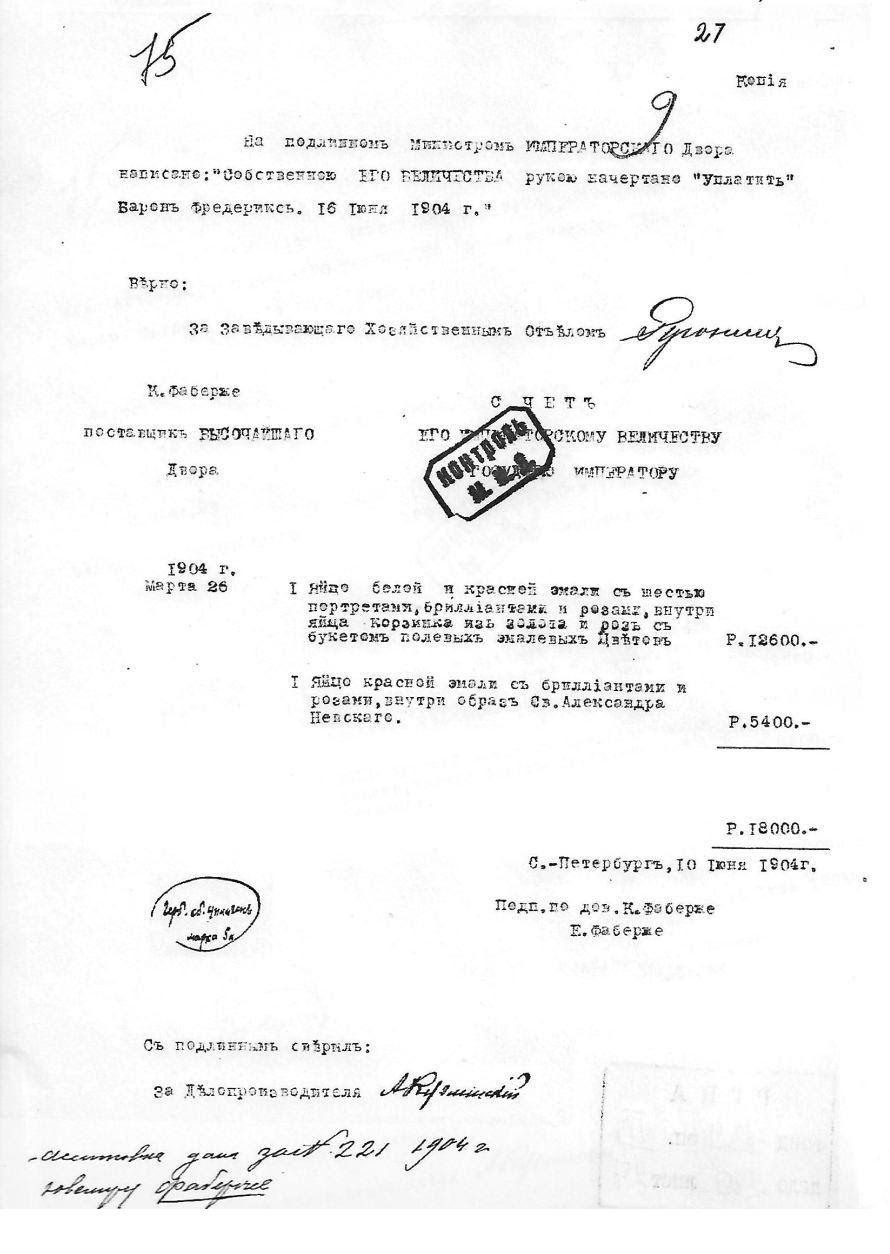

To support the notions of imperial provenance and a 1904 dating, he supplies a copy of a 1904 invoice for two eggs (I shall return to this second egg, which is also in the exhibition, at a future date); of another invoice, dated 30 April 1908, for repairing an ‘enamel Easter egg of 1904 by replacing 4 miniatures’; and a document stating that ‘four miniatures by A. Blaznov were removed from the Easter egg of 1904.’ Needless to say, none of these documents had ever come to the attention of any other researcher.

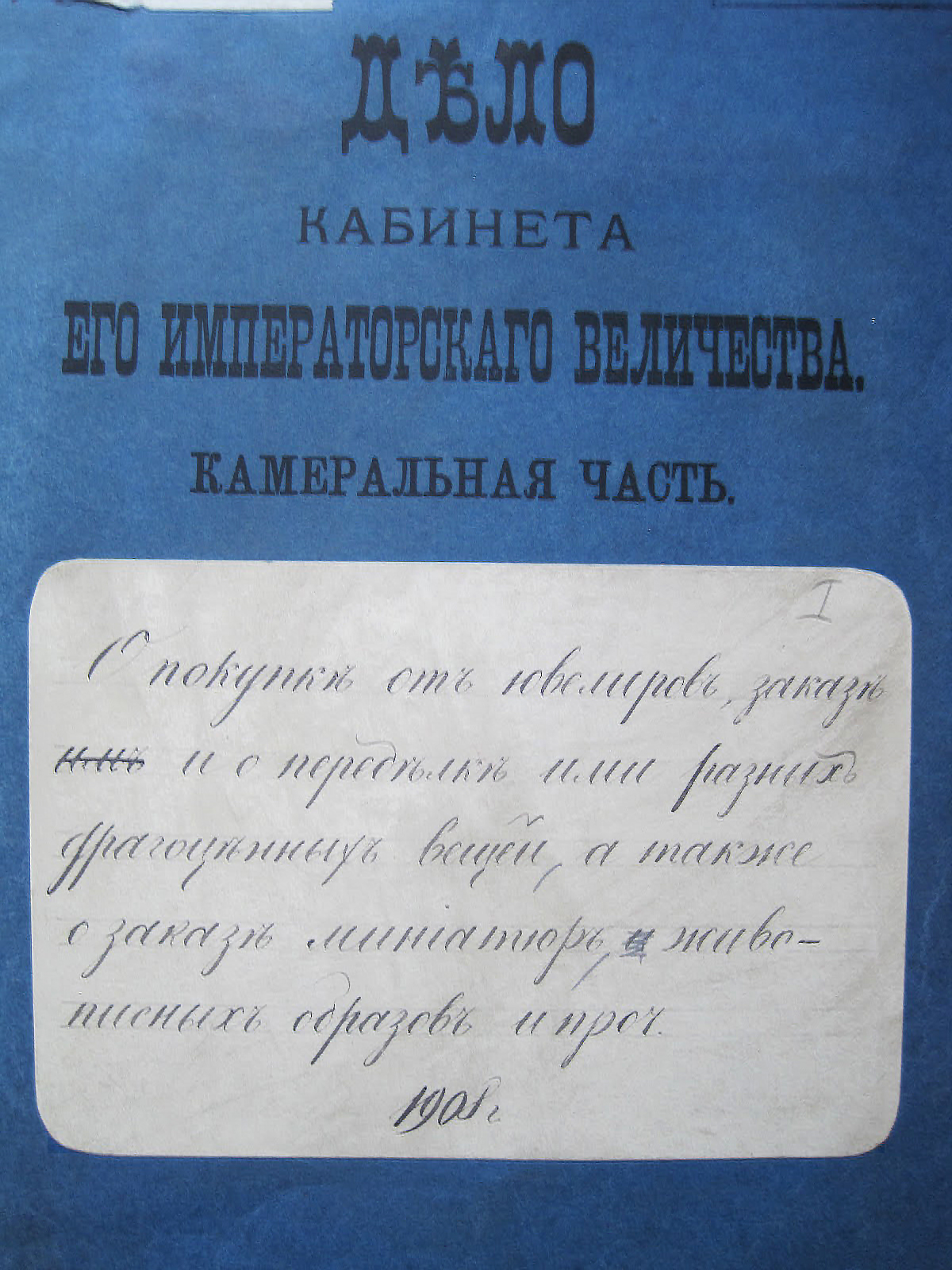

Mr Ivanov does not disclose how he managed to find documents no one else knew about, or indicate their origin: he does not give the name of the archive, or the numbers of the fund, inventory, box or page. So I decided to check the existence of such documents in the Russian State Historical Archives – but could find no invoices for making or repairing a 1904 egg. Here, for example, are sheets from file 468-8-953 ‘about the purchase of precious items from Jewellers to the Cabinet’ before 1908. They contain no mention of repairs to any eggs.

- Sheets from file 468-8-953 ‘about the purchase of precious items from Jewellers to the Cabinet’ before 1908

- Sheets from file 468-8-953 ‘about the purchase of precious items from Jewellers to the Cabinet’ before 1908

Furthermore, Mr Ivanov’s ‘documents’ contain obvious inconsistencies and absurdities. The miniaturist Alexander Blaznov, for instance, stopped working for the Imperial Cabinet in 1902 – so there is no way he could have made miniatures for a 1904 egg. The Blaznov miniatures supposedly removed are recorded in Ivanov’s document under numbers 839-842. The list of miniatures actually ends with number 450.

Then there is the assertion that the egg was in the Kremlin Armoury by 1920, remaining there until 1932. A 1920 entry date cannot be squared with documentary evidence. Imperial Easter Eggs were transferred to the Kremlin for temporary storage in 1922 – as revealed by Tatyana Tutova (Head of Manuscripts & Documentation at the Kremlin Museums) in The Fate of Palace Valuables from the Imperial House of Russia – Records of the 1922 Kremlin Commission. This 1922 Kremlin inventory still exists. It contains short but accurate descriptions of ALL Easter eggs presented to Empress Alexandra (including some now lost) and most of the gifts presented to Dowager Empress Maria. No Easter egg with miniatures from 1904 appears in the inventory.

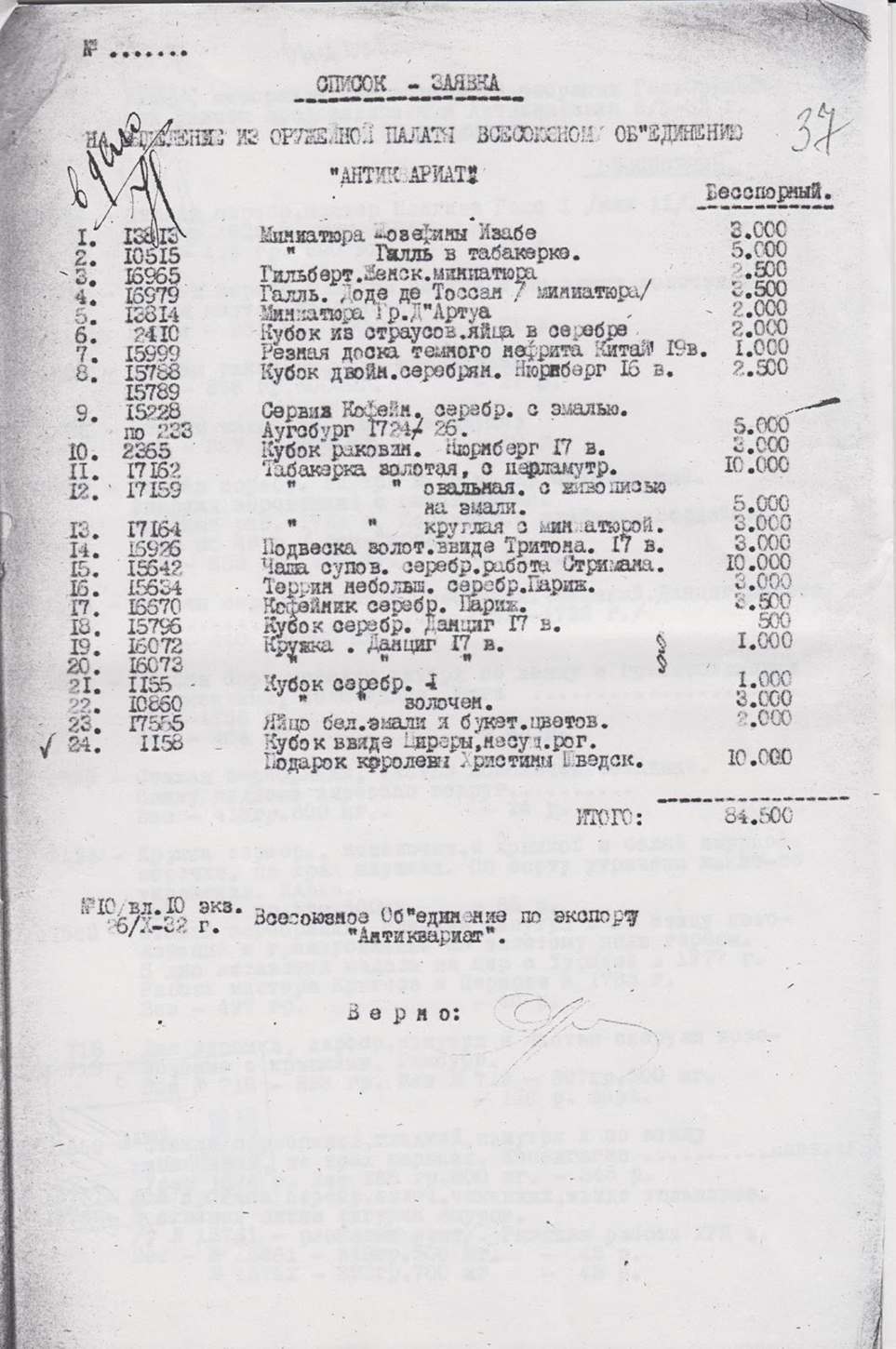

In trying to prove the impossible, Mr Ivanov provides an ‘application list’ for allocating 24 items from the Armoury Chamber to the ‘All-Union State Trading Office Antikvariat.’ The only Easter egg on this list appears as number 23, and is described as 17555 – white enamel egg and bouquet of flowers – 2,000 rubles. Mr Ivanov would have us believe this entry refers to the ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg.’ Nothing of the sort! This white enamel Easter Egg with a bouquet of flowers, with accession number 17555, was identified long ago. It is in Buckingham Palace, in the collection of the Queen Elizabeth II – as stated in Caroline de Guitaut’s Fabergé in the Royal Collection (London 2003, pp 36-37) and The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs by Tatiana Fabergé, Lynette Proler & Valentin Skurlov (London 1997, pp 156-158).

Subsequent owners of the ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ are said to include Armand Hammer; the wife of American industrialist Herbert William Hoover; and (from 1951 to 2008) an anonymous private collector.

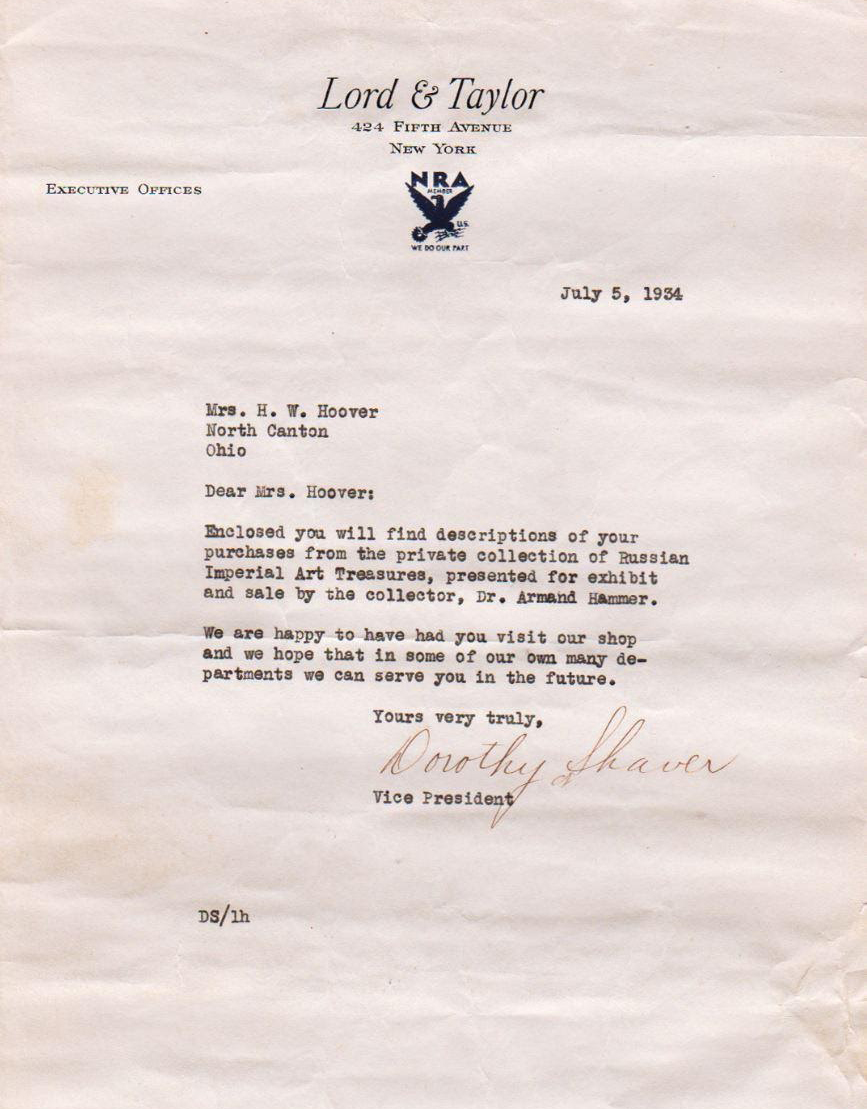

To convince us that the egg was exported from Russia and briefly belonged to Armand Hammer, Mr Ivanov provides a letter from the New York department store Lord & Taylor who, in 1933, staged a selling exhibition of ‘Russian Imperial Art Treaures’ that Hammer had brought back from the Soviet Union. Although it includes many works by Fabergé, the catalogue does not contain one word about a 1904 egg. Nor does Lord & Taylor’s letter, which merely evokes Mrs Hoover’s ‘purchases from the private collection of Russian Imperial Art Treasures.’

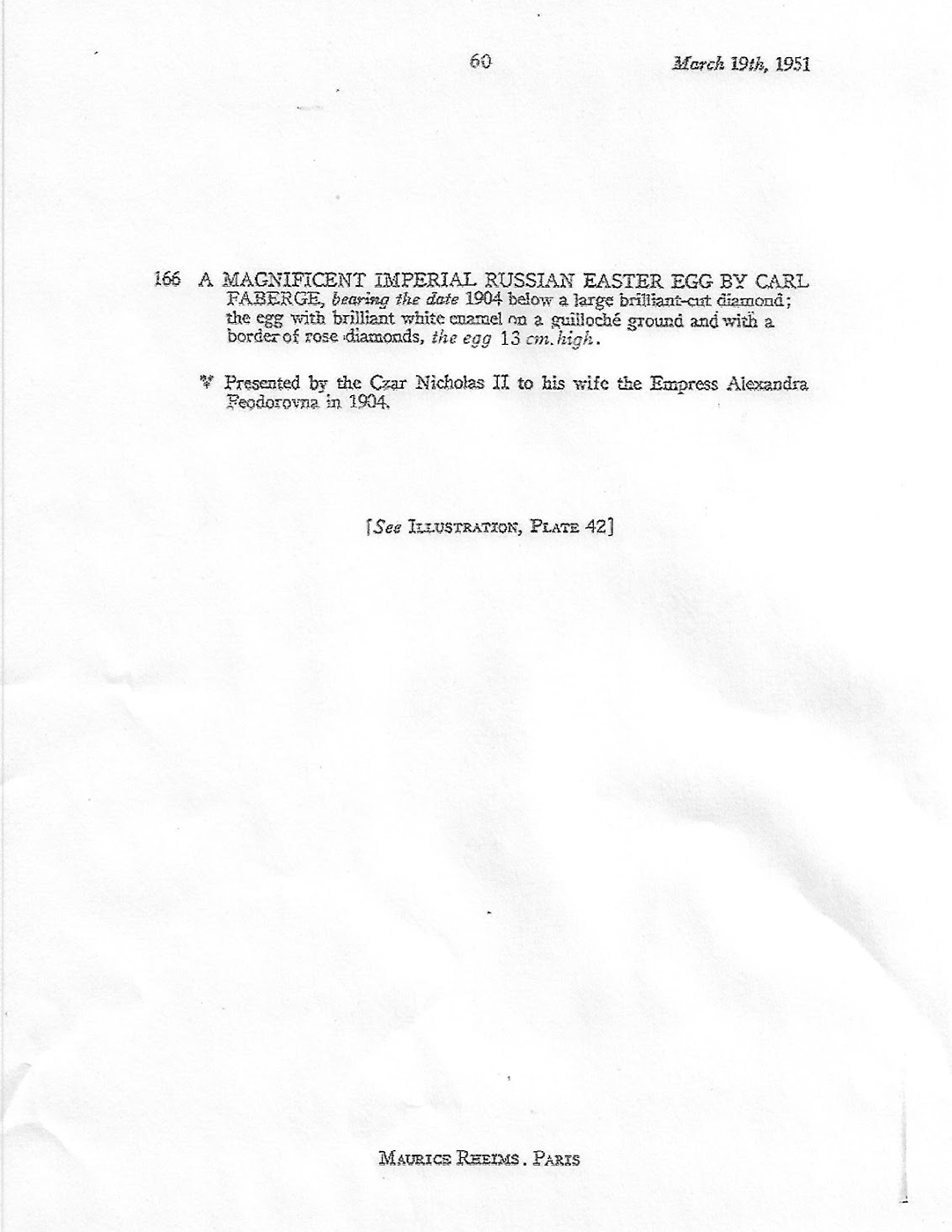

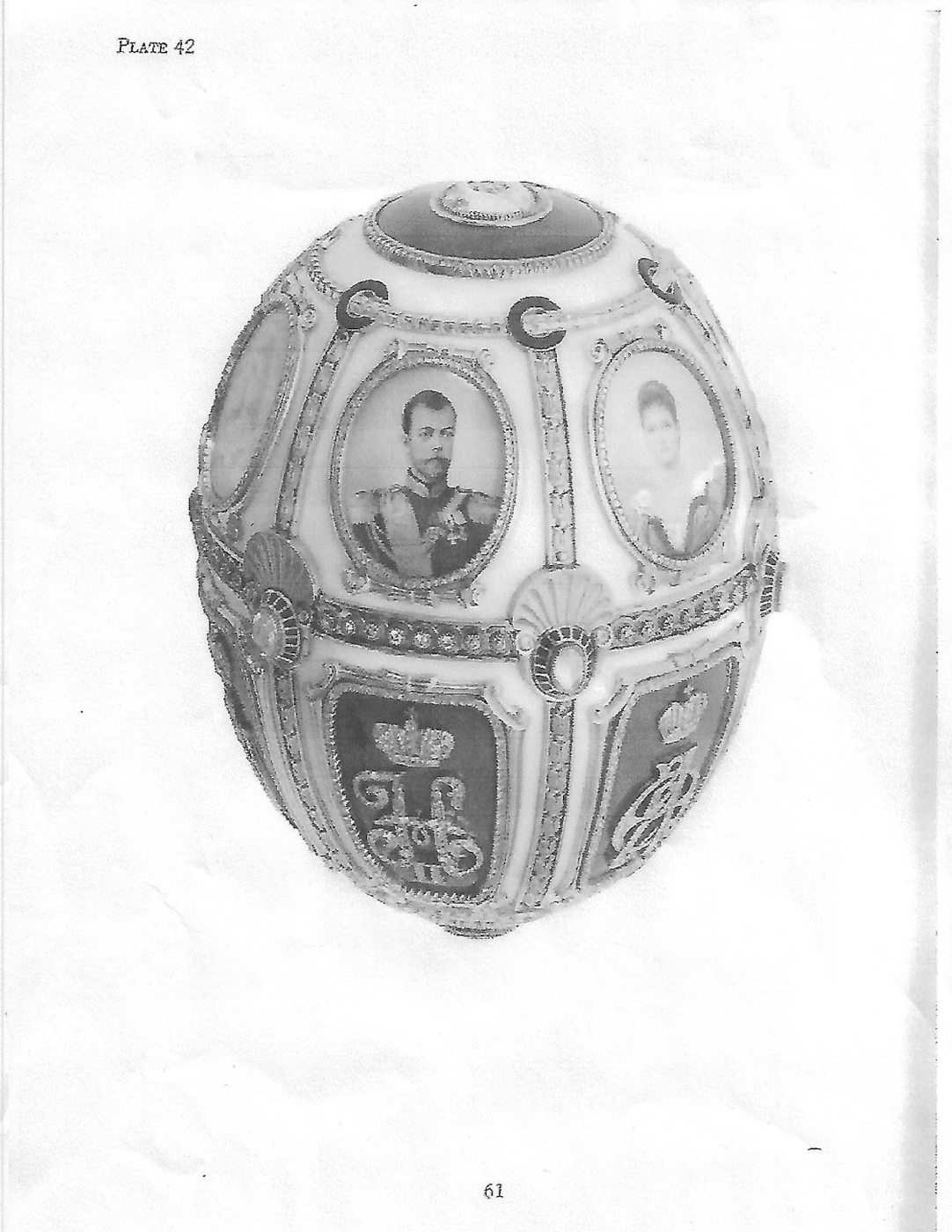

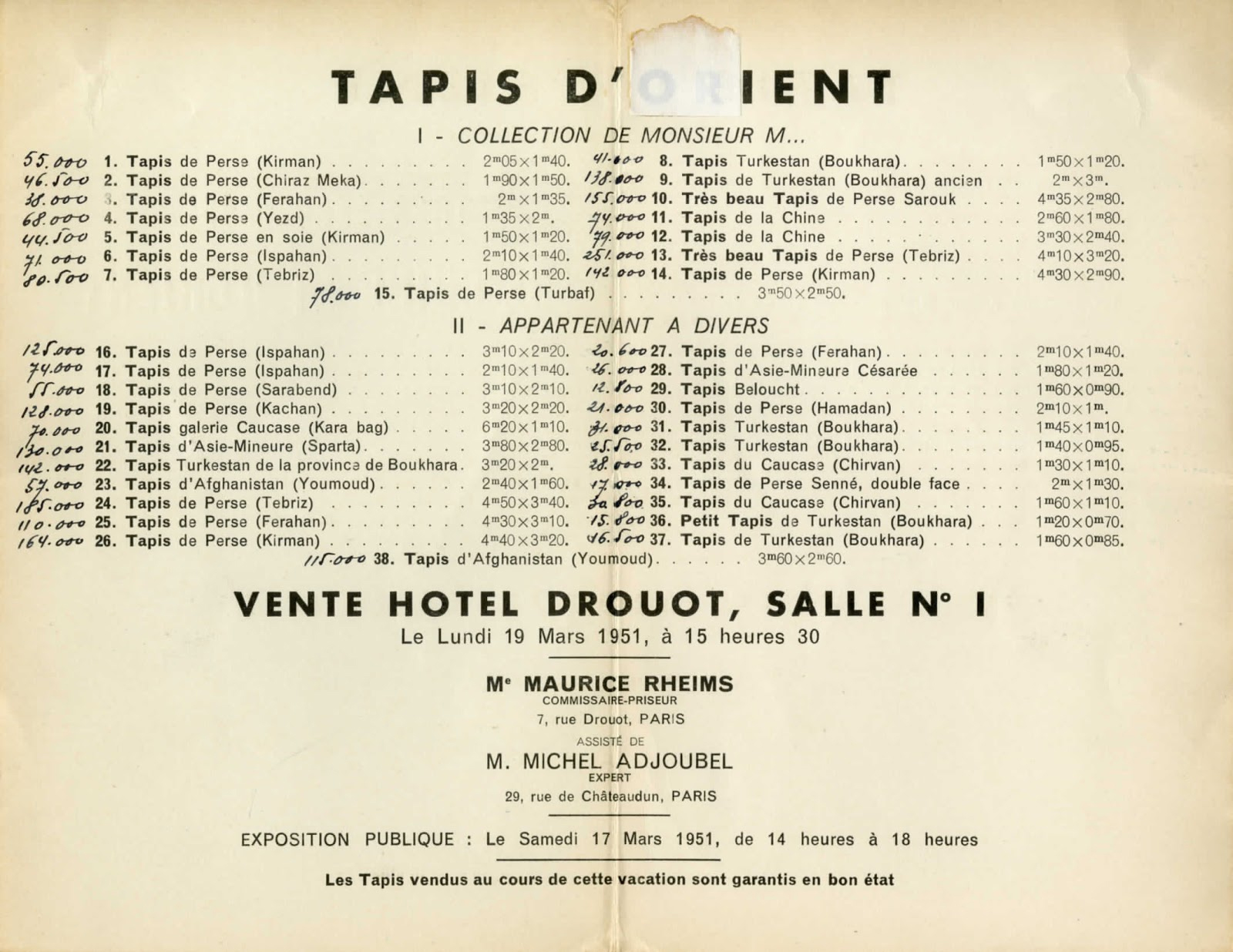

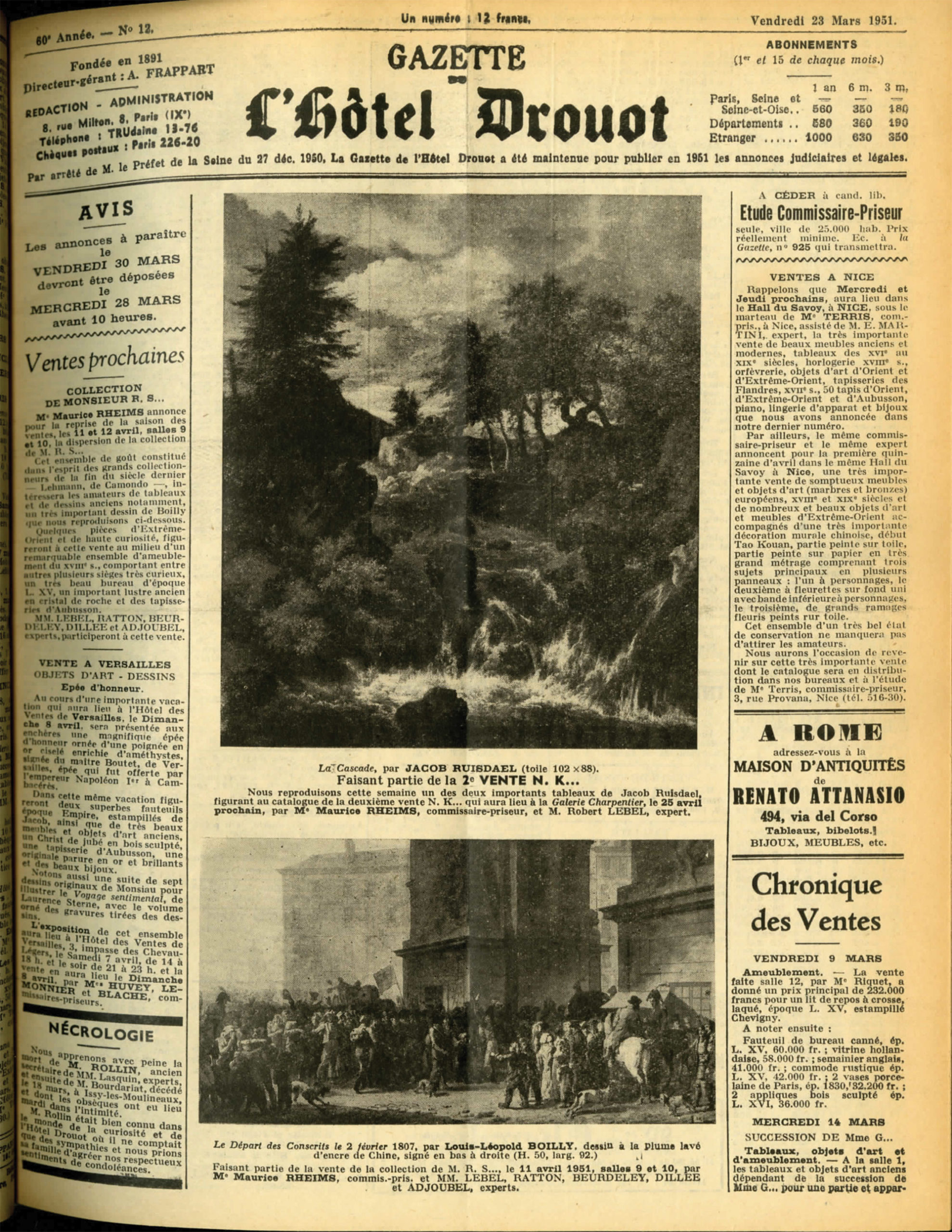

The ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ supposedly resurfaced at an auction held at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris by Maurice Rheims on 19 March 1951. Mr Ivanov duly supplies a copy of the catalogue entry. It is in English. Why would the catalogue for a French auction be printed in English?

- Fake Maurice Rheims catalogue

- Fake Maurice Rheims catalogue

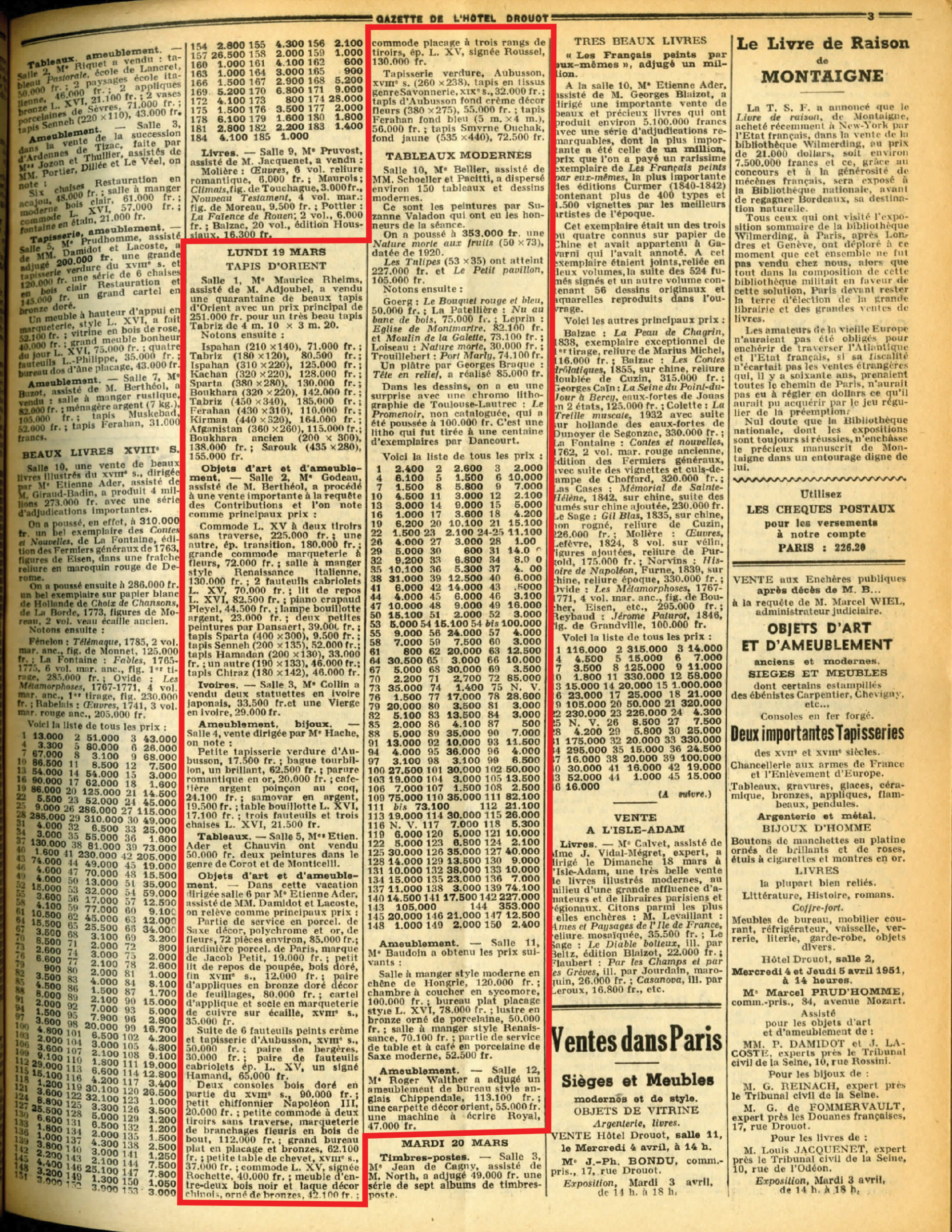

When I decided to check on the theme and contents of the auction, I discovered that the only auction held by Maurice Rheims on 19 March 1951 was devoted to ‘Tapis d’Orient’ (Oriental Carpets). I need hardly report that the sale did not include any Fabergé eggs. The Hôtel Drouot’s archives confirm that no ‘magnificent imperial Fabergé Easter egg’ was sold there in March 1951.

- Authentic Maurice Rheims catalogue

- Authentic Maurice Rheims catalogue

- Gazette de l’Hôtel Drouot, 23 March 1951

- Gazette de l’Hôtel Drouot, 23 March 1951

The provision of forged papers makes further discussion of the authenticity of this ‘imperial egg’ unnecessary. If anyone is still not convinced, I shall now advance further arguments.

DATE OF FABRICATION

The years 1904 and 1905 were two of the most dramatic in Russian history – those of the Russo-Japanese War (9 February 1904–5 September 1905) ending in a heavy Russian defeat. ‘Bloody Sunday’ took place on 22 January 1905. The subsequent ‘First Russian Revolution’ and wave of internal terror counted the Tsar’s uncle, Grand Duke Serge, among its victims.

Fabergé researchers, without exception, are unanimous in their opinion that the Empress and Dowager Empress were not presented with any traditional Easter gifts in 1904 or 1905. No invoice for Easter eggs dating from either year has been found in the archives. Fabergé’s chief workmaster Franz Bierbaum testified in his Memoirs that ‘during war years, eggs were either not made at all, or were of low cost and modest quality’ (The History of Fabergé – Memoirs of Franz Petrovich Bierbaum, St Petersburg 1993, p. 19). Fabergé’s invoices to the Tsar for purchases during these years reflect a striking reduction in imperial outlay, amounting to just 8,543 rubles during 1904 and 4,052 rubles in 1905 (Fabergé, Proler & Skurlov, op. cit., p. 59). Two de luxe Easter eggs do not fit into this dismal picture.

We also know that Fabergé was preparing another gift for Empress Alexandra for Easter 1904: the Moscow Kremlin Egg (now in the Kremlin Armoury). Work on this began after the imperial couple’s trip to Moscow during Easter 1903. The egg was due to be completed by Easter 1904 – ‘this date appeared twice – engraved and inscribed in white enamel’ – but was only presented to the Empress two years later, in 1906, as the archives confirm (cf T. Muntyan: Fabergé – Easter Gifts, Moscow 2018, pp 106-116).

One final point as regards date: the ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ was supposedly made to mark the tenth anniversary of the Nicholas/Alexandra marriage. But this took place in November 1894 – which would mean the gift supposedly commemorating it would have been presented six months too early. Given the customs and traditions of the times, and based on simple logic and the precedent of other gifts, it is impossible to imagine such a premature celebration.

STYLE & ICONOGRAPHY

Probably the most important feature of the Imperial Easter eggs is that each was unique. Their designs were never repeated, as Bierbaum stressed in his Memoirs: ‘in order not to repeat ourselves, we had to vary the eggs’ materials, appearance and contents’ (op. cit., p. 18). His assertion is not questioned by any Fabergé expert, and is confirmed by even a cursory analysis of items of reference in Russian and foreign collections.

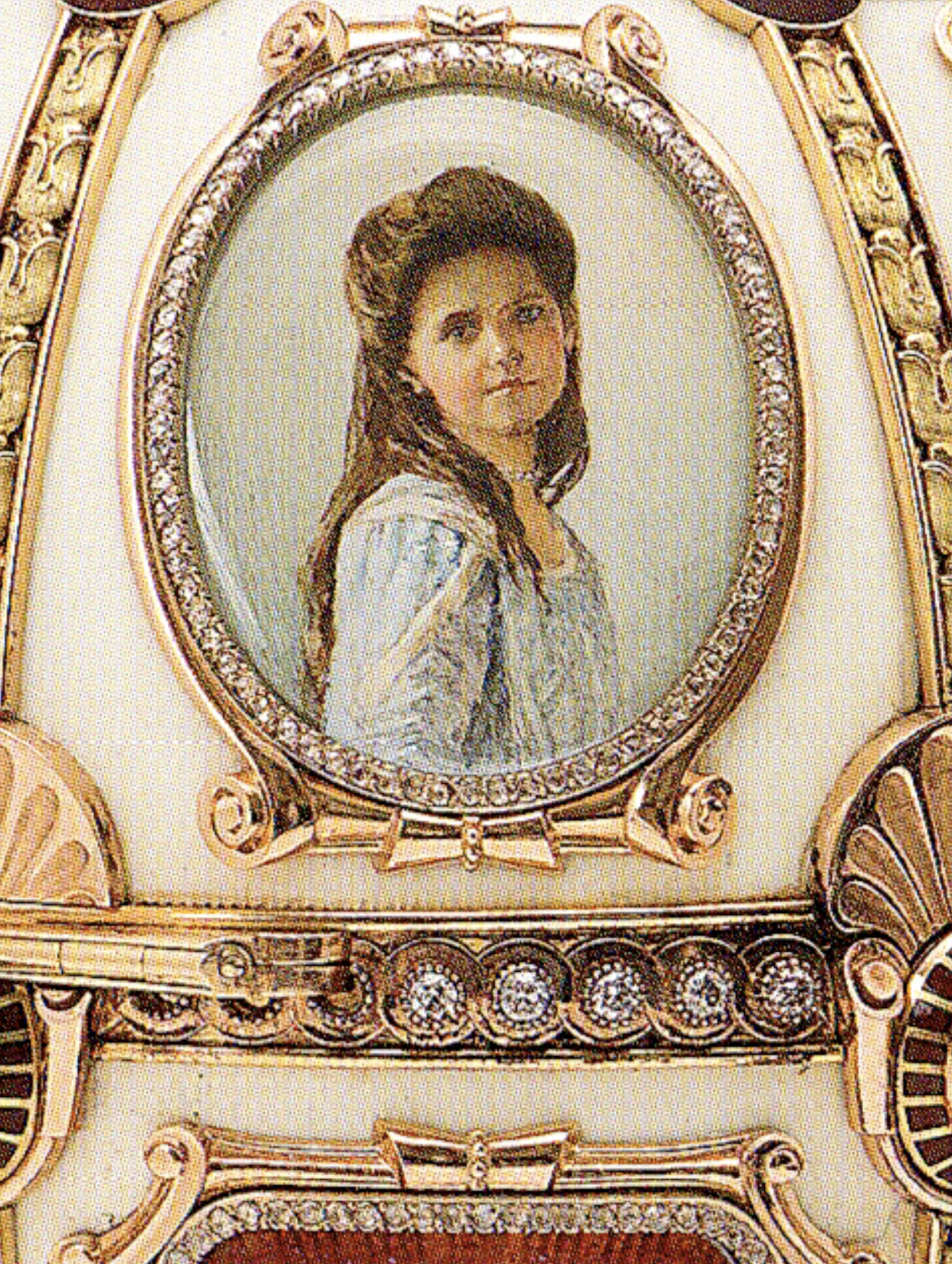

- ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ – exhibition catalogue, Fabergé – Jeweller to the Imperial Court

- Fifteenth Anniversary Egg (Fabergé Museum, St Petersburg)

When it comes to the ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ we are dealing with a pastiche composed of familiar elements. The basic design stems from the Fifteenth Anniversary Egg now in the Fabergé Museum in St Petersburg, whose exterior is divided into compartments containing miniature portraits of members of the imperial family. The egg from the Baden-Baden Museum offers only a slightly variation on this theme. The ‘surprise’ it contains – in the form of a bouquet of flowers – is a crude copy of the egg made for Empress Alexandra in 1901, now in the British royal collection (see above).

Basket Of Flowers Egg (The Royal Collection Trust)

Both its composition and quality of execution preclude any possibility of the ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ being an original work by Fabergé. The miniature portrait medallions bear no resemblance to those produced by Vasily Zuev, one of the most accomplished miniaturists of his time. Their stylistic mediocrity betrays their status as modern fakes.

The significant historical inconsistencies about the medallions affixed to ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ have been signalled by American researcher DeeAnn Hoff. As in the case of the Fifteenth Anniversary and Alexander Palace Eggs, Fabergé’s miniature portraits of the imperial family were based on contemporary photographs, which Hoff has located. Given the time that would have been needed to produce any egg presented for Easter 1904, such photographs must have been taken no later than 1903. Hoff’s research shows, however, that the Grand Duchess Olga medallion on the ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ is based on a photograph taken in 1904; the medallions of her sisters Tatyana and Anastasia are based on photographs taken in 1906; and the medallion of Grand Duchess Maria is based on a photograph taken in 1910. The posture, head position, hairstyle and clothing in the photos and miniatures are identical.

- Grand Duchess Olga – Boissonas & Eggler, St Petersburg 1904

- ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ (detail)

- Grand Duchess Maria – 1910

- ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ (detail)

The date discrepancy is especially noteworthy as regards the Tsar’s youngest daughter, Anastasia. She was born in 18 June 1901. In 1903, when work on the egg would have been carried out, she was just two years old. Yet her miniature on the ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ shows the portrait of a five-year-old girl.

Apparently, in an attempt to explain this obvious anachronism, Ivanov came up with the story of the original Blaznov miniatures being replaced by later works by Zuev. I have already shown that the documents supporting this assertion are fake. Even if we assumed for a moment that such a replacement did indeed take place, it would still not explain how a portrait from 1910 appeared among miniatures painted in 1908.

DeeAnn Hoff also draws attention to another important detail that cannot be explained by any theory to do with portrait replacement. The medallion portrait of Nicholas II on the ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ was based on a photograph taken back in the 1890s – between late 1892 and early 1896, going on the medals adorning the Tsar’s uniform. In addition, the ribbon of the Danish Order of the Danebrog (second decoration from the right) is painted blue, not white-and-red as it should have been. For a Fabergé imperial gift to contain such an aesthetic and diplomatic error is absolutely unthinkable.

Conclusion

The ‘Wedding Anniversary Egg’ is a modern fake. The is abundantly evident from both the ‘documents’ supplied by Mr Ivanov – whose inauthenticity can be easily verified by consulting the archives – and small individual details. This is evidenced first and foremost by the very execution of the object, its ‘handwriting.’ Items made by modern craftsmen are very different those made in the early 20th century, as are handwritten sources of the corresponding period. Fakes almost never succeed. This does not mean modern items are necessarily worse – they may sometimes be better and more skilfully executed. But they are never identical to antique objects, and the differences cannot escape the connoisseurial eye. The process of verification is both simple and difficult. It is simple because it does not require expensive instruments or in-depth scientific analysis but, at the same time, it is difficult because it requires particular skills that are not automatically acquired by working in a museum. Being a museum employee does not necessarily make you a specialist.

Andre Ruzhnikov

London

21 January 2021