Thanks to lockdowns, quarantines and coronavirus, the days of Russian Week parties, viewings, packed salerooms and posted catalogues are no more. On-line catalogues, as a result, need to be made more detailed to ensure potential customers have the very fullest information. The photography could certainly be enhanced, that’s for sure!

Christie’s lead off this month’s London auctions with a 270-lot sale on November 23. It starts with FINE ART and 35 lots by Maria Yakunchikova (1870-1902). Are there any Maria Yakunchikova collectors out there? Thirty-five lots by the same artist is a recipe for failure, even if there are a few decent-looking things among them.

Of the sale’s two Aivazovsky, I prefer his smaller and older Tempest painted in Osnova (near Kharkov) in 1855 (lot 38). I kinda like menacing, tempestuous Aivazovsky, showing the elements in brutal unstoppable fury – and this one’s a decent size (69 x 99 cm) and has a reasonable estimate (£250-350,000). His Genoese Towers by the Black Sea (lot 42) is later (1895) and quite larger (94 x 149 cm). It’s typical and nicely done, but the £700,000-900,000 estimate is probably a bit steep for a work painted five years before his death. Aivazovsky’s earlier works are of far higher quality.

Mikhail Nesterov, Sacred lake

Nesterov’s Sacred Lake (lot 39) is a good size and a great-looking picture – I love it. The estimate is a very modest £200,000-300,000. In the good old days a picture like this would have been priced on a totally different level. I do hope Christie’s did do all the due diligence. I dare say that this classic and very rare Nesterov (one of Russia’s greatest) is the best picture lot of the sale, never mind estimates. The same sleeping ever present Nude by Serebriakova that we’ve seen time and again whether tits up, down or to side with a low estimate of £400,000. or an early Konchalovsky at £300,000. make one think that COVID’s harsh presence does affect people’s thinking. I’d certainly put Nesterov way above the auction’s picture offering.

Nikolai Bogdanov-Belsky, The reading lesson

Then come a lacklustre bunch of makeweights: a Krachkovsky Tree in Blossom; a mundane Dubovskoi landscape; three lots of early 19th century drawings by Alexander Orlowski (est. £2,000-3,000); and a couple of tired, perfunctory Harlamoff kiddy sullen looking portraits with the same models that seem to appear in every sale. Seen one, you’ve seen them all. Lots 54 and 55 are typical child pictures by Bogdanov-Belski (estimates from £60,000 to £90,000). Again, almost every auction has one or two.

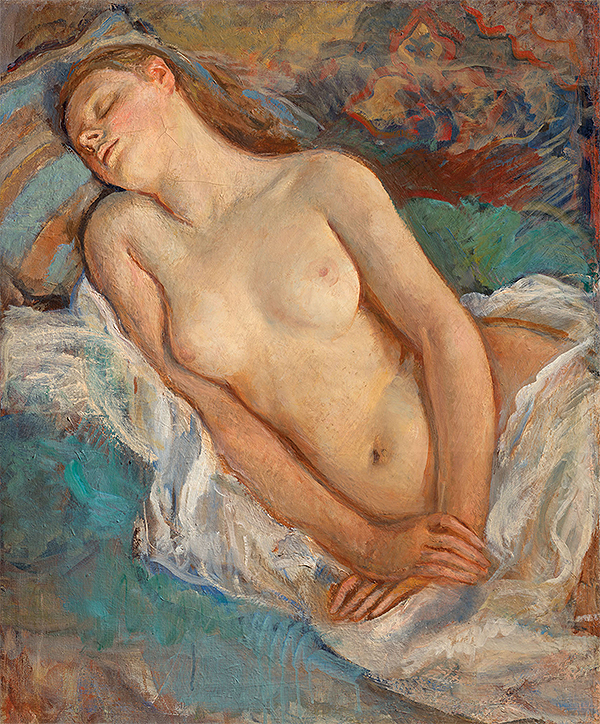

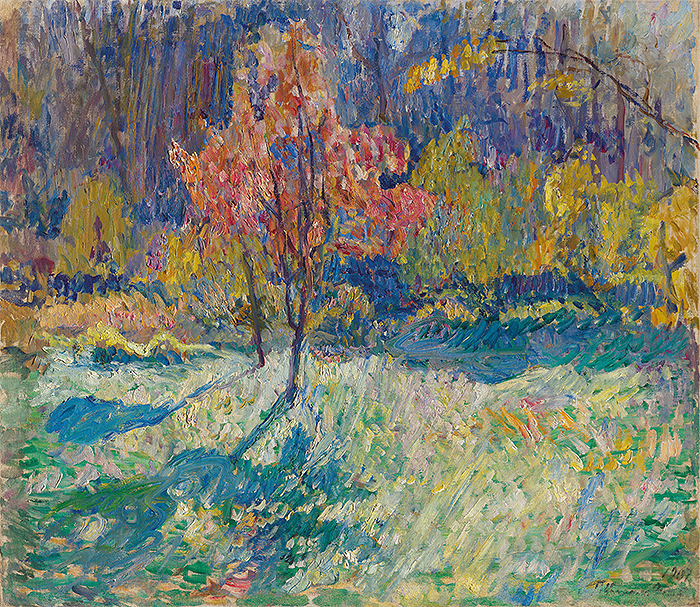

Petr Konchalovsky, Belkino. Small garden

After a decent, early Konchalovsky from 1907 (lot 61), showing the Garden on his Belkino estate south-west of Moscow (est. £300,000-500,000), comes a cheerful 1920s Korovin with a white-gowned woman on a garden bench (£200,000-300,000). Lot 63 is a Serebriakova Nude (c.1928) – one of her many naked depictions of her teenage daughter. Excuse me, but I can never understand a mother painting lascivious pictures of her own daughter! Serebriakova is a decent artist, but the estimate is a whacking £400,000-600,000. I just don’t get why Russians pay hundreds of thousands for such works! What’s the big deal?

- Zinaida Serebriakova, Nude

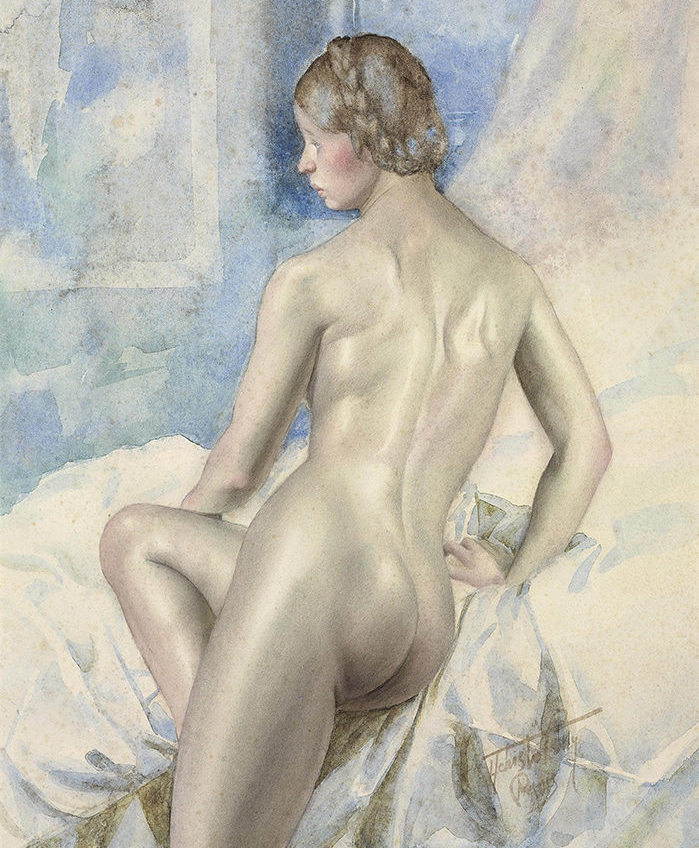

- Lev Tchistovsky, Nude with her head turned

Another Russian artist who moved to France, Lev Chistovsky (1902-69), also portrayed nothing but naked female bodies. Yet his works sell for lower five-figure numbers. Is Serebriakova really such a genius compared to Chistovsky?

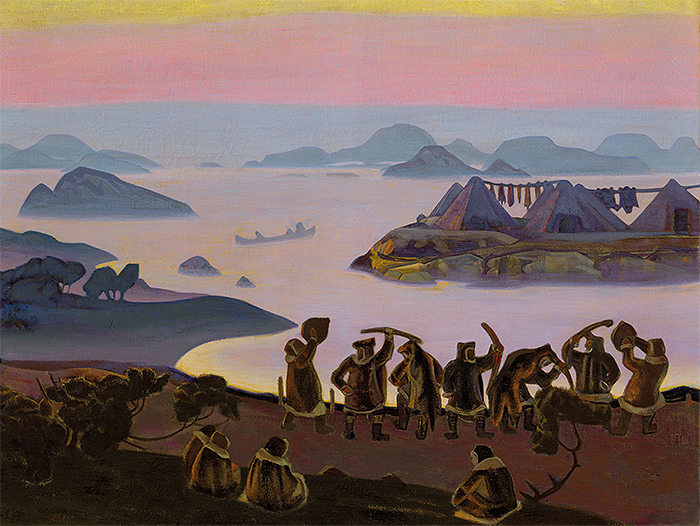

Nicholas Roerich, The Call of the Sun

Lot 70 is a very good, large, early Roerich that passed through my hands thirty years ago: The Call of the Sun (1919). Christie’s offered it unsuccessfully a year ago with an estimate of £1.5-2 million. The estimate is now down to £1-2-1.8m. It would have attracted more bidders a decade ago, alas these days ardent Roerich collectors are few and far between.

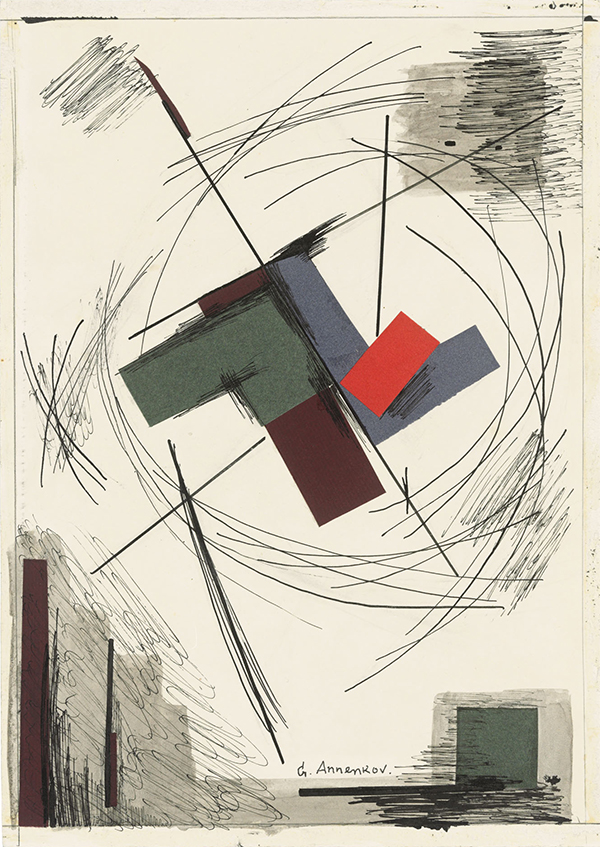

Yuri Annenkov, Two abstract compositions

The picture section ends with a bunch of second-rate, crummy Annenkovs. His Maison Hélie (a wine store in the Paris suburbs) comes with a crazy £80,000-120,000 estimate, followed by a French Marina touted at £15,000-20,000. Why such a difference? They’re both ugly. Four lots of Annenkov illustrations (lots 82-85) are just filler lots designed to get a few quid for the auction.

WORKS OF ART

Fabergé Guilloché Enamel Parcel-Gilt Silver Desk Clock

Fabergé items kick off the Works of Art section. Most are reasonably priced but nothing to write home about except for several gems. Several respectable lots include guilloché enamel desk-clocks by Wigström and Perchin. A £35,000-45,000 estimate is a bit high for a small light blue, entry-level clock like the Wigström (lot 132), but £60,000-90,000 estimates for the two Perchins (lots 134/135) reflect the current market.

Fabergé Jewelled and Guilloché Enamel Silver-Mounted Desk Clock

The stand-out clock is another Wigström job with beautiful, deep purple-coloured enamel in its original case. It’s in great condition and has a stellar imperial provenance – bought from Fabergé by Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna in February 1910. A fantastic piece! I wish I owned it myself (lot 137, est. £80,000-120,000).

- Jewelled Parcel-Gilt Silver Desk Clock

- Jewelled Parcel-Gilt Silver Desk Clock

Lot 138, a circular silver Desk Clock (est. £30-50,000), is just the opposite. I totally resent this assembly of bizarre elements being called Fabergé. That’s a travesty: it’s a piece of garbage. The back of the clock looks ridiculous – it must have been soldered into the rim, with rivets sticking out holding God knows what in place. The thick strut on the back does not have any of the marks you’d expect to see, and the engraved Moser & Co signature is less than convincing. The whole design is incongruous. Shame, shame, shame!!!!

Fabergé Gem-Set Silver-Mounted Rhodonite Desk Barometer

I reckon the fancy rim of this preposterous clock started out as the base of a pedestal of some sort, and was designed to be placed horizontally – like the Fabergé rhodonite desk barometer shaped like a ship’s capstan (below right) that Christie’s are offering as lot 133 (with an estimate of £8,000-12,000).

Christie’s admit that the scratched inventory number on the back of their circular clock is ‘indistinct.’ I’m surprised they didn’t get our old friend Valentin Skurlov to investigate. My efforts to persuade Christie’s distance themselves from their nebulous ‘Fabergé Research Consultant’ continue to meet the same glib, evasive response. ‘We’re looking into it’ they told me, when I went to King Street to look at the sale. ‘We just use him to identify inventory numbers and match them to invoices….’

I’ve no problem with that – but Skurlov continues to brandish his Christie’s title on his letterhead when peddling all kinds of nonsense. So, I’m thinking of sending the following letter to the overlord of Christie’s Russian Department, Alexis von Tiesenhausen:

Your Highness,

I came to Christie’s on 3 November 2020 and dispensed advice (albeit unpaid and unsolicited) regarding several pieces of Fabergé. May I therefore suppose that, like Valentin Skurlov, I can also call myself a Christie’s Consultant – and use this august title on my new letterhead? I will email the design for your blessing. As I’m sure you will agree, what’s sauce for the Skurlov goose is sauce for the Ruzhnikov gander. And, like Mr Skurlov, I’d love to cash in on my close relationship with Christie’s.

Looking forward to your tacit approval and benign indifference,

Yours etc.

- A Monumental and Very Rare Bronze Model of a Kirghiz With a Golden Eagle

- A Monumental and Very Rare Bronze Model of a Falconer

The sale’s otherwise lacklustre bronze section features two works (lots 141/142) of monstrous size and tremendous quality: a Falconer and Kirghiz with a Golden Eagle, each well over 6ft tall and beautifully cast as a pair by Fx Chopin Fabricant de Bronzes in St Petersburg in 1878, to the designs of Evgeny Lanceray. Both are valued at £100,000-150,000 – a steal. They’re the stars of the auction. Bronze aficionados should really push the boat out to get hold of them.

Frenchman Félix Chopin (1817-92) spent oven four decades as head of a foundry in St Petersburg, often working for the imperial court in collaboration with Lanceray. These two sculptures were consigned from South Africa – they had spent half a century at Rossmore Castle, near Monaghan in Ireland, before being shipped to Cape Town after World War II. According to Christie’s only three other pairs were cast: one for Nicholas I’s granddaughter Queen Olga of Greece (to embellish her summer palace at Tatoi just outside Athens); another now grace the promenade in Menton on the Riviera; a third were moved to Baku in 1926 and now belong to the National Art Museum of Azerbaijan.

Diamond and enamel Fabergé brooches

From the sale’s largest items to the smallest: three cute, diamond and enamel Fabergé brooches (lots 160-162) with giveaway estimates of £2,000-3,000 that mark them down as potential sleepers. I think that pricing stuff below market is misleading. Auctions MUST estimate consignments based on the true current value and not because they have ensnared an estate thru some village lawyers who cares less as to the interests of their uninformed clients.

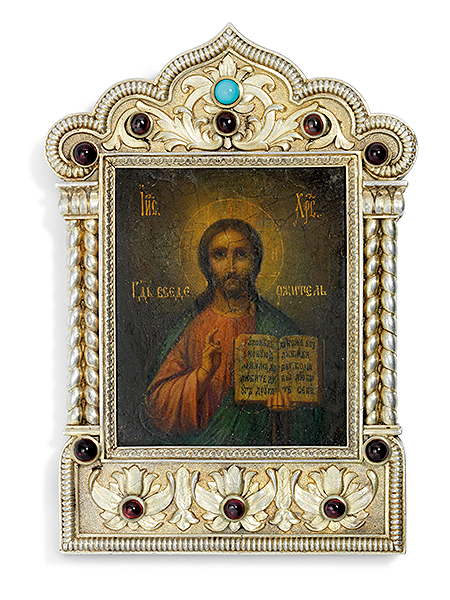

Fabergé Gem-Set Silver-Gilt Icon of Christ Pantocrator

A gem-set silver-gilt Fabergé icon with the mark of Karl Armfelt (1904-08) of Christ Pantocrator comes with a reasonable estimate of £10,000-15,000 (lot 175), while pick of the enamel section is a sublime-looking box made in Moscow (1908-17) by Feodor Rückert, whose Cyrillic mark Ф.Р. is over-stamped by the mark of Fabergé (lot 190). The lid features one of the most celebrated views in Russia: the Kremlin from the River Moscova with its green spires, white towers and gleaming domes surging skywards behind ochre-red, battlemented walls. The £150,000-200,000 estimate may sound a bit on the high side but the item is worth every penny of the low-estimate at least, and I can’t imagine it won’t sell. Pieces as good as this appear on the market once in a blue moon.

Three silver-gilt 18th century Moscow kovches (lots 183,184 & 262), with estimates in the £15,000-30,000 range, emerge from a morass of boring silver. But why is there an eighty-lot gap between them? It’s bad enough not having a proper paper catalogue without having to scroll up and down the on-line version due to thoughtless presentation.

I predict that two silver and niello Moscow snuff-boxes (lot 255), dating from around 1830, will get nowhere near their £4,000-6,000 estimate. These items are not in the least rare and, in fact, routinely sell for a mere £300-400. apiece. But I like the look of two early 19th silver and niello cartographic boxes (lots 263/264) with the mark of Feodor Bushkovsky from Veliky Ustyug – an ancient town near the confluence of the Yug and Sukhona rivers, halfway between Archangelsk and Vologda.

One box is rectangular, dated 1822, and has a panoramic view of Veliky Ustyug from across the River Sukhona (est. £8,000-12,000). The second box is circular, dated 1828, and has detachable cover with a map of the surrounding Vologda region (est. £10,000-15,000).

The name Veliky Ustyug won’t mean much to most Englishmen, even though the London tradesman Anthony Jenkinson recorded his stay in ‘Ustyug, an ancient town’ on 31 August 1557, en route to Moscow from the White Sea. Local boats were ‘very long and broad, and flat-bottomed, and draw not above four feet of water, and will carry 200 tons’ of merchandise at a time’ he reported conscientiously.

There’s the usual supply of Imperial Porcelain, including ten handsome but unremarkable 19th century military plates from the reigns of different Tsars, valued at between £10,000-30,000 apiece. Will the supply of these plates ever dry up? Every sale at Christie’s and Sotheby’s for the past 40 odd years has had a whole panoply of them! Does anybody know how many of the damn things were produced?

The sale concludes with a typical group of Soviet Propaganda plates that seem to keep racing along, Covid or no Covid.

FAIR GAME?

A Large Silver Wine Ewer in the Form of a Pheasant

A special mention for Lot 126: a silver wine-ewer in the form of a Pheasant – 66 cm long, height not given (I reckon about 45 cm). It comes with a very hefty estimate of £100,000-150,000, as Christie’s assign it to Fabergé with a confidence I vociferously challenge.

This Pheasant does look pretty German, or at least Western European, as far as I’m concerned. Some experts disagree but offer no further insight. The provenance is wishy-washy – ‘acquired by the grandfather of the present owner in Russia circa 1900’ write Christie’s. That’s just hearsay: Christie’s provide nothing in the way of receipts or documentary proof. They also signal the presence of ‘Swedish import marks.’ That means nothing as far as Fabergé’s authorship is concerned – it just means that, at some stage in its history, the Pheasant fluttered across the Swedish border.

The silver bird is supposed to be used for serving wine from its gilt interior – but it’s over 2ft long and weighs 2.5 kilos when empty… so just imagine trying to lift it with a couple of litres of Le Vin de Merde sloshing around inside. I bet most of it would get spilt over the tablecloth! I certainly wouldn’t consider pouring my guests any vintage claret or Romanée-Conti from this glorified watering-can.

- A Large Silver Wine Ewer in the Form of a Pheasant

- Le Vin de Merde

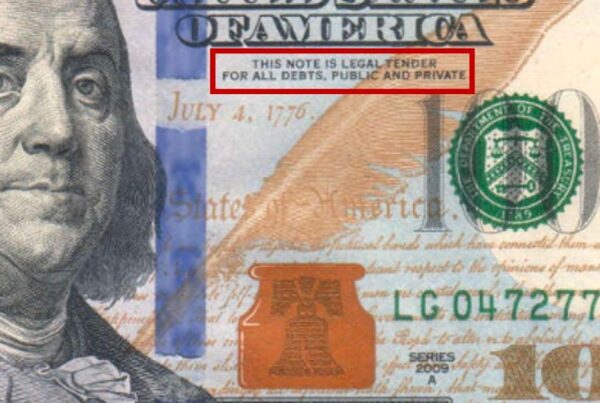

But what irks me most are the hallmarks. Although Christie’s declare the Pheasant is by Faberge and it is hallmarked to its head, neck and feet, they only provide a photo of the puny hallmarks placed on the head and neck, either side of the hinged opening. These double marks purposelessly replicate one another.

A Large Silver Wine Ewer in the Form of a Pheasant (Hallmarks)

I certainly would not expect to see hallmarks smack in the middle of the bird. These marks are virtually next to each other and are also very, very small. The bird is huge. The marks should be a lot bigger. There is ample space for them on or under the feet.

Fabergé marks don’t need to be ‘in yer face.’ They were seldom applied to the most visible parts of an object, for an obvious reason: to avoid impairing the item’s pristine appearance. I would expect a huge piece like this Pheasant to have a large Cyrillic ФАБЕРЖЕ (Fabergé) marked in full under the tail or – like Lot 110 (a Fabergé silver table-lighter in the form of a Chimpanzee) – on the bottom. Fabergé silver animals are typically hallmarked on the bottom, like the Smoking Monkey and Elephant table-lighter (not in the sale) shown below.

- Fabergé Smoking Monkey

- Fabergé Table-Lighter in the Form of an Elephant

Workmaster Julius Rappoport created most of Fabergé’s animal figures from 1890 onwards. Christie’s declare that Empress Maria Feodorovna purchased a silver pheasant from Fabergé in 1893, and that Grand Duke Vladimir’s 1917 inventory records a silver pheasant and a capercaillie. Great news!!! Yet Christie’s offer no supporting evidence for these throwaway claims: no photographs, no inventory numbers, no dimensions…. How big were these supposedly Romanov-owned pieces? Around 4 inches (9-12 cm) long, like most Fabergé animals? And what was their pose or purpose?

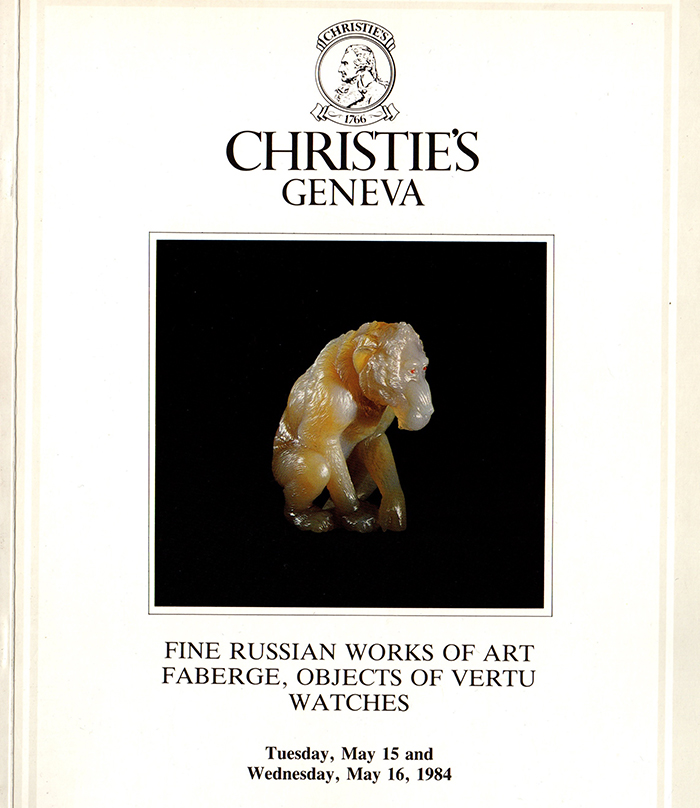

- Christie’s Geneva Catalogue, May, 1984

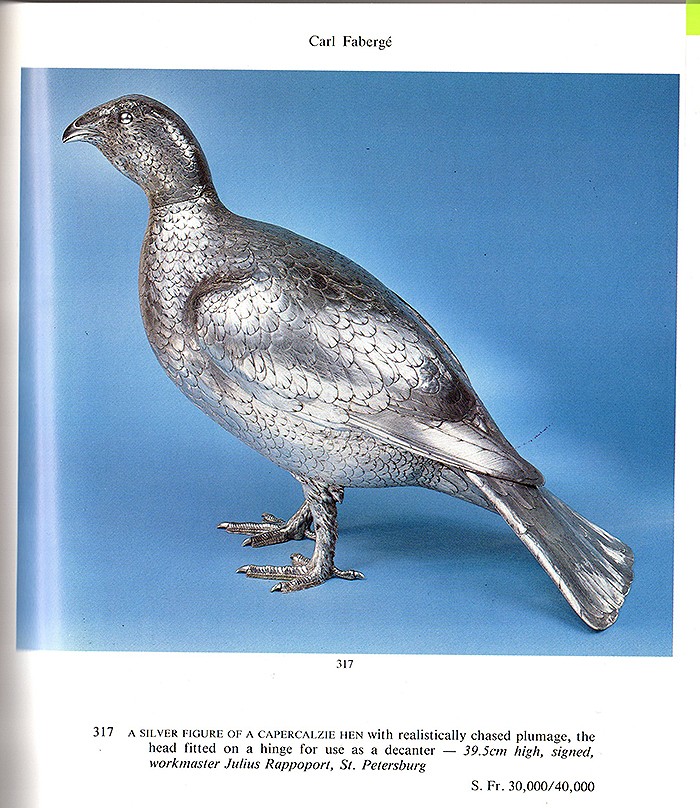

- A figure of Capercaillie, Christie’s Geneva Catalogue, May, 1984

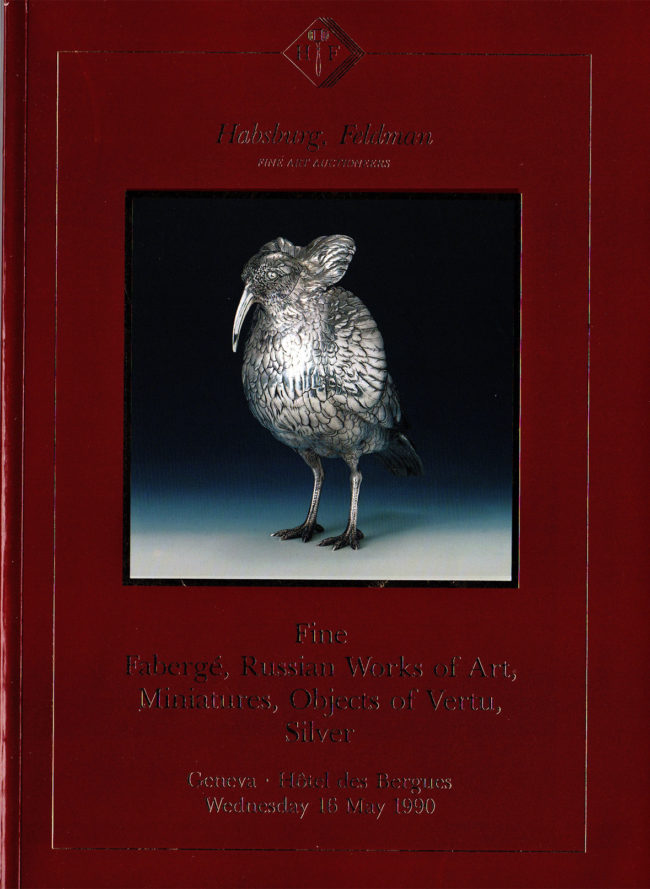

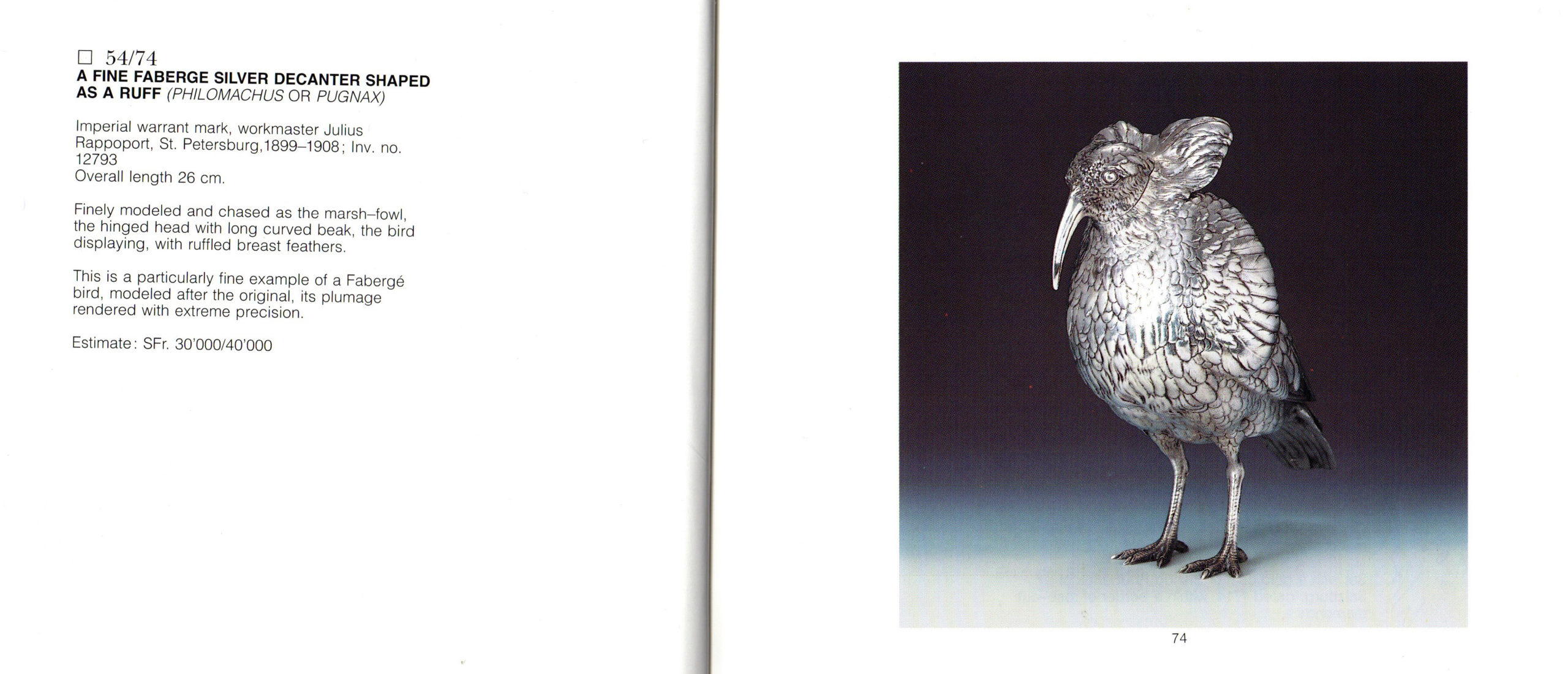

A Ruff supposedly by Rappoport was bought for CHF 42,000 at Habsburg-Feldman in Geneva in May 1990 – reportedly by a well known London dealer who sold it to America. Christie’s also cite a game bird supposedly by Rappoport, termed a Capercaillie (though some might call it a Grouse), offered at Christie’s Geneva in May 1984.

Habsburg-Feldman Geneva Catalogue, May, 1990

A Figure of Ruff, Habsburg-Feldman Geneva Catalogue, May, 1990

It would have been great to compare our lumbering Pheasant with this famous Grouse or Capercaillie (Christie’s Geneva in May 1984) and Habsburg-Feldman’s Ruff. These spurious references to auctions held over thirty years ago are meant, of course, to convince would-be buyers that the 2020 Pheasant is beyond suspicion. They achieve nothing of the sort. Thanks to demise of the Soviet Union a stream of books, exhibition and scholarly articles has appeared and now we know infinitely more in 2020 about Fabergé and his legacy than we did in the 1980s.

Both Christie’s and Habsburg-Feldman’s Grouse and Ruff mention an IP hallmark for Rappoport. But neither catalogue describes or shows the hallmarks (or inventory numbers) and, despite their being sold in Geneva Russian auctions, I would stridently dispute their birth at Fabergé workshops. They appear similar in quality to the very questionable 2020 Pheasant or other birds of the same German feather.

London antique shops are brimming with game birds, big, medium, small – all are very popular among hunters and similar in appearance. But I don’t know any Fabergé birds the size of Christie’s humongous Pheasant, no such creatures appear in multitude of books and exhibition catalogues on the revered master either. This brazen attribution, supported by no hard-and-fast evidence whatsoever, displays wanton disregard for scholarship and art historical truth.

I spoke about this birdy to several of my learned colleagues endowed with years of experience and knowledge, all are unanimous in sharing my utter skepticism. Any expert erred in the past, but such an egregious misattribution by a leading auction house is simply ludicrous.

Do not forget the silver capstan clock described above either!!! Remember, it does belong in a garbage bin.