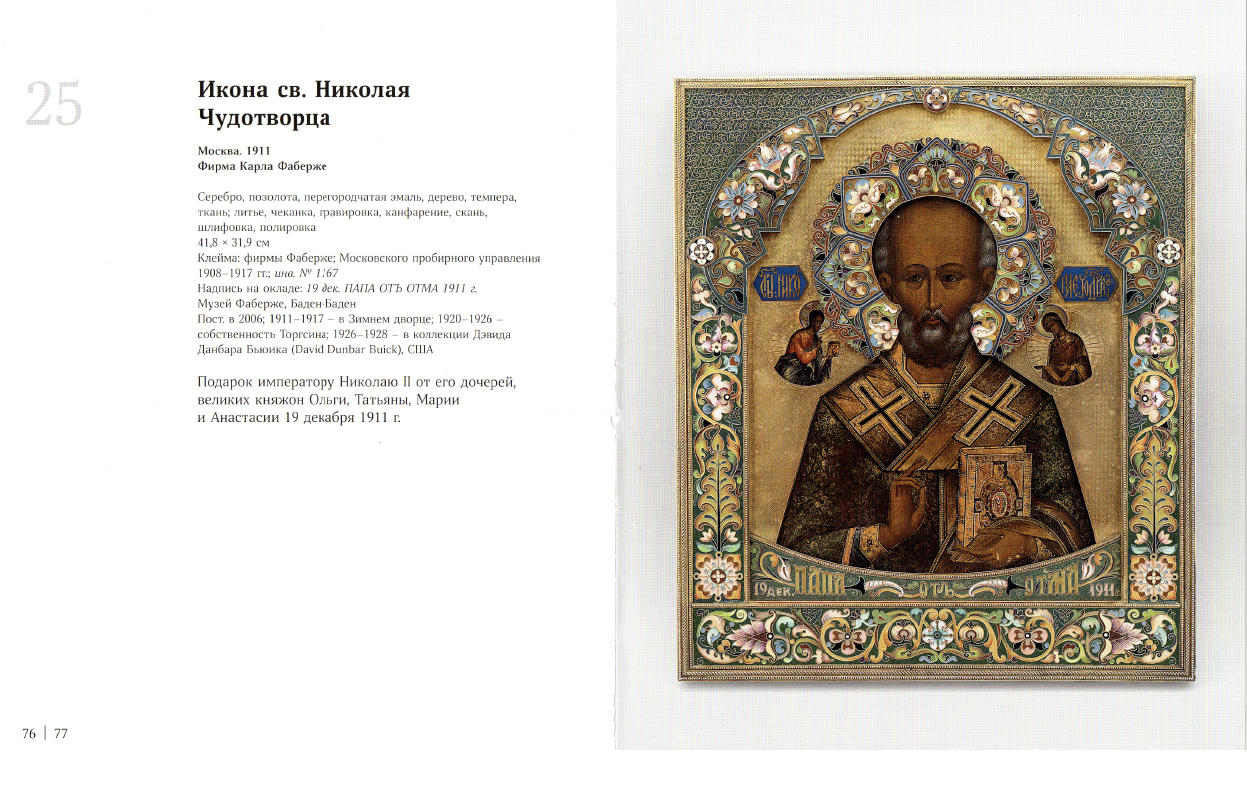

Professor Ivanov has complained, in one of his speeches, about my ignoring the icon of St Nicholas the Wonderworker (n° 25 in the Hermitage catalogue) when discussing Fabergé fakes. I’d like to correct this unfortunate oversight right now.

‘Fabergé – Jeweller to the Imperial Court’ Exhibition Catalogue

Contrary to what Prof. Ivanov may think, I have no complaints about the image of St Nicholas itself: in all likelihood it’s a genuine (though probably restored) 19th century work. It’s not the Saint who worries me, but his elaborate enamel oklad (cover) – which I shall now discuss in some detail.

According to the catalogue, this oklad was made by Fabergé’s Moscow workshop between 1908 and 1917. It bears a dedication dated 1911.

Prof. Ivanov and Mr Piotrovsky, the gentleman who looks after his interests, have repeatedly emphasized the non-commercial nature of their Hermitage exhibition. Prof. Ivanov has said many times that his collection, due to its exceptional cultural significance, is not for sale. This is not strictly true. I am aware of various attempts by the Professor to sell some of his pieces – including the icon of St Nicholas the Wonderworker (which, according to the Hermitage catalogue, has been in the Fabergé Museum in Baden-Baden since 2006). In 2018 Prof. Ivanov wanted to enter the icon with Paris auction firm Leclere, with an ambitious reserve-price of €500,000. Before accepting such a precious lot, the sale expert sought the opinion of Fabergé specialists, including the well-known authority Alexander von Solodkov, author of numerous academic publications. I also became acquainted with the item before it was included in the catalogue.

Both of us swiftly and independently concluded as to what Mr Piotrovsky might call the ‘inauthenticity’ of the piece. To put it more bluntly, using professional jargon: we thought it was a shameless, low-level fake. The icon did not make it to auction.

Our conclusion was based on a number of factors broaching no argument – starting with how different this oklad looks from those made by Fabergé. The oklad’s halo and arched frame are decorated with stylized flowers, with filigree work in the top corners; the combination of colour, patterning and composition is far from what Fabergé were doing from 1908 to 1917. There may be similarities with items made in other Moscow workshops, but this particular oklad has nothing to do with anything produced by Fabergé at that time. From 1908 onwards, the objects with cloisonné enamel produced in Fabergé’s Moscow workshops had a distinctive, highly recognizable appearance.

The main features of this style were quasi-abstract ornament, echoing designs produced at Abramtsevo and Talashkino; and a colour-range generally restricted to cool blue, marsh green, ash grey and shades of brown, set off by dashes of red and orange. The ornament’s graphic nature was emphasized by the outlines of the cloisonné, combined with criss-cross patterns from the amalgam. Works in this style are associated with the enamel specialist Feodor Rückert, who worked for Fabergé in Moscow (for more details on Rückert’s work see Tatiana Muntyan’s catalogue to the recent exhibition in the Moscow Kremlin: Carl Fabergé and Feodor Rückert – Masterpieces of Russian Enamel, Moscow 2020).

- Prince Vladimir Icon – Fabergé (1908-17), workmaster F. Rückert (Fabergé Museum, St Petersburg)

- Hodigitria Mother of God Icon – Fabergé (1908-17), workmaster F. Rückert (Private Collection, sold at Christie’s London 3 June 2013, lot 286)

A striking example of such work is the oklad of a St Vladimir icon that passed through my hands in the mid-1980s, and is now in the St Petersburg Fabergé Museum (cf Fabergé: Treasures of Imperial Russia – St Petersburg 2017, p. 272). Another example is the Hodigitria Mother of God sold at Christie’s London on 3 June 2013 (lot 286). Other items produced by Fabergé in Moscow during the period were decorated in similar style.

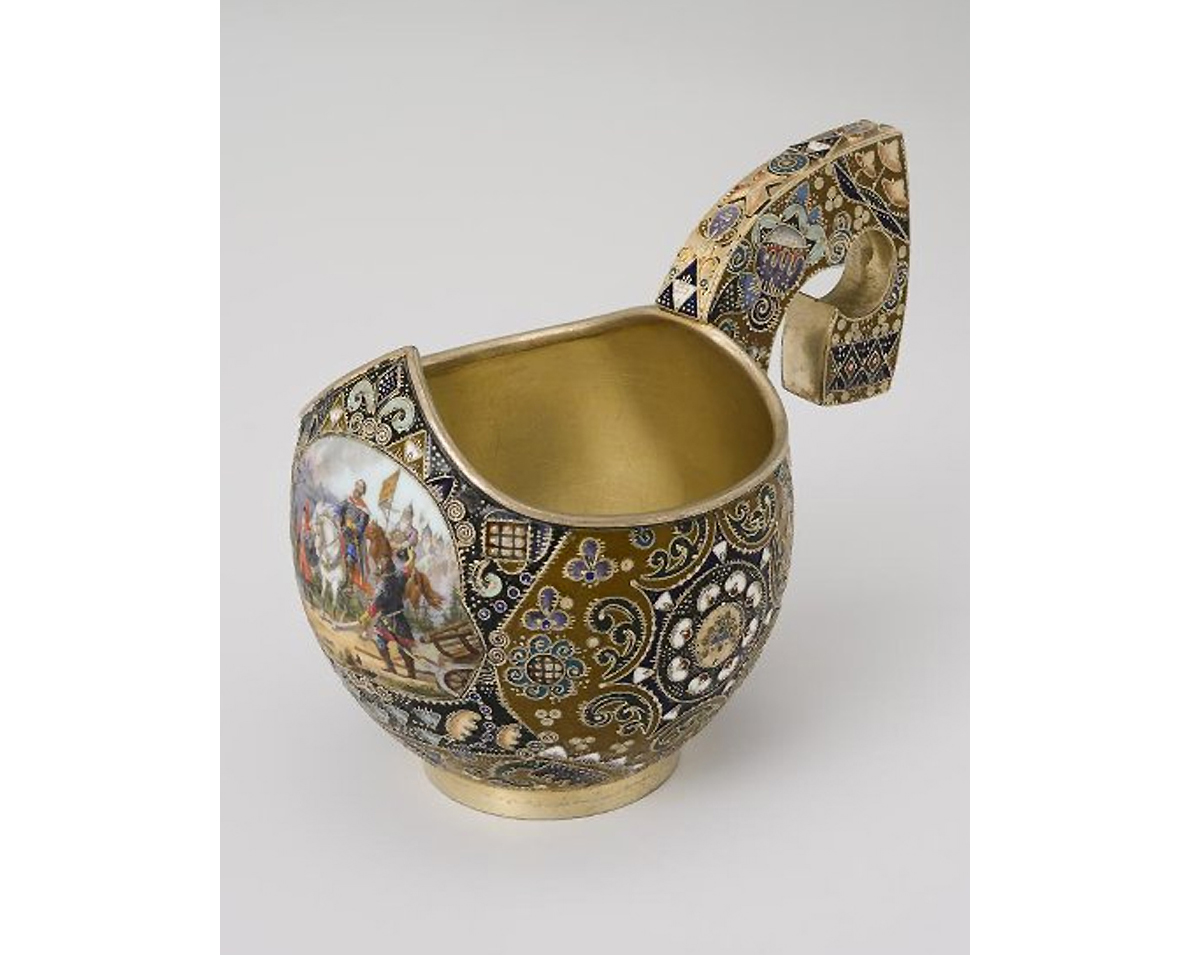

- Kovsh – Fabergé (1908-17), workmaster F. Rückert (Moscow Kremlin Museums)

- Box – Fabergé (1908-17), workmaster F. Rückert (Fabergé Museum, St Petersburg)

Examples include a kovsh with a miniature based on Boris Zvorykin’s painting of Prince Pozharsky at the Battle of Moscow (Moscow Kremlin Museums, Inv. No MR -11521 / T. Muntyan: Works by Leading 19th & Early 20th Century Jewellery Firms – The Firm of C. Fabergé, Moscow 2019, pp 273/4, n° 122); a box with a miniature based on Konstantin Makovsky’s Bandura Player (St Petersburg Fabergé Museum; Fabergé – Treasures of Imperial Russia, p. 261); a cigarette case with a miniature of Viktor Vasnetsov’s Knight at the Crossroads (ibid, p. 263); and many other items in private and museum collections.

- Cigarette Case – Fabergé (1908-17), workmaster F. Rückert (Fabergé Museum, St Petersburg)

- Cigarette Case – Fabergé (1908-17), workmaster F. Rückert (Fabergé Museum, St Petersburg)

Apart from obvious stylistic differences, the forger’s hand is also revealed by the hallmarks.

St Nicholas the Wonderworker fake hallmarks (Fabergé Museum in Baden-Baden)

The oklad features a FABERGE hallmark; a large, smudgy, double-headed eagle emblem; and the hallmark of the Moscow Region Assay Office in the form of a female head in a kokoshnik facing the number 88 (indicating silver purity) to her right. These hallmarks are loaded with errors. Instead of the K.FABERGE hallmark used by the firm’s Moscow branch, the forger used their St Petersburg hallmark (which had no initial). The eagle emblem is too big and carelessly applied, with the firm’s name and emblem embossed separately instead of together. The oval surrounding the assay hallmark is blurred, poorly defined and distorted, and the assay mark itself is missing the Greek letter used to indicate the region – Δ (delta) in Moscow’s case.

- Kovsh hallmarks (Moscow Kremlin Museums)

- Cigarette Case hallmarks (Fabergé Museum, St Petersburg)

Another problem is the lack of homogeneity between the icon and its oklad. Although embedded beneath a precious oklad from 1911, the icon itself dates from the mid-19th century and, stylistically, is far simpler. A special reason – great age or artistic merit – was required for an image to receive an oklad not made at the same time. Neither of those factors applies here.

As usual, Prof. Ivanov does not stop at attributing another fake to Fabergé – he has also come up with a fictitious Imperial provenance. Relatively few icons with a Fabergé oklad were ordered for the Imperial household: between 1900 and 1914, for instance, just 18 such items are listed by Valentin Skurlov (see his blog dated 17 January 2009), with only 11 of them actually delivered. An oklad for an icon of St Nicholas was not among them.

We are asked to believe that the icon was an Imperial gift not only because of ‘documents’ of unknown origin, but also because the dedication near the bottom of the oklad suggests the icon was presented to the Tsar by his daughters on St Nicholas Day, 1911.

First of all, it is hard to believe such a gift could have been offered to the Tsar without the participation of his only son and heir, Alexei.

Secondly, the dedication is utterly implausible. It is signed OTMA, a name formed by the initial letters of the Grand Duchesses’ first names (Olga-Tatiana-Maria-Anastasia). Their tutor Pierre Gilliard, in Treize Années à la Cour de Russie (first published in 1921, and translated into English as Thirteen Years at the Russian Court), reported that ‘with the initials of their Christian names they had formed a composite Christian name, OTMA, and under this common signature they frequently gave their presents or sent letters written by one of them on behalf of all.’ No letters or presents signed in this way have ever come to light. The only document known to feature this signature is a poem called K OTMA (‘to OTMA’) by another Imperial tutor, Piotr Petrov (cf E.A. Chirkov: Documents in the State Archives about the Family of Tsar Nicholas II / Children’s Section – Childhood in the Tsar’s Home, OTMA and Alexey, Moscow 2000, p. 77).

Then there’s provenance. Not only is there no archival support for an Imperial – a string of embarrassing historical errors confirm it as fake:

1) The Hermitage catalogue states that the icon was in the Winter Palace from 1911 until 1917. Yet the Imperial family had abandoned St Petersburg after the revolutionary events of 1905 and gone to live in Tsarskoye Selo, whose Alexander Palace would remain their principal residence for the next twelve years. The rooms of both the Winter Palace and the Alexander Palace are familiar to us through photographs – many of which clearly show personal belongings. It is most bizarre that no such icon can be seen in any of these photographs.

2) The catalogue asserts that the icon was in the possession of Torgsin (the All-Union Association for Trading with Foreigners) from 1920-26. That is unthinkable: Torgsin was only created in July 1930.

3) The icon’s next supposed owner, from 1926-28, is listed as American industrialist David Dunbar Buick (1854-1929), founder of the Buick Motor Company. I first learned that Mr Buick was a Fabergé fan when I read the Hermitage catalogue. During my fifty-year career, spent mostly in the United States, I had never heard of any Buick Collection – though I’m happy to put that down to lack of erudition. Mr Buick’s love of Fabergé is less suspicious than the absence of any documents confirming such a provenance.

The Hermitage catalogue actually contains four items from the Buick Collection (nos 7, 11 & 82, in addition to the icon). How and from whom did Prof. Ivanov acquire these pieces? Had they been owned by the same owner all these years? If not, it must have taken an incredible stroke of luck for the Professor to re-unite items from a collection that was apparently dispersed in 1928. This luck seems to have apply to almost all of the items dispalyed at the Hermitage. According to Ivanov, they all come from a handful of (principally American) private collections. How were these collections re-united? Why had they never been heard of before? Why had none of these items ever been published or exhibited? The questions are many; the answers, sadly, non-existent.

All of which allows us to definitively conclude that the Wonderworker’s oklad has nothing to do with Fabergé and is a modern fake – made by someone with a very limited grasp of the firm’s output, and unable to convincingly imitate their style. If the academic training of the Hermitage employees responsible for storing and studying Fabergé’s works does not allow them to spot a blatant forgery when it’s staring them in the face, I suggest they carry out the sort of technological assessment Mikhail Piotrovsky keeps talking about. I hope, however, that such expensive research will be paid for by the owner of this ‘masterpiece,’ and not out of Museum funds – which, in my humble opinion, could be more usefully assigned to hiring a knowledgeable specialist to fill the vacant post of Fabergé Curator.

*

On 17 September 2020 the wonderworking Ivanov icon was blessed during a Fabergé memorial service at the Russian Orthodox church in Wiesbaden. This was a stomach-churning stunt, even by the Herr Doktor Professor’s cheap moral standards: a fake Fabergé oklad, with the bogus signature of the Tsar’s martyred daughters, receiving kisses of holy approval from dignitaries from the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. At a ceremony ostensibly commemorating the 100th anniversary of Carl Fabergé’s death.

Just 100 miles south of Wiesbaden lies Baden-Baden: another German spa town with a Russian Orthodox church, where Prof. Ivanov’s ‘Fabergé Museum’ opened next to a Thai massage parlour in 2009. The Professor claims to have spent €17m renovating his 19th century Baden-Baden town-house, so we’d expect gold handles, malachite floors and beautifully illuminated vitrines to show off a precious collection with a sticker price of two billion dollars. No chance! Only three rooms appear to have been renovated: one is filled incongruously with pieces of supposed Pre-Columbian gold; another – business is business – houses the museum shop, brimming with cheap trinkets; the third has been turned into a pokey little café with a plasma TV screen and plastic orange seating. The menu matches the opulence of the interior. Luckily, on sunny days, you can escape the smell of putrid borsch wafting in from the kitchen by heading outside to the patio with its giant kitschy Rabbit by Zurab Tsereteli (‘it is a tradition to have your photo taken with our rabbit’ the website warns visitors).

Patio of Fabergé Museum in Baden-Baden

The museum’s pokey little website proclaims misleadingly that ‘We have open (sic) since May 30, 2020’ (they are currently closed due to Covid) – pursuing its professorial English with (among other gems) hight for height, bowenit for bowenite, Franch for French and Empresses Eugénie for Empress Eugénie.

The website of the Baden-Baden Tourist Office is equally reliable, insisting this is ‘the only museum in the world dedicated to Fabergé.’ Tourists seem sadly unimpressed. Although – insists the Professor – an Arab Sheikh once offered to buy his fake-spangled collection for $2 billion, his museum ranks just 20th of Things To Do in little Baden-Baden (population 50,000), according to TripAdvisor.

You need a sheikh’s income to visit, in any case: at €18, entry costs 20% more than the Louvre, and three times more than the world’s only other museum dedicated to Fabergé, with its sparkling collection of Imperial Easter Eggs, in a grandiose 18th century place, in stately St Petersburg.

The Prof. must need the dough – forgeries don’t come cheap, and not even St Alexander Ivanov can work miracles every day.