It was gratifying to learn that, after all the rage and denial, the Hermitage finally accepted to dispatch the most toxic exhibits from its current ‘Fabergé’ show for belated analysis. The initiative is welcome, though it is not entirely clear to what kind of analysis Mikhail Piotrovsky and his team wish to submit, say, the bevy of 19th century tiaras grotesquely attributed to Fabergé. Be that as it may… I, along with all the connoisseurs and professionals monitoring this affair, expect these studies to be carried out transparently – with the results published and made available for review. After all, as Mr Piotrovsky has rightly noted, this is not a market dispute but an academic one: we are not talking about what this distinguished museum director has decided to put on his mantelpiece, but inside the display-cabinets of the country’s leading cultural institution.

While the Hermitage laboratories proceed with their work, I shall continue with mine. There are, as Mr Piotrovsky has correctly noted, ‘three ways to address questions [of authenticity] – via technical aspects, documentation, and art historical analysis placed in context.’ Let’s apply this happy formula to one Hermitage exhibit in particular: its much-touted Soldier figurine.

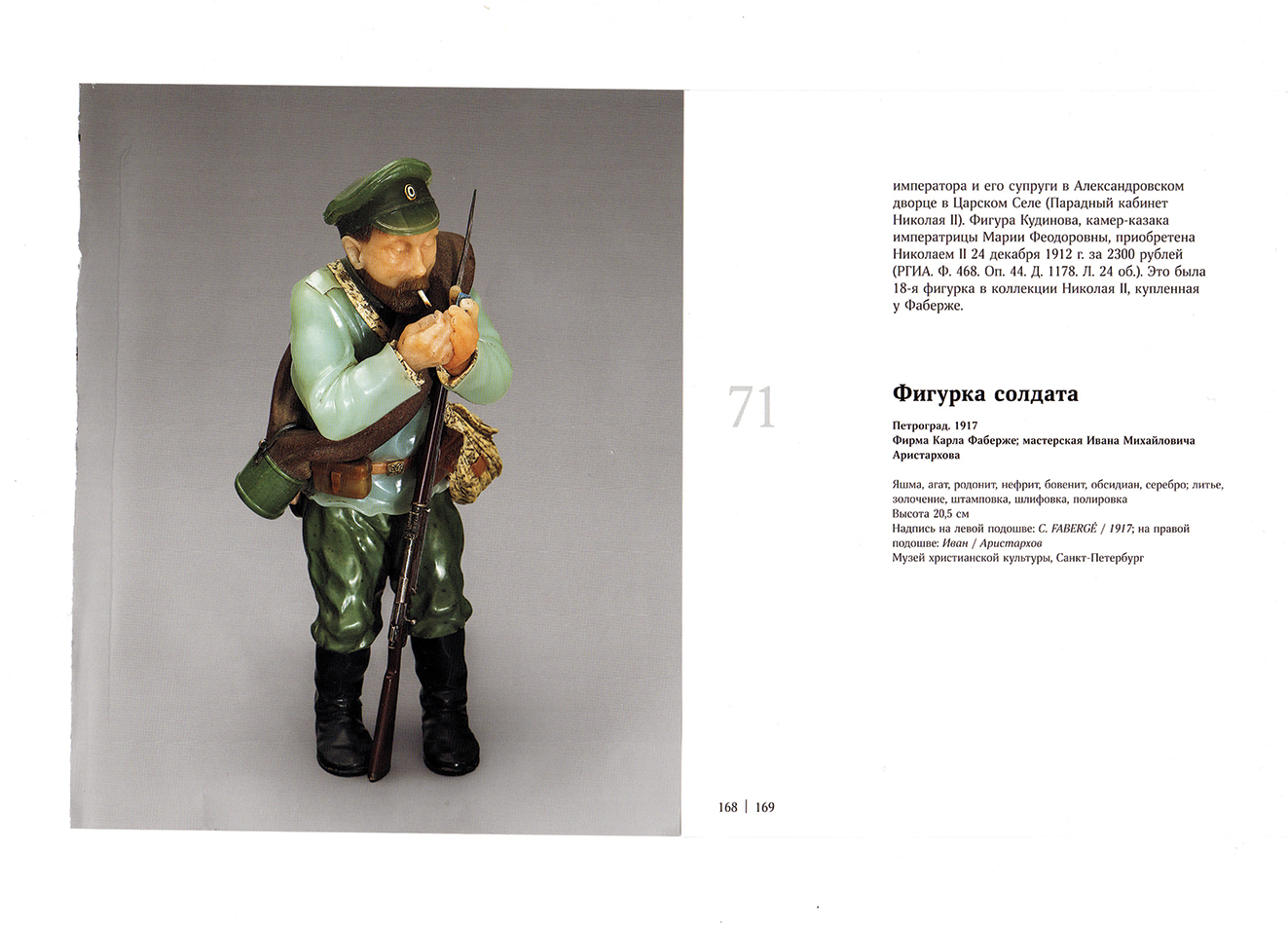

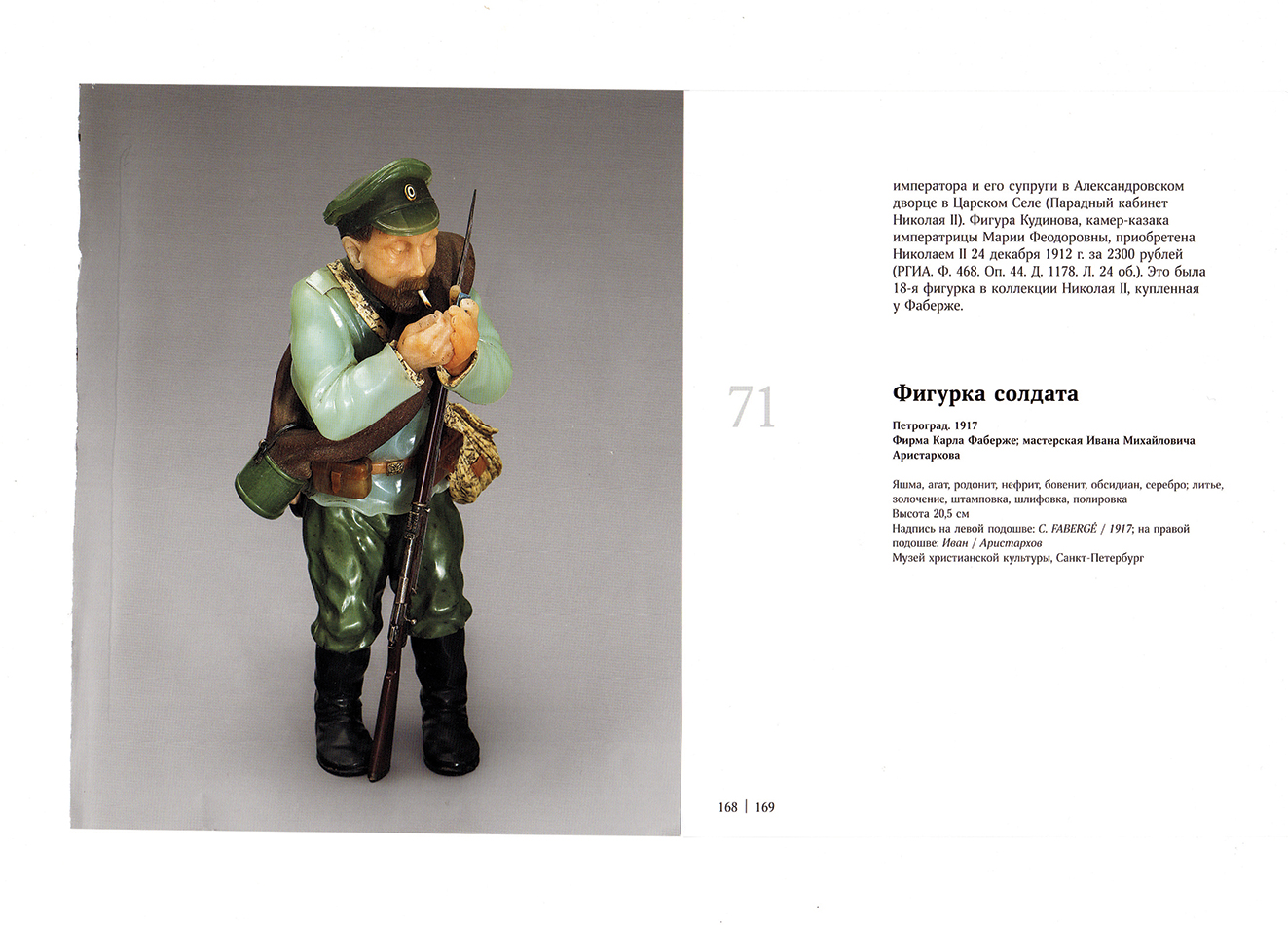

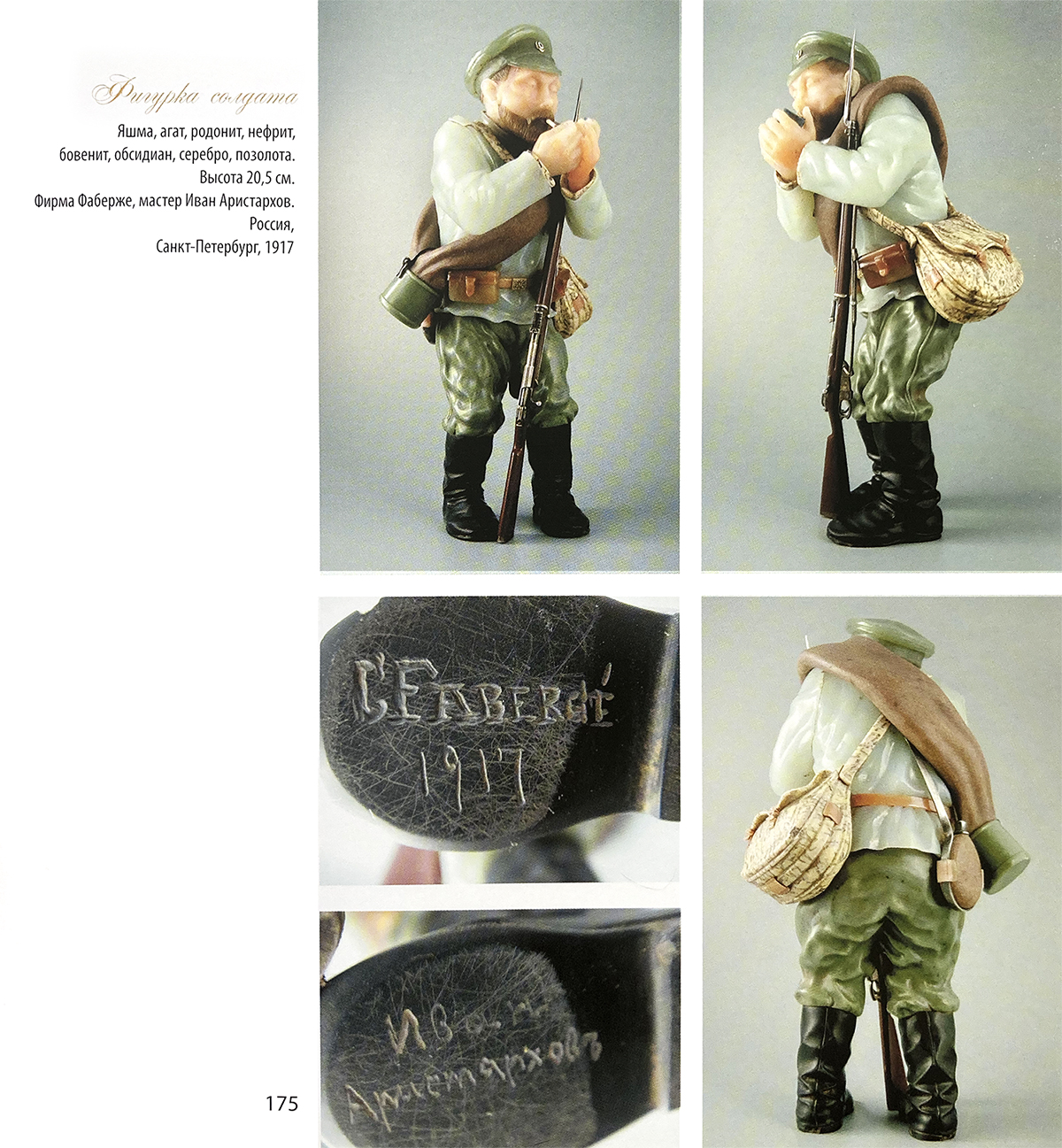

Catalogue to the exhibition Fabergé – Jeweller to the Imperial Court, State Hermitage Publishing House 2020

Technical Aspects

Fabergé’s stone-cutting technique is probably the most difficult aspect to authenticate. Hallmarks are sometimes to be found on his hardstone figures, either stamped on metal elements or engraved on stone, if size and design allowed; sometimes a Fabergé attribution is confirmed by the presence of the original, snugly fitting box. The potential findings of laboratory research – however sophisticated the equipment – are sadly limited. The age of the materials obviously proves nothing. The only thing that can help date a piece is analysis of the binder (if accessible) and the nature of the surface treatment – although this only applies to modern fakes. It is only possible to distinguish a Fabergé original from an old piece with a fake signature by art historical analysis.

Documentation

Unlike other fakes in the Hermitage exhibition, our Soldier does not even have a fictitious biography; the catalogue tells us nothing about his history… he seems to have moved stealthily, unseen and unheard of, throughout the entire 104 years of his supposed existence (going on his dated signature) – leaving not a single mention in the archives, in academic studies or at auction, and having scrupulously avoided all and every exhibition along the way (until he was allowed into those mounted by Professor Ivanov himself). Before he turned up in the Professor’s possession, this poor Soldier literally did not exist.

Authentication by documentary analysis, then, is not applicable, given the complete absence of documentation. We must therefore turn to the final weapon in the Piotrovsky armoury: ‘art historical analysis placed in context.’

Art Historical Analysis

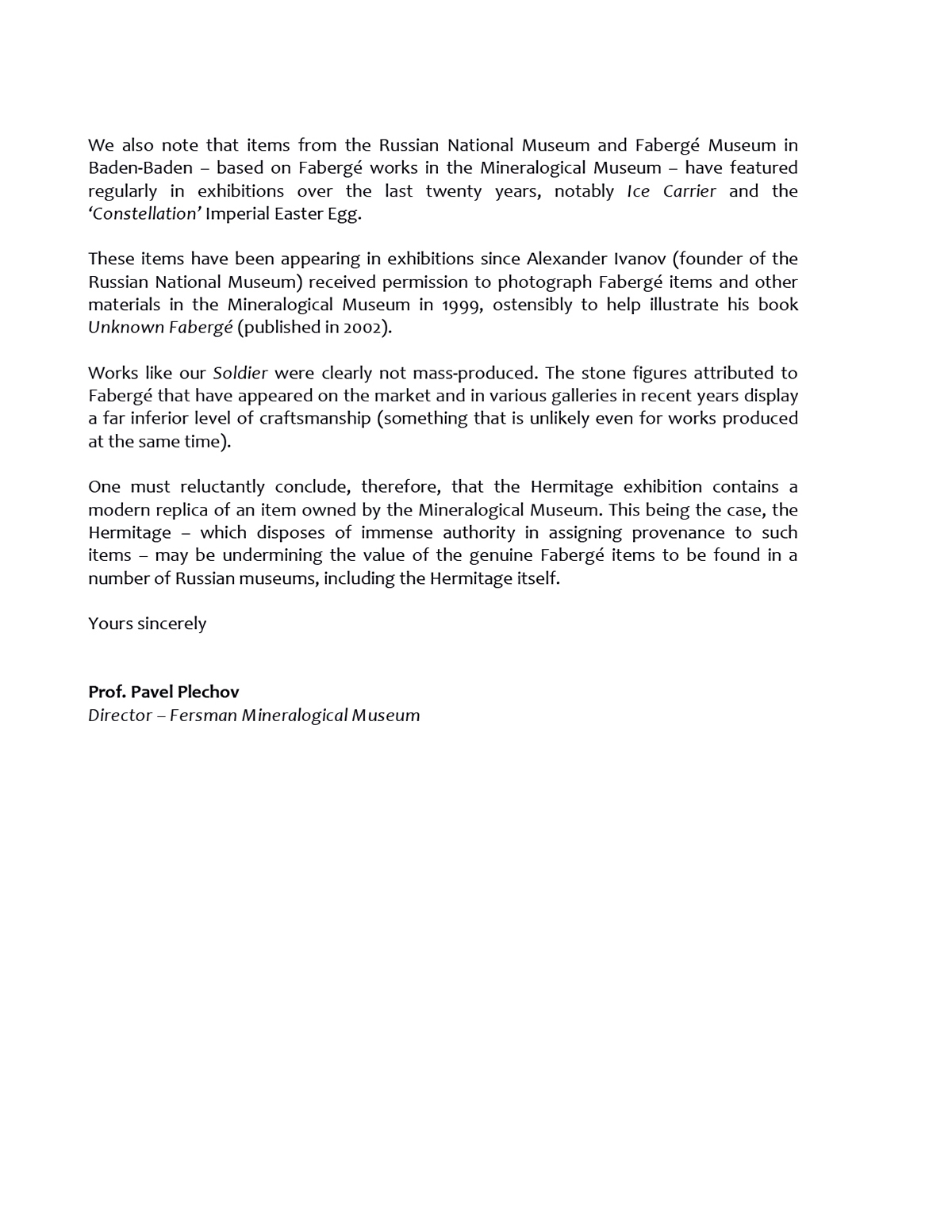

- Soldier figurine – Fersman Mineralogical Museum, Moscow

- Fake figurine in exhibition catalogue for Fabergé – Jeweller to the Imperial Court, State Hermitage Publishing House 2020

The first thing to be said about the Soldier figure on show in the Hermitage is that it is not original: an earlier version has been in Moscow’s Fersman Mineralogical Museum for nearly a century. This latter figure is well-known, and has been studied in detail; it was assigned to the Museum in 1925 by a commission whose members included Agathon Fabergé, and has since been published and exhibited many times in Russia and abroad. It was cited in Franz Birbaum’s Memoirs as one of the finest hardstone figures Fabergé ever produced – made, according to Birbaum, by Georgy Savitsky, and reflecting his ‘innate taste and powers of observation’ (History of the House of Fabergé according to the recollections of the firm’s chief workmaster Franz P. Birbaum, St Petersburg 1993, p. 31). The figurine is also signed and dated: the sole of one boot is engraved 1915 and inscribed Fabergé. In other words, it is widely and indisputably recognized as original.

Before discussing originality when it comes to Fabergé, I ought – in line with the Piotrovsky dictum – to establish the context. The Soldier is not the only copy associated with Professor Ivanov. His collection also houses replicas of the Hen Egg (the original is in the St Petersburg Fabergé Museum), Constellation Egg (original in the Fersman Museum) and Colonnade Egg (original in the British Royal Collection). Prof. Ivanov’s ‘Wedding Anniversary’ Egg combines elements from two other eggs – the Fifteenth Anniversary Egg (St Petersburg Fabergé Museum) and Basket of Flowers Egg (British Royal Collection).

Such a cluster of replicas of famous, authentic works is without precedent. Except for the Constellation Egg – which, at least, has been the subject of academic debate – none of these items have been studied by anyone except Prof. Ivanov himself. He has not only acquired a statistically implausible number of replicas but, in each and every case, was the very person who discovered them. He was lucky enough to find works which replicate those from one collection in particular: that of the Fersman Mineralogical Museum. This is all the more noteworthy in that Prof. Ivanov was granted unlimited access to the Museum’s holdings in 1999, and allowed to take detailed photographs of whatever he fancied.

Prof. Ivanov says he became aware of the Soldier figurine in 2000. It was first seen in public at the Era Of Fabergé exhibition that he unleashed on Russia’s 72nd-largest city, Kostroma, in 2011, before going on show in the Hermitage’s General Staff Building a few years later. Descriptions of the figurine have varied.

In Kostroma it was deemed to be the work of stone-carver Ivan Aristarkhov. In the General Staff Building the name of the sculptor Georgy Savitsky appeared alongside that of Aristarkhov. When the Soldier shuffled across Palace Square and into the current Hermitage exhibition, he again did so as the handiwork of Ivan Aristarkhov, with Savotsy’s name omitted, and Prof. Ivanov claiming that ‘the Fersman Museum has an Ice-Carrier by Savitsky, not a Soldier.’ After denying Savitsky’s authorship in one particular case, the Professor rejects it in all others.

The Professor based his judgment on Alexander Fersman’s Entertaining Mineralogy – a Natural Science manual for young people (published in 1937) that includes a photo of a figurine from the Mineralogical Museum, captioned as a ‘figure of an old Tsarist soldier made from various types of jasper from the southern Urals’ by the Werfel workshop. It’s not clear why Prof. Ivanov sees a contradiction here: according to Franz Birbaum, the Werfel firm collaborated with Fabergé on hardstone works and, by the time the Soldier figurine was made, had been absorbed by Fabergé altogether (History of the House of Fabergé, p. 27). The absence of the names of the sculptor and of Fabergé in the 1937 book is obviously due to the political context (we were at the height of the Stalinist Terror) and the requirements of a volume that had nothing to do with art history.

So, on the one hand, we have a well-known figurine made by a famous sculptor – owned by a State museum and abundantly studied and documented; and, on the other, a low-quality replica that has appeared from nowhere, with no documentary background (I will come to its artistic qualities in a minute) and a different attribution. Prof. Ivanov claims there is more than one such replica, and that he actually knows at least four. He declares that ‘to state that Fabergé did not create similar works is incorrect – if only because the Fersman Museum has two Fabergé Ice-Carrier figures, one of them made of bronze.’ But did Fabergé really produce replicas of his hardstone figures? The evidence emphatically suggests not.

To begin with, producing replicas runs counter to the specific requirements of hardstone carving. Plastic moulds can be used for largescale production, but not for laboriously carved individual items. Tough, hard-to-work minerals were used for Fabergé figurines. Apart from the miniature scale and the abundance of detail, this made producing such figures a painstaking process that required immense stone-cutting skill.

Then, Fabergé’s figurines were – unlike his cuff-links or cigarette-cases – never mass-produced. Fabergé figurines are almost as rare as Fabergé Easter Eggs. Probably about fifty such figurines were ever created, all of them acquired by the firm’s élite clients (cf H.C. Bainbridge: Peter Carl Fabergé, London 1949, pp 111-114; A. von Solodkoff: Fabergé’s Hardstone Figures, Munich 1986, pp 81-86; V. Skurlov, T. Faberge & V. Ilyukhin: Carl Fabergé and his Successors, St Petersburg 2009, pp 94-103). Seven such figures were purchased by Nicholas II, and six are known to have survived from Emanuel Nobel’s extensive figurine collection. Other figurines are in the royal collections of Thailand and the United Kingdom.

- House-Painter figurine – Private Collection

- House-Painter figurine – Private Collection

- John Bull figurine – Royal Thai Collection

- John Bull figurine – Private Collection

I know of about forty such figures. There is not a single replica among them. There are different versions of the same subject – like the two different House-Painter figurines (both in private collections), or the two different versions of John Bull (one in a private collection, the other owned by the Thai royal family), but I have never seen any exact replica. As for the Ice-Carrier cited by Prof. Ivanov, there is only one hardstone version – in the Fersman Museum. A second version, in the same museum, is cast in silver: definitely no replica.

I have only ever encountered ‘replicas’ when it comes to the Soldier figurine. Along with the one shown in the Hermitage, I know of another such replica in a private collection. It, too, is unquestionably a fake.

- Fake Soldier figurine – Private Collection

- Fake figurine in exhibition catalogue for Fabergé – Jeweller to the Imperial Court, State Hermitage Publishing House 2020

- Fabergé Soldier figurine – Fersman Mineralogical Museum, Moscow

Even if we did not know the original, the Soldier figurine on show in the Hermitage could never be mistaken for a genuine Fabergé due to its crude detailing, distorted proportions and an ill-conceived use of materials that runs counter to Fabergé aesthetics. The original Soldier is carved from hard, matt minerals that offer a precise colour-match. A total disregard for the stones’ characteristics gives the fake version away. For instance: instead of the original Kalkan jasper, the replica’s uniform is made from softer, translucent bowenite – which Fabergé used for watches, frames, animal figures and even the odd Easter Egg, i.e. whenever the mineral’s properties matched the artistic intention rather than contradicted it. To use a translucent, smoky, delicate pale green stone to evoke a military uniform is a somewhat extravagant choice.

Catalogue to Время Фаберже (‘Era Of Fabergé’) exhibition – Kostroma 2011

Prof. Ivanov substantiates his Fabergé attribution by the presence of a signature. Let me point out that fakes tend to have too many hallmarks rather than too few. Ivanov’s Soldier is not only (crudely) signed C Fabergé and dated 1917, it is even engraved with the name of the stonecutter, Ivan Aristarkhov. This is absolutely unprecedented, and flies in the face of the hallmarking principles of Fabergé workshops: the only signature to be found on such items was the Fabergé name itself.

Finally, perhaps the most curious assertion proffered by Prof. Ivanov is that the ageing figure hunched over his cigarette is some sort of portrait of Tsar Nicholas II. This, says Prof. Ivanov, would explain the figure’s incredible popularity and the need for a spate of replicas to be produced by Fabergé and other firms.

This idea is so absurd that I am embarrassed to have to refute it. Prof. Ivanov bases his inference on the facts the Soldier figurine has a beard, as did the Tsar, and that the Tsar once posed in a soldier’s uniform.

‘Professor’ Alexander Ivanov: Honoured Artist, Member of the UNESCO Commission for World Heritage Conservation, Expert for the Russian Culture Ministry

This caricature was supposedly made by an official supplier to the Court of His Imperial Majesty – who, far from being taken to court for making fun of his august sovereign, continued to receive and carry out top-level commissions. Of course, after the outbreak of World War One, Nicholas II cultivated an image as The People’s Tsar, and would sometimes appear in public dressed in simple marching uniform. But this did not obviate the insurmountable distance between the sovereign and his subjects. However democratic his image, it always remained conform to strict visual protocol.

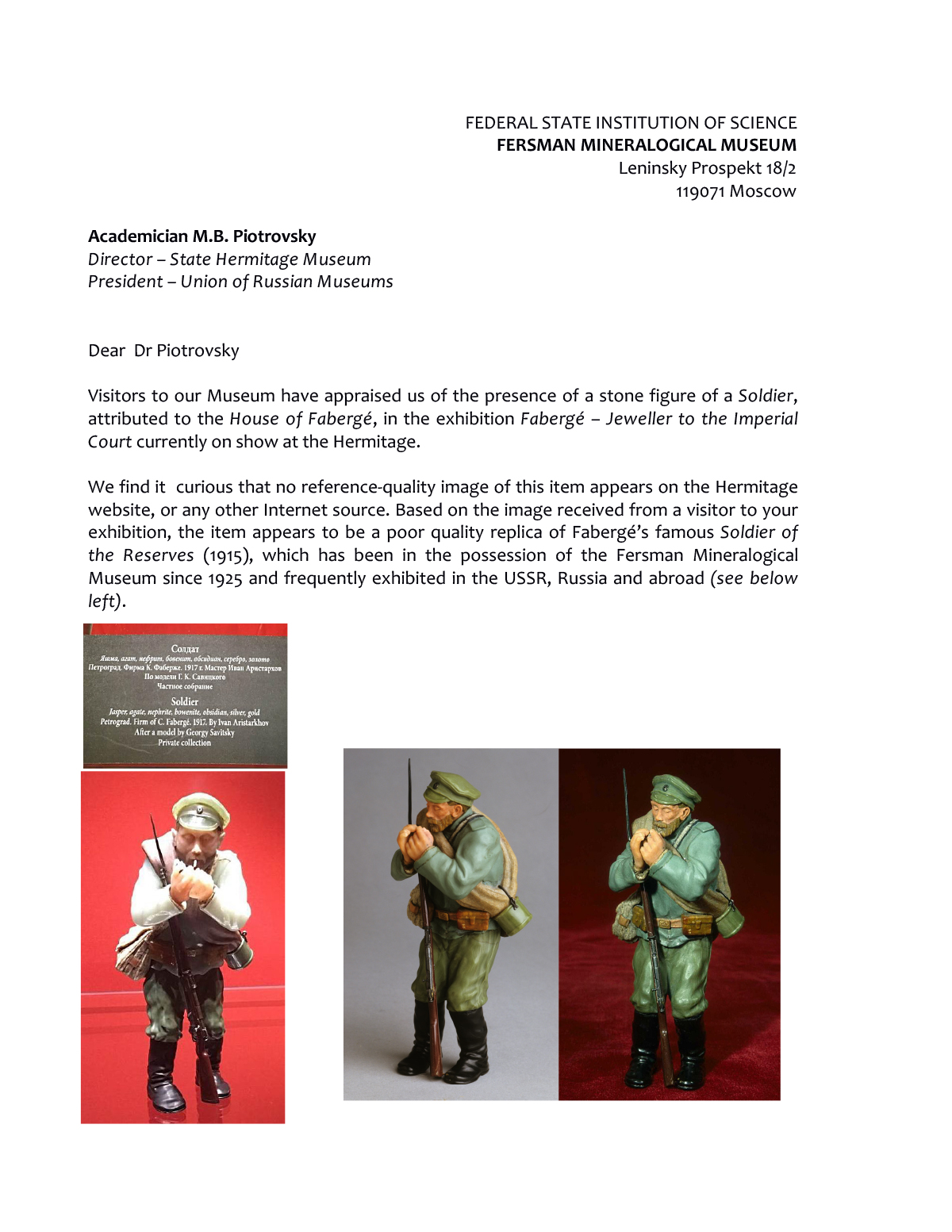

In conclusion, I reiterate my belief that the Hermitage’s Soldier figurine is a fake. My opinion is shared, and has been repeatedly stated, by staff of the Fersman Museum, whose appeals to the Director of the Hermitage have been ignored.

- Letter from Prof. Pavel Plechov, Director of the Fersman Mineralogical Museum

- Letter from Prof. Pavel Plechov, Director of the Fersman Mineralogical Museum