If there’s one auction practice that makes me mad it’s what the big firms call ‘bidding on behalf of the seller.’

On behalf of the seller? Are you kidding??

If I put something up for auction – in other words, if I’m the seller – I am not, by law, permitted to bid on that item myself. So how on earth can an auction-firm bid on my behalf?

Ludicrous.

Christie’s and Sotheby’s bid on the seller’s behalf ‘by making consecutive bids or by making bids in response to other bidders.’ Did you ever read such gobbledygook?

Probably not. It’s written in the Conditions of Sale at the back of their catalogues in print so small you need a magnifying glass to make sense of it. In other words, it’s almost impossible to read. Which is precisely the goal.

Before an auction, potential bidders are meant to sign a form agreeing to Conditions of Sale that allow the auctioneer to conjure bids out of thin air… or find them swinging from the chandelier.

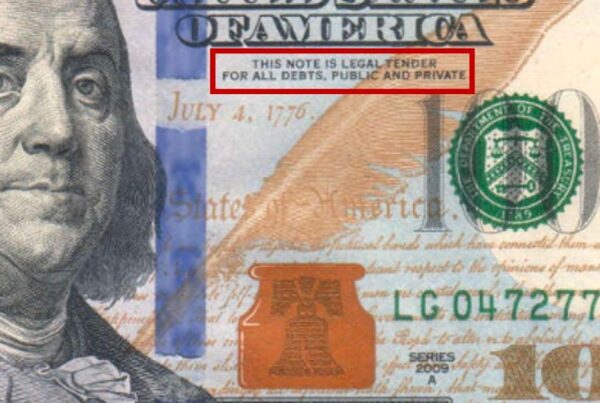

Most items at auction have a ‘reserve’ price – i.e. the sum below which they cannot be sold (usually equivalent to low-estimate). Auctioneers routinely start the bidding at a meaningless sum significantly below this reserve. Christie’s even state (see catalogue scan below) that the auctioneer may open the bidding at 50% of the low-estimate.

Lots cannot be sold until the reserve has been reached, no matter how many bids have been announced. Auctioneers gaze around the saleroom, look down at their notes, stare quizzically at their computer screens and then, in the continued absence of any bidding, suavely up the price (‘chandelier bidding’) towards the sacrosanct reserve – hoping to elicit bids from ignorant punters. If the reserve is not reached, the item is ‘withdrawn.’

What a rigmarole. Why not just start the bidding from the reserve?

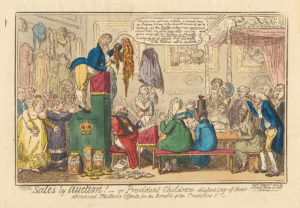

George Cruikshank, Sales by Auction!, 1819. Yale Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

That’s what they do at Hargesheimer in Dusseldorf. Their catalogues have none of this palaver about ‘low-estimates’ and high ones. The only printed figure next to each lot is the reserve – which is also the starting-price. If anyone bids, the lot is sold. What could be simpler? Or more transparent?

Some years ago a little old lady came up to me after a Russian Sale where I had bought a number of lots. She was distraught, complaining that her cherished heirloom had failed to make its $10,000 low-estimate – the auctioneer having pronounced the lot unsold (or ‘passed’) at $9,500. The lady clearly needed money, and offered me the piece for $9,500. It was of no interest and I had to decline, explaining to her that no one had bid for her item – either on the phone or in the room. The auctioneer had merely been ‘chandelier bidding.’ She couldn’t believe it, insisting that the auctioneer had been looking at somebody and said ‘Thank you everyone!’ when the bidding ended.

Art market professionals like myself are fully au fait with these nefarious tactics. It is the little old ladies of this world – and all those unfamiliar with auction sharp practice – who end up getting shafted.