NOT SO LONG AGO I saw a documentary on the Russia-K culture channel called ‘Пропавшие Шедевры Фаберже: Fabergé’s Missing Masterpieces’. It made my blood boil.

As the title implies, it’s all about rediscovered Romanov treasures. Presenter Nikolai Svistun travels the world telling Fabergé tales. He begins with the Russian Revolution and all the property confiscated from the Imperial family by Dzerzhinsky’s Secret Police. It’s a cracking story.

Then Svistun hones in on lost Fabergé eggs. The programme’s ‘expert consultant’ Valentin Skurlov pops up with the opinion that six more Fabergé eggs could be out there somewhere. Anywhere. ‘Even in Australia.’

Having set the scene, the documentary gets down to business. What’s at stake is a so-called ‘Imperial Empire Egg’ which Skurlov declares to be ‘an unquestionably authentic historical work produced by the House of Fabergé, commissioned by Emperor Nicholas II for the Easter holiday of 1902 and presented to Dowager Empress Maria Fedorovna.’

No one, outside a small group of self-interested promoters, believes the Egg is empirically imperial. No one knows where it came from. It was smuggled to London in 1996 after being ‘discovered’ by a dealer in St Petersburg. When it was offered to Aurora Fine Art Investments for $2,000,000 in 2005, my reply was unprintable – even though the Link Of Times had recently bought the Forbes Collection, and another Imperial egg would have gone down nicely.

Based on a reference in a 1922 Kremlin Armory inventory, to a ‘nephrite egg on a gold stand with a portrait of Alexander III in a medallion,’ a modern miniature of the bearded autocrat was obligingly added to the Egg in 2006. When a Gatchina Palace inventory turned up in Denmark in 2015 – referring to an ‘egg with gold mounts on two nephrite columns, and portraits inside of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna and Prince P.A. Oldenburgsky’ – poor old Alexander III was replaced by a modern double-portrait of his daughter Olga and Prince Peter of Oldenburg, who married in 1901. (Note that this Gatchina inventory talks of portraits plural, whereas the oval pearl-frame inside the egg was designed for a single portrait.)

The Egg is rumoured to have changed hands more than once, and been acquired by its current American owner in 2012. He sounds a sensitive soul. When his Egg was published by the Fabergé Research Site in 2017, a dissatisfied e-mail was received and images of the Egg removed ‘at the owner’s request.’

The article was, admittedly, entitled Fauxbergé.

The name of the owner was revealed by Svistun’s programme consultant Valentin Skurlov in a 15-page, 9,500-word ‘Opinion’ about the Egg dated 29 June 2015. This ‘Opinion’ talks about an egg inspection scrambled in New York on 27 January 2015 and attended by the Egg’s owner; Fabergé specialist Geza von Habsburg; restorer Nikolai Bashmakov; Wartski Director Kieran McCarthy; Sotheby’s Karen Kettering; the ex-Forbes Collection’s Carol Aiken; a lady from the Russian Culture Ministry; and Skurlov himself. Mr Skurlov did not reproduce the minutes of this meeting, though he did disclose helpfully that ‘the Egg was dismantled’ and ‘everyone looked.’;

A second meeting about the Egg, adds Skurlov, took place in New York on 18 May 2015. Kieran McCarthy, Geza von Habsburg, Carol Aiken and the Russian Culture Ministry opted out; in came Moscow Armory Museum Curator Tatiana Muntyan; John Atzbach (‘largest specialist Fabergé dealer in the USA and the world’ according to Skurlov); and amateur Fabergé researchers Vincent and Anna Palmade. Skurlov made a three-hour presentation, after which I hope everyone was given a stiff vodka.

I was re-offered the Egg in March 2018 for a cool €55,000,000 – by ‘Hal’ Pollock, a self-styled ‘lawyer, author, entrepreneur and songwriter’ (well, that’s what he calls himself on Twitter) from Cleveland, Ohio. Actually, I’m not so sure about the Lawyer bit – a certain Harold Pollock was ‘suspended from the practice of law’ by the Ohio Supreme Court a few years ago for ‘professional misconduct while pursuing at least 20 lawsuits on behalf of several clients embroiled in a multi-year dispute that arose largely from a real-estate development plan.’ Never mind. I’m sure Hal knows more about Fabergé than real estate. The Court also declared that Mr Pollock had ‘exhibited extreme bad faith’ and been ‘an obnoxious litigator bent on abusing the courts to further an illegitimate agenda’ – but hey, that sounds like a misunderstanding.

My pal Hal’s real forte is Art. Over the years he’s offered me Monets, Renoirs, Leonardos… you name it. As for the Fabergé – to be brutally honest, Hal wasn’t selling it himself. He was just offering me the Egg on behalf of someone called Bob.

Er, Bob wasn’t selling it himself either, but he had ‘direct’ access to the seller, the real one, in New York. The €55,000,000 included ‘a 5% commission to the buy side team’ although, temptingly, there was ‘some room in the price for a quick deal’ and the seller, or Bob, or Hal, or someone connected to them, like the janitor or the office cleaning-lady, could ‘set up a viewing with 1 day notice.’

Which was big of them, but I didn’t bother.

Hal also sent me a swanky little 90-second video filmed by David Katz (onetime official photographer of Benjamin Netanyahu) called Fabergé Wedding Egg Wedding Song V2. I’m not sure what V2 was doing in the title, except to imply that the Egg might bomb. And I didn’t know Fabergé wrote songs, but there you are – sounds like at every imperial wedding he was up in the minstrels’ gallery, strumming away on his diamond-studded balalaika, warbling on about love and happiness in his deep-throated baritone. I can’t wait for Skurlov to rediscover the lost scores of the symphonies Fabergé wrote to accompany each new Imperial Egg.

The Egg in the Katz video twirls around magically against a black background, its modern diamonds twinkling enticingly, and a ghostly white-gloved hand appearing from nowhere to press a little button at the bottom, and snap open the Egg’s front doors to reveal the modern portrait of a purportedly loving couple in profile: Grand Duchess Olga and Prince Peter of Oldenburg.

After watching the Russia-K documentary I e-mailed the Egg’s purported owner to ask if we could have a chat. No reply. I don’t blame him. I guess I’d be bashful if I was trying to flog something for €55,000,000 that you might find in a gift shop at Abu Dhabi Airport. I can just imagine Nicholas II saying ‘Come on Carl, do us something a bit cheaper and not so bloody fancy! We need to sell these things to tourists!’

It’s impossible to imagine Fabérge or his chief workmaster Mikhail Perkhin – whose extraordinary designs and sophisticated craftsmanship wowed the Belle Epoque – producing this shemozzle. It resembles no other Tsarist commission. It ludicrously features the year 1902 off-centre, flanked by clichéd laurel leaves. Just a handful of Fabergé Eggs feature their year of their creation – always centrally positioned, except for the 1893 Caucasus Egg, which respects symmetry by having one numeral on each of its four doors.

Even though the owner reckons it’s worth €55,000,000, his ‘Imperial Empire Egg’ is hardly in pristine condition. Skurlov admits that ‘some of the elements of the original egg were lost – namely a crown with diamonds, three plated monograms, and a miniature double-portrait of Grand Duchess Olga and Prince Peter of Oldenburg.’ Prospective buyers, however, needn’t be overly perturbed. ‘The lost elements’ continues Skurlov ‘were reconstructed at the request of the present owner.’

When David Katz shot his little video, the miniature double-portrait was in profiled format – inspired by the double-portrait of King Christian IX & Queen Louise of Denmark on a fluted bowenite half-column made by Fabergé around 1900 and now owned by the Queen of England.

This has since been replaced by a front-on portrait of Olga and her Prince, based on a contemporary photograph. At least, that’s how it appears in a book called Fabergé: The Imperial ‘Empire’ Egg Of 1902, independently published in 2017. Valentin Skurlov and Tatiana Fabergé are cited among the authors of this resplendent tome, alongside Moscow researcher Dmitry Krivoshey, Nikolai Bachmakov, Nicholas B.A. Nicholson (who began his career in Christie’s Furniture Department) and the Palmades. The book’s accompanying press-blurb boasts of how all these co-authors have ‘authenticated’ the Egg. Good for them. No one else has.

Mr & Mrs Palmade claim it was ‘natural and timely for Fabergé to celebrate the wedding of Grand Duchess Olga and Prince Oldenburg as the theme for the 1902 Easter Egg’ as this wedding was ‘a momentous and long-awaited event in the life of the Romanov family.’ Long-awaited? The couple had only been engaged for two months when they got married – on 9 August 1901, eight months before the Egg was supposedly delivered. Olga had only just turned 19. And the marriage was a sham. Everyone knew Prince Peter was a raging homosexual.

Even so, the Palmades describe Olga’s mother, Dowager Empress Maria Federovna, as ‘elated’ by news of the forthcoming wedding, writing to her son the Tsar: ‘I am sure you won’t believe what has happened. Olga is engaged to Petya and both are very happy.’ The Palmades artfully omit to cite the Tsar’s incredulous response: ‘Although it’s not April 1st, I can’t believe Olga and Petya have got engaged!’ he giggled. ‘They must both have been drunk!’

The marriage was a disaster from the outset, never consummated and later dissolved. In 1902 – within months of the wedding – Olga had a nervous breakdown and her hair began to fall out. Are we really to suppose that the Tsar of Russia asked Fabergé to celebrate his sister’s unhappy union with an Imperial Egg?

Column surmounted by a framed miniature of King Christian IX and Queen Louise of Denmark c. 1900. The British Royal Collection

Fabergé had already celebrated the wedding in far more modest fashion: with twin portraits of Olga and Petya by an unknown miniaturist, united by gold and diamond mounts by Mikhail Perkhin, beneath a ribboned banner rather than an imperial crown. This dainty artwork – now owned by the Hillwood Estate Museum in Washington, D.C. – measures just 4cm across.

WHEN IS AN EGG NOT AN EGG? WHEN IT’S AN URN THAT FAILS TO EARN

On 21 November 1991 ‘an urn-shaped timepiece’ with a horizontal dial appeared at auction in Geneva. It was ‘late 19th century’ and in ‘nephrite with gilt metal mounts’ –according to Sotheby’s ropey catalogue description. The mounts were actually silver-gilt, and Sotheby’s claimed without a scrap of evidence that the item had been ‘retailed by Fabergé’ and gifted ‘early in 1892’ by Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna to Dr Johann Georg Mezger for treating her daughter Olga.

The timepiece came in a Fabergé box – which, as Sotheby’s omitted to say, had obviously been intended for something else. I have dozens of original Fabergé boxes, all designed to have the contents fitting snugly – not bobbling around like this thing did. Old Fabergé boxes are easy enough to find, and much in demand for packing nefarious merchandise. Sotheby’s carefree opinion that the timepiece was ‘close in design’ to Fabergé’s Madonna Lily Egg of 1899 was pure promotional blather, and they knew it – because they gave the timepiece a paltry CHF 25,000-35,000 estimate. In the event it sold for CHF 148,500 to Michel Kamidian (a small-time dealer/runner born in Armenia) in association with Paris colleague(s).

In 1992 Kamidian helped organize The Fabulous Epoch of Fabergé exhibition just outside St Petersburg and asserted in the ugly, amateurish catalogue – which seemed to have been thrown together by a bunch of uncultured illiterates – that his urn-shaped timepiece was an authentic Fabergé egg. It was tendentiously reproduced opposite a photo of the Madonna Lily Egg (not in the show) and, even though the exhibition contained an undisputed Fabergé Imperial Egg (the Steel Egg of 1916, on loan from the Kremlin), Kamidian’s timepiece occupied the catalogue cover.

Sale Catalogue of Sotheby’s Geneva, November 1991

Kamidian had zero evidence for his Fabergé claim but, before long, his good friend Valentin Skurlov turned up a receipt in the State Archives for a jadeite Fabergé egg clock delivered to the Tsar on 22 December 1893. The date hardly squared with Mezger’s last recorded presence in St Petersburg (February 1892), and jadeite isn’t nephrite, and an egg ain’t no urn… no matter. Skurlov also ascertained that Dr Metzger was awarded the Order of St Stanislas (First Class) the very next day (December 23). ‘The indices’ he insisted ‘fall neatly together.’

The truth is doubtless more prosaic: Mezger used part of his fat fee to buy glitzy presents for his wife before he left Petersburg. These presents also included a Japanese-style jug by Ovchinnikov – currently on offer at the Theo Daatselaar gallery in Zaltbommel (30 miles east of Rotterdam) having been acquired from Mezger’s descendants.

In 1995 Kamidian found a scratched inventory-number on his timepiece that had somehow escaped Sotheby’s (and his own) eagle eyes four years earlier. Luckily his pal Skurlov – after spending ‘7 to 8 years’ building up a ‘database of more or less 30,000 Fabergé items’ – was able to date this inventory to Autumn 1893.

Kamidian showed me the clock in Paris in the late 1990s. I could tell immediately that it was not Russian but some crude, late 19th century European production.

In September 2000 Kamidian, by now apparently the clock’s exclusive owner, entered it for Fabergé: Imperial Craftsman and His World – a big show in Delaware curated by Geza von Habsburg and Alexander von Solodkoff. Neither was convinced the timepiece was by Fabergé, but they agreed to have it labelled as such when Kamidian assured them that Skurlov had found the original Faberge document in the Imperial Archives pertaining to this clock’s acquisition by Tsar Alexander III. This proved later to be incorrect, as that invoice refers to a different Louis XV-style, not Louis XVI-style, jade clock. One American specialist valued the item at $250,000 after seeing it – yet, when the timepiece was shipped from London, Kamidian had declared its insurance value as ten times that amount: $2,500,000! He also valued a hardstone Parrot by Denisov-Uralsky that he owned at $700,000. When this Parrot was offered for auction many years later, at Sotheby’s London in 2015, it didn’t even make its £80,000 reserve.

Kamidian’s timepiece suffered minor damage (to a bud and two branches) during shipping to and from the States. The insurers were initially prepared to refund 5% of the clock’s value, but withdrew this offer after expert examination concluded the damage occurred at the site of earlier repairs. Kamidian hotly disputed this and sued the organizers and shippers in 2006. The case came to court in July 2008.

Almost miraculously, a few months before the hearing, a ‘friend of Mr Kamidian’s’ discovered a hallmark and assay mark on the timepiece. These were attributed to Fabergé in court by ‘Kamidian’s expert witness’: Valentin Skurlov. It was ‘understandable’ that these marks had remained unnoticed for sixteen years, declared Skurlov, as they were both ‘extremely small and barely visible to the naked eye.’

Come off it! To suggest that the PR-savvy Fabergé would produce ‘barely visble’ marks is claptrap: he was a flamboyant salesman who wanted his hallmark seen on whatever his workshops turned out. All Fabergé pieces have hallmarks – however small. I own a tiny Fabergé compact with a hallmark just 5mm across, but it’s easily visible. On larger pieces, like this urn clock, there was plenty of room for a standard Fabergé hallmark – plus the assay mark and his workmaster’s initials.

In 1999 Kamidian showed me the clock in Paris, hoping I’d give it the Fabergé thumbs-up. Fat chance. I held it in my hands, took it apart, and examined it from top to bottom with a magnifying glass. If there were any hallmarks, I’d have seen them! It obviously wasn’t Russian.

Coincidence or not, a tiny hallmark and assay mark – and some à propos Skurlov archival material – also boosted the credentials of the 1902 ‘Empire’ Egg years after it resurfaced.

Skurlov also used ‘organoleptic evaluation’ (taste, touch and smell) to confirm the Mezger timepiece as a Fabergé. ‘From my past experience I could tell that the Egg was definitely real’ he wrote. ‘Old fabric, old glue (fish glue), old varnish, and old wood have specific smells.’ Good Old Skurlov! He can smell a Fabergé a mile off!

Skurlov didn’t just confine himself to expertise. To bolster Kamidian’s claims to mega-compensation, he weighed in with a valuation – telling the court that, if the timepiece hadn’t been damaged, it would be worth ‘around $9,000,000-10,000,000’.

What business did Skurlov have appraising things? He keeps saying he’s an academic! It’s people who trade in works of art – like dealers or auctioneers – who are qualified to make valuations, not so-called scholars!

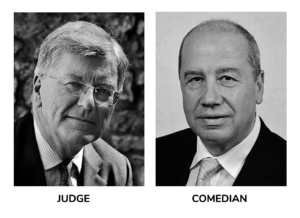

While accepting Skurlov was a ‘well-informed archivist’ the Judge, Sir Stephen Tomlinson, was ‘unconvinced that he has any significant learning or experience as an art historian…. When he expressed opinions on artistic matters his evidence was muddled and unconvincing.’

After hearing from Dr Habsburg and Herr Solodkoff that Skurlov earned money by producing certificates authenticating forgeries, the Judge was ‘left with uncomfortable doubts as to his objectivity.’

Sir Stephen was equally scathing about Kamidian, damning his evidence as ‘inconsistent, contradictory, confusing and unsatisfactory.’ He was ‘unable to find on the balance of probabilities that the claimant actually owned the clock’ which, he concluded, was not a genuine Fabergé Easter egg, worth up to £10,000,000, but a copy – worth at most £100,000. ‘Kamidian’s conduct is not consistent with a bona fide belief that the egg was by Fabergé, but rather with a belief that he might persuade a purchaser that it was.’

The Judge found the exhibition organizers liable for £1,000 damages; dismissed all other claims; and ordered Kamidian to pay costs (which, for a three-week trial at the London High Court, will have run into seven figures.)

In December 2011 the timepiece was offered by court-order at a small London auction house called Rosebery’s, where it fetched £75,000 – pretty much what Sir Stephen had predicted.

Kamidian was a sore loser – posting an on-line article (Russian Art in Danger: Fabergé in the Epicentre of International Plot) blasting Justice Tomlinson for ‘applying double standards’ and ‘vindicating those who swore to tell the truth but produced false testimonies.’ I hope for Kamidian’s sake that those paranoid allegations do not come to the attention of British legal authorities, or he’s in trouble.

Still, Kamidian received support from a meaty tome published in 2012, entitled Fabergé: A Comprehensive Reference Book and co-authored by Skurlov and Tatiana Fabergé. It contained a two-page spread extolling the Mezger timepiece as A Genuine Artefact Labelled a Fake. The book prompted one (only one) review on Amazon, posted on 16 November 2014 by Richard Wenner of the United States. ‘Of all my library on Faberge, this is the Most Comprehensive of all publications’ he reported. ‘WELL DONE Madame Faberge and Dr Skurlov.’

MORE MIRACULOUS EGGS…

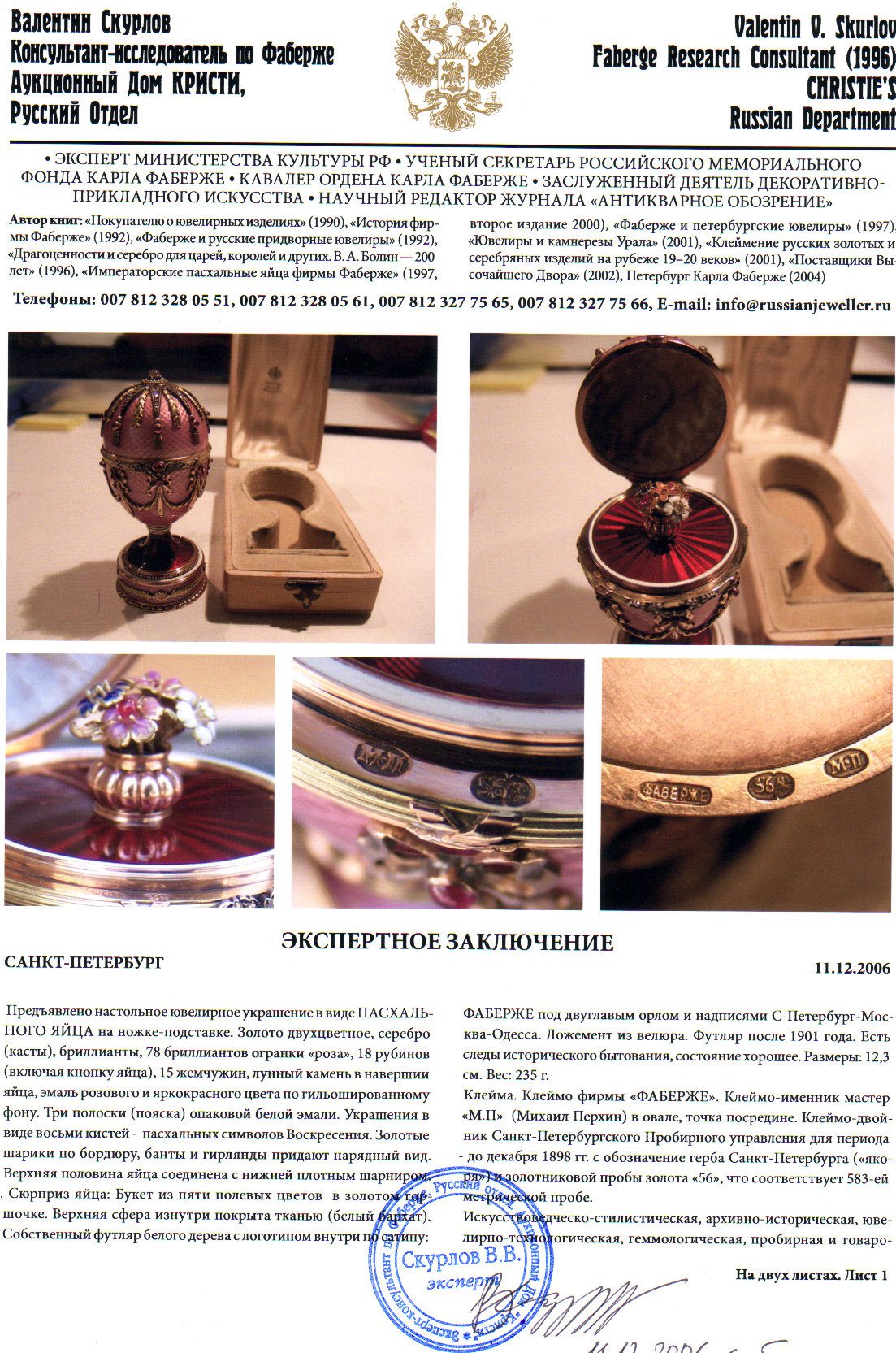

Valentin Skurlov and Tatiana Fabergé had been teaming up for years. Back in January 2007, Galerie du Rhône (a Swiss gallery in Sion, 100 miles east of Geneva) asked me if I would like to buy a Fabergé egg they had failed to sell at auction a few weeks earlier. It contained a tiny vase of flowers and had supposedly been bought from a Russian aristocrat in Basel around 1930, and housed in a French private collection since 1990.

It was an obvious fake – yet came with a kiss of Fabergé approval from Skurlov and Tatiana who, on 2 November 2006 , had ‘examined and appraised’ it and ‘mainly drew attention to the mechanism connecting the two halves of the egg.’

Fine, it’s always good to check the hinges. Fabergé did fantastic hinges – ‘the best hinges’ as someone (Donald Trump, I think) once said.

Tatiana then asked Skurlov to produce a written certificate, which he did on 11 December 2006. Excerpts:

‘The upper part of the egg is coupled to a strong lower hinge… It was made 1895-1898 in the department of gold works by the master M.E. Perkhin… By its closeness to the group of “Imperial Easter eggs”, this Easter egg has outstanding museum-collectible significance and very high antiquarian value… On the strength of its high artistic merits, the good state of preservation, its very high jewellery-technological execution belonging to a rare group of Fabergé items of the 1st class.’

First class? No one rates Fabergé by class! What’s 1st class Fabergé when it’s at home? What’s 2nd class Fabergé? What’s 4th class Fabergé? How many classes of Fabergé are there in Skurlov’s Imperial Ordering System?

I find it hard to say whether Skurlov is a crook who’ll write anything for money, or just someone who doesn’t understand Fabergé – lacking ‘any significant learning or experience as an art historian’ as Judge Tomlinson put it.

Skurlov posing with his own book

But let’s give Mr Skurlov the chance to defend himself. ‘I believe that I am known as the number one Fabergé historian in the world’ he states modestly. ‘If people have questions to ask about Faberge, I believe that they come to me first.’

That exalted status is backed by a plethora of imposing titles and impressive positions, among them: Honorary Academician of the Russian Academy of Arts; Consultant to Christie’s Russian Department; Member of the Comité des Experts of the Fondation Igor Carl Fabergé; Academic Secretary of the Fabergé Memorial Foundation; Expert Appraiser of Fine Art for the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation. All Skurlov is lacking is the Order of St Stanislas (First Class).

Skurlov’s Pink Egg certificate (below) was topped by a Russian imperial eagle and the title Faberge Research Consultant (1996) CHRISTIE’S Russian Department emblazoned in fancy lettering in English and Russian. I promptly e-mailed Anthony Phillips, then head of Christie’s Russian Department, saying I was ‘not sure Christie’s alliance with this gentleman with a rather tarnished reputation is helpful to either Christie’s or the market,’ adding: ‘Skurlov’s patron or partner Tatiana Fabergé, who is often quoted in Christie’s catalogues, has also placed her signature to a letter supporting the authenticity of this nefarious object.’

(Skurloff Certificate Translations)

Phillips replied next day. ‘I and the Russian department were unaware of the situation with this item and thank you for drawing our attention to it’ he wrote blandly. ‘I understand your concerns and will look into the situation further.’

Some years later I came across an almost identical egg to the one from Sion – same design, same height, virtually the same weight, but with different coloured flowers – in something called the Wiazemsky Collection. This ‘superior, very rare collection of 69 magnificent objects made by the best goldsmith masters active during the time of the Russian Tsars’ included 21 pieces by Fabergé – led by five eggs by Mikhail Perkin, one of them ‘possibly’ made for Tsar Nicholas II. Wow! Amazingly, this never-before-heard-of treasure-trove was ‘privately for sale’ – brokered, apparently, by the Fondation Igor Carl Fabergé in Geneva, who produced a 76-page document presenting the collection in meticulous detail. The Foundation’s address and the names of its board-members – including Mme Tatiana Fabergé, Vice-présidente – appeared at the foot of every page.

Needless to say: the collection is trash. Surely Tatiana was aware of that? I mean, come on – five Fabergé gold eggs suddenly materializing in a collection no one knew about? Yet she was Vice-President of the the Foundation that was trying to sell it. She effectively endorsed it. In all probability she was hoping for a tidy commission…. Her great-grandfather, the great Carl Fabergé, must have been turning in his grave!

Igor Carl Fabergé, a dressmaker who died in 1982, was Tatiana’s uncle. The stated goals of the Foundation established in his name include ‘promoting knowledge’ of both Carl and Igor Carl Fabergé and ‘providing help and advice to maintain and perpetuate the quality and prestige of works or products bearing the name of Carl Fabergé or his descendants.’

How the Foundation can do that by flogging dodgy caboodle beats me.

The Foundation’s other activities are derisory. Last November it supported a exhibition in Lecce, in the south of Italy. This April – until coronavirus intervened – it was meant to stage a small exhibition of photographs of Fabergé works in Versoix, a dormitory town along the lake from Geneva.

The Foundation has been chaired since 2015 by a Frenchman called Bernard Ivaldi, a consultant for more ‘educational institutions and multinational companies’ than I have room to list. His manifold expertise appears to extend from software to pharmaceuticals. Not to jewellery, alas.

Since Tatiana passed away in February, the Foundation’s Vice-présidente has been glamorous Alexandra K. Blin, Guest Relations Supervisor (i.e. Head of Reception) at the Four Seasons Hotel in Geneva. She previously worked in France marketing Bonobo jeans.

The Foundation also boasts an ‘Expert Committee’ which dares to include ‘authenticating items attributed to Carl Fabergé’ among its stated goals, and claims to boast ‘some of the world’s greatest Fabergé specialists’ among its members – who, believe it or not, include Valentin Skurlov and Michel Kamidian, alongside Bernard Ivaldi (who I don’t think has ever written about Fabergé in his life) and Galina Smorodinova, curator of an exhibition currently at Moscow’s State Historical Museum, Fabergé & Court Jewellers to the Court, where Fabergé fakes are two-a-kopeck.

Just in case the ‘Expert Committee’ needs a bit of assistance, the Foundation also has an ‘eight-person Advisory Committee’ featuring Skurlov’s Seattle pal John Atzbach – the world’s ‘largest specialist Fabergé dealer,’ as you may remember.

John Atzbach, ‘largest specialist Fabergé dealer in the world’ according to Skurlov

https://www.igorcarlfaberge.com/la-fondation/comite-consultatif/

… AND MORE IMPERIAL CERTIFICATES

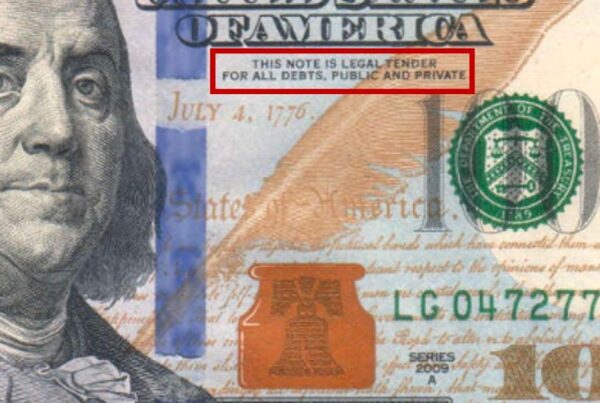

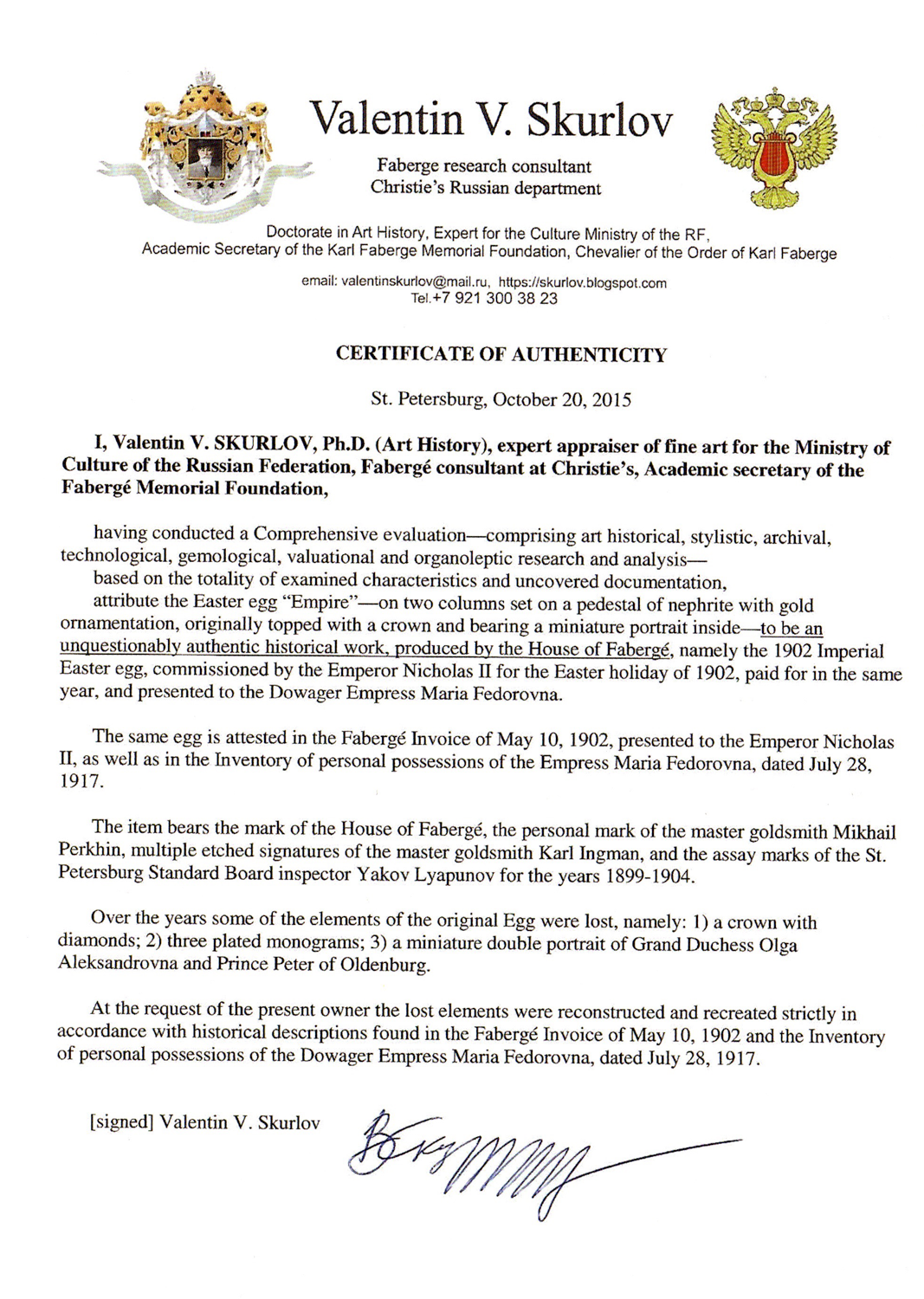

But back to the ‘Imperial Empire Egg’ – the one Russia-K made such a song-and-dance about. I forgot to mention that Skurlov produced a Certificate of Authenticity< for this too, again featuring a double-headed eagle up top, and reading like an imperial proclamation:

I, Valentin V. Skurlov, Ph.D. (Art History), expert appraiser of fine art for the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation, Fabergé consultant at Christie’s….

I have a feeling the original version of this distinguished document was written on parchment – and started We, Valentin V. Skurlov….

On 14 April 2020 I e-mailed Alexis de Tiesenhausen – Anthony Phillips’ successor as Head of Christie’s Russian Department – about Skurlov’s continuing use of certificates implying Christie’s endorsed whatever nonsense he cared to come up with. Three days later I had a reply from Armelle de Laubier-Rhally, Regional Managing Director – Old Masters Group:

‘I can confirm that this Certificate was issued by Mr Skurlov in his independent capacity and without Christie’s knowledge or involvement.’

I had received virtually the same response from Anthony Phillips in January 2007. Thirteen years later Skurlov is still issuing certificates with Christie’s name emblazoned at the top – and Christie’s are still refusing to do anything about it!

And here’s what Christie’s legal counsel Martin Wilson wrote in May 2010:

‘I confirm that we [Christie’s] have in the past turned to Mr Skurlov for advice and research. However, we have at no time permitted Mr Skurlov to make use of our name and trademark on his letterhead or on certificates that he has issued to third parties.’

Wilson made that statement to Detective Inspector Håkan Carlson of the Stockholm Police Art Fraud Squad, in connection with a court case about two Fabergé fakes entered for auction at Lauritz in Stockholm – accompanied by Skurlov certificates.

‘We kindly ask you to inform us whether Mr Skurlov is certified to issue certificates in the name of Christie’s, and has the right to use Christie’s logo and company name?’ queried Detective Inspector Carlson.

Wilson informed Carlson that Christie’s had recently written to Skurlov ‘instructing him to immediately cease making reference to Christie’s in his notepaper, certificates or other business documentation – and in his dealing with third parties.’

Correspondence between Christiés and Detective Inspector Carlson of Stockholm County Police (click here).

If Skurlov actually received these instructions he did not take a blind bit of notice of them. Ten years on he is still making reference to Christie’s in his notepaper and certificates.

Are we to conclude that he issues his certificates with Christie’s tacit approval? Why on earth would anyone who receives a Skurlov certificate suppose that it is issued ‘without Christie’s knowledge or involvement’ – when the name Christie’s appears at the top of the certificate beneath Skurlov’s name?

Anyone reading Skurlov’s Certificate of Authenticity for the ‘Imperial Empire Egg’ will automatically conclude that Christie’s endorse this Egg as an authentic work by Fabergé. If they do not, then why the hell don’t they say so?

A major Fabergé exhibition opens at the Victoria & Albert Museum in 2021. You’d expect the curator to strive might and main to secure the loan of an imperial egg that’s never been seen in public before. And you’d expect the owner of the ‘Imperial Empire Egg’ to move heaven and earth to get his precious possession into the show – because that would silence the sceptics at one fell swoop. Take it from me – it ain’t gonna happen. The Egg will continue to fly around the globe in search of another gullible nest.

The producers of the Russia-K documentary flouted the principles of objective journalism. Why, instead of soliciting a valuation from Sotheby’s or Christie’s, were we left merely with Nikolai Svistun gasping about how the Egg was worth over $30,000,000? Where did he conjure that outrageous sum from? Was he comparing it with other Fabergé sales? If so, I haven’t heard of them. As far as I know the highest price for a Fabergé egg remains the £8,980,500 ($18,500,000) paid at Christie’s London in 2007 for the Rothschild Egg presented to the Hermitage by Vladimir Putin in 2014.

When making his documentary, why didn’t Svistun speak to Wartski – a firm that purchased a plethora of Fabergé pieces from the Soviet Union back in the 1920s? Why didn’t he speak to A La Vieille Russie, who exported a host of Imperial eggs from the USSR and helped assemble the Forbes Collection – with its nine Imperial eggs – now owned by , and on permanent show at the Fabergé Museum in St Petersburg? Why didn’t he speak to Fabergé Museum Director Vladimir Voronchenko, and ask him the obvious question: Why isn’t your museum, which has the largest Fabergé collection in the world, keen to buy this unique item?

Was the Russia-K documentary a genuine effort to make a serious programme by an amateurish journalist out of his depth – or a PR stunt commissioned and/or bankrolled by the Egg’s current owner ?

None of the world’s major Fabergé dealers have expressed an interest in this egg. None of the world’s top Fabergé experts have endorsed it. Sotheby’s and Christie’s would fight to the death to sell a genuine, market-fresh Fabergé Imperial Egg – but I’m sure they won’t go near it.

It’s a cracking story all right – but the Egg is rotten to the core.