PICTURES

There was a healthy gathering at Sotheby’s on Tuesday 30 November – albeit no comparison with previous times, when the Russian contingent was out in force and anybody and everybody spoke Russian. Now it’s more like half-and-half. In the good old days you needed to come half an hour early to get a chair – now, if you’re late, you don’t have to worry about having to stand.

This 220-lot picture sale was notably better than Christie’s, with 160 lots selling (72%) and a total of £8.4 million.

No matter how many Ayvazovskys appear on the market, they all seem to pull in pretty stiff prices. Lot 1 was a case in point: a puny, pretty, postage-stamp sized Ship At Sea that sailed to £176,400 against an estimate of €50,000-70,000.

- Lot 5, Ivan Aivazovsky, A Pair of Southern Italian Views: View of the Gulf of Naples from Posilippo with the Palazzo Donn’Anna, New Moon

- Lot 5, Ivan Aivazovsky, A Pair of Southern Italian Views: View of the Bay of Pozzuoli on a Moonlit Night, with the Islands of Nisida and Ischia in the Background, Full Moon

Then came a pair of museum-quality Ayvazovsky views done in 1844: one of the Bay of Naples, the other of the Gulf of Pozzuoli just along the coast. They’re the earliest Ayvazovskys I’ve ever seen – and rightfully made it to seven figures, reaching £1,007,2000 (Lot 5, est. £600,000-800,000). I thought they would do even better than that – they’re very rare and very attractive.

Meantime a couple of wonderful, if faded, Piratsky watercolours of Officers and Soldiers remained unsold (Lots 3/4, est. £40,000-60,000 each). So did Petr Sokolov’s Borki Train Disaster (Lot 11) despite a moderate £80,000-120,000 estimate, and even though it’s a very interesting picture. It belongs in a museum.

Another star lot, Savrasov’s The Volga near Yurevets (Lot 20, est. £800,000-1,200,000), made it £983,000. This is a well-known painting, with evident similarities with Repin’s famous Barge-Haulers, but has spent most of its life outside Russia and, according to Sotheby’s, was consigned from France. At roughly 126.5 x 207cm this is probably Savrasov’s largest known painting. It’s rather monochrome, and less to do with Russian beauty than evoking the country’s big, vast nothingness – I guess it’s kinda grim, and not exactly very attractive, but it’s an important museum-level picture.

- Lot 20, Alexei Savrasov, The Volga near Yurevets

- Lot 33, Ivan Pokhitonov, Château d’Anglet près de Biarritz

The Wanderers were hardly known for painting pretty women, but a couple by Konstantin Makovskys surfaced here. His Maria Matavtina Reclining (1892) rated a mid-estimate £252,000, but to call this painting attractive would be wildly overstating the case – it’s empty and shallow, and if it hadn’t been by Makovsky no one would have been in for it (Lot 26). A topless Makovsky Odalisque, on the other hand, was a beautiful, rare and wonderful picture, and well worth £214,000 (Lot 30, est. £80,000-120,000).

A quartet of girly Harlamoffs fresh off the conveyor-belt all sold quite well. I thought collectors had lost interest in these. They appear in every bloody sale – often what seems like the same model painted from different angles, which is sort of boring. The girl on the left of Friends (Lot 27), sold for £88,200, popped up again as the Girl Crocheting in Lot 32, selling for a mighty £182,700.

Pokhitonov used to bring serious money a few years ago, when two collectors were going for him hammer and tongs. Apparently their fervour has cooled, hence today’s more moderate estimates and rather bleak results. An 1888 landscape near Biarritz was bought in (Lot 33, est. €100,000-150,000). His Ruelle à La Panne (1895), a misty Belgian street-scene, made do with a low-estimate £47,880 (Lot 34).

A nice 1919 Kustodiev Village Fair (Lot 46, est. £200,000-300,000) was unsold but a charming 1933 Gorbatov View of Pskov took a solid £100,800 (Lot 41) and a couple of colourful Stelletskys both doubled estimate (Lots 47/48). The best of three pretty stage designs by Sudeikin soared to £113,400 (Lot 51, est. £30,000-50,000). Three stage designs by Korovin showed an artist in sad decline, but such is the Korovin name that a group of figures dancing outside a chalet – a study for Pugni’s ballet Конeк Горбунок (‘The Little Humpbacked Horse’) – trebled hopes with £63,000 (Lot 56).

- Lot 46, Boris Kustodiev, Village Fair

- Lot 59, Petr Konchalovsky, Still Life with Teapot and Tray

A triple-estimate £1,043,500 for a boring Konchalovsky Still Life with Teapot and Tray was a formidable result. Konchalovsky had his off-days, and I would never call this a masterpiece of any sort (Lot 59).

Petrov-Vodkin’s earnest but unexciting Still Life with Apples (1912) was meant to head the sale, but was withdrawn for reasons unknown (Lot 62, est. £2,000 000-3,500,000). I failed to elicit comments from Sotheby’s as to why, all I received was a typical glib statement ‘it’s, confidential’. Another big name, Goncharova, was represented by an undated Still Life with Sunflowers that failed to sell. Was I surprised ? Not really. It probably should have sold, but it ain’t no Van Gogh (Lot 63, est. £180,000-250,000).

Other not unexpected failures included an ugly, laughing Maliavin Baba (Lot 98, est. £25,000-35,000) and Serebryakova’s 1932 Moroccan Girl (Lot 114, est. £80,000-120,000). A bunch of average auction-fillers took us to a 140.5 x 181cm Stalin and Voroshilov in the Kremlin after Gerasimov. I was emphatically not surprised to see this bomb, though if the estimate had been more reasonable, and the thing a quarter of the size, I might have bought it for my toilet wall (Lot 148, est. £50,000-70,000). Unsold too, alas, was Nalbandian’s (Lot 156, est. £6,000-8,000) 1963 portrait of Dyedushka Lenin, the great friend of children, killer of their parents and beloved Людоед (cannibal). What the hell is the matter with Russians – they revere their executioners and commemorate them. When will they dump all relics of the murderers whose stench pollutes the Red Square?

Then came some strange names I’d never heard of. Some sold for meagre numbers. Some didn’t. The stuff was of such low quality, no wonder. £2,520 for Vladimir Yakovlev! £1,890 for Üllo Sooster! I understand that getting hold of decent caboodle is tough these days, but how low is low? I recall Sotheby’s claiming not so long ago that they would not touch pictures worth less than £10,000! Whatever happened to that proud policy? New management I hear is more into money than old standards.

Babentsov, Matushevsky, Tikhomirov… all unsold. Only Tatiana Yablonskaya escaped the carnage, with a mid-estimate £18,900 for her Winter Day (Lot 164).

The session’s final 43 lots were devoted to contemporary crap, of which 32 found takers. Dubosarsky & Vinogradov’s enormous Honey, I’m Still at the Office (1996) sold to the only bidder for £50,400 (Lot 211). I would love to own this painting, but people might get the wrong idea, and find its playful nudity disconcerting. Whoever bought it must be a guy with great taste and guts. I do not know many wives who would welcome such purchase for the living room. The thing may be a bit crass, but it’s certainly not devoid of humour and reality!

Sokov’s Marilyn and Stalin took £60,480. Amazing! Sokov was no painter. What can he have been getting at here? What’s the big deal? Stalin was hardly a Kennedy-style womanizer. Was Sokov trying to be funny? His sense of humour must have been pretty adolescent (Lot 202, est. £30,000-50,000).

Kabakov’s In The Store fetched £151,200. Is it meaningful? No, it’s crap. It’s obviously attempting to say something – but how is the viewer expect to understand what? And it’s 3.5 metres long! One metre could easily have been chopped off from the side, and also a chunk in the middle. It’s empty. Nothing there. An Emperor’s New Clothes of a painting (Lot 205, est. £120,000-180,000).

- Lot 211, Vladimir Dubossarsky & Alexander Vinogradov, Honey, I’m Still at the Office

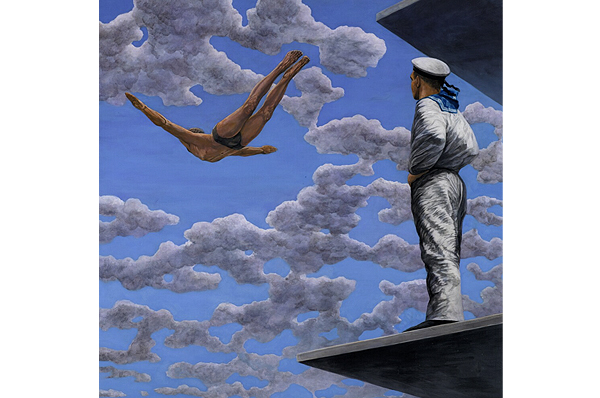

- Lot 206, Georgy Gurianov, The Dive

Dmitry Shorin’s Sitges has a car floating or sinking into the Mediterranean (I’m presuming the work’s title refers to the Spanish coastal town), with a flying dog in the foreground (Lot 215). Funny? Witty? I hardly think so. What’s it all about? I’d like to understand what’s going on… and just who can have wanted to pay £20,160 for this infantile nonsense. With Dubosarsky & Vinogradov you can clearly see what they’re getting at: poking fun at the regime, like Komar & Melamid (whose works are also nicely painted). Shorin is nowhere near their league.

Guryanov’s The Dive pulled in £144,900. There seemed to be no great meaning behind this gay portrayal of a sailor watching a diver, but at least we knew what was going on, and it has some nicely painted clouds (Lot 206, est. £40,000-60,000).

WORKS OF ART

Sotheby’s 290-lot Works of Art sale brought £3,300,000, and were 61% sold by lot. A ‘rare and impressive’ goat’s head table-box by Wigström, in far-from-rare bowenite, got things going with £60,480 (Lot 401, est. £30,000-50,000).

I hate this business about ‘rare and impressive’ – to whom? who is the judge of ‘rare and impressive’? Another good one is ‘from an important collection’ – great example of empty verbiage.

A rather disappointing £327,600 (£260,000 hammer) greeted the rock crystal and nephrite Apple Blossom (Lot 405, est. £150,000-250,000)… the same sum that Christie’s got for their Strawberries. I think the Apple Blossom is a great piece. Given its Imperial and Rockefeller provenance, it should have fetched more.

- Lot 405, A Fabergé jewelled gold-mounted guilloché enamel, rock crystal and nephrite model of an apple blossom

- Lot 406, A Fabergé jewelled gold-mounted en plein enamel, rock crystal and nephrite model of a violet

One of Sotheby’s most expensive lots – a puny study of a Violet (Lot 406, est. £250,000-350,000) – failed to elicit a single bid. No wonder. It was peddled for some time on a cheap antiques platform called 1stDIBS, which sells space mainly to low-end dealers and audaciously charges hefty commissions in a manner similar to the rip-off practices of major auction firms. 1stDIBS provides no expertise or worthwhile services – just a spot in dark, murky cyberspace. The unsold flower is a cute little thing. It last appeared at auction in October 2014 at Sotheby’s New York, when it fetched a premium-inclusive $281,000 (then equivalent to around £175,000) – so whoever consigned it to Sotheby’s London (rumoured to be the New York trade) was looking to get rid of this thing with little or no profit. Now the piece is dead for a few years unless market does a major turn-around.

A Wigström study of a Pansy barely squeaked through at £69,300 (Lot 407 est. £60-80,000). Also cute, but also puny.

Perkhin clocks had a tough ride – only one of five sold: a blue-enamelled triangle, and that for a very modest £13,860 (Lot 423, est. £15,000-25,000).

The failures began with a nice silver and guilloché enamel clock – a perfectly legitimate Fabergé clock in good nick (Lot 440, est. £60,000-80,000). There were no bids at £60,000. The combination of grey-mauve enamel, surmounted with pale gilding and a rather common stock fru-fru, is bland and charmless.

Calling a clunky bowenite desk clock bereft of elegance and finesse ‘rare and early’ wasn’t enough for Sotheby’s to flog it (Lot 447, est. £50,000-70,000). The ‘early’ days of good old Carl hardly brimmed with the masterpieces over which we drool today. The description of ‘rare and early’ is quite true: I do not recall seeing another clock of the same ilk. I can’t say that my Fabergé education has suffered as a result.

- Lot 410, A Fabergé silver-mounted guilloché enamel and dendritic agate desk clock

- Lot 456, A Fabergé silver and enamel desk clock

A standard-sized, blue enamel, run of the mill desk clock was another casualty (Lot 456, est. £25,000-35,000). These days Plain Janes evoke little emotion – low estimates notwithstanding. Give me something juicy, sexy and sumptuous! Why waste money for common goods?

The square white ‘cockroach’ clock was another failure – I guess there are still people with taste in this world! (Lot 410, est. £45,000-65,000). Another Fabergé ‘cockroach’ clock – triangular this time – turned up on December 2 in Milan, at an auction outfit called Il Ponte (lot 130). This was a flat, mauve enamel clock, and its design was certainly out of the ordinary, I must confess. In fact, I’ve never seen such clocks. The condition was questionable, with weird protruding studs in the corners causing lots of questions. Do they add to the design? – The hell they do! My guess is that they are later additions intended to hide flaws. With typical Italian efficiency, Il Ponte ignored my request for high-res JPGs (a friend of mine received the same treatment). Results posted on their website show €60,000 hammer – below estimate, but not bad (if you can trust it) for a dubious item and a deficient advertising campaign.

- Il Ponte, Lot 132, A Fabergé jewelled, gold-mounted silver-gilt and enamel clocks

- Il Ponte, Lot 130, A Fabergé jewelled, gold-mounted silver-gilt and enamel clocks

Another Fabergé clock, this time in white enamel, featured at the same Italian sale (lot 132). This was of a plain square design, with applied olive leaf ornament embellished with small red cabochon beads. A few leaves have fallen off – but that’s no big deal… a small job for a good jeweller. But, to reclaim its original beauty the clock, needs a serious bath – God knows where it can have become so filthy… perhaps in the company of hardcore consumers of Gitanes or Marlboros. It hammered for €80,000, topping its high-estimate by ten grand – a respectable result.

Back at Sotheby’s. After the clocks came a clutch of small enamel eggs, jewellery and bits and bobs. Some sold, some didn’t. Whatever sold didn’t make a lot. No surprise there – there was nothing for a proud and astute collector to stick in his vitrine and enjoy for ever after.

Then we got to the Fabergé animals. Nearly all sold. Most were from bowenite – had they been made out of different stone they’d probably have made much higher prices. Bowenite, hardly my favourite stone, looks like used soap. The pick was a Kermit-looking gold-mounted Frog doing a hand-stand at a double-estimate £63,000 (Lot 458). An ugly, poorly carved Mystic Ape in pale green bowenite, catalogued as ‘Fabergé, just made it to the reserve with £25,200 (Lot 460, est. £25,000-35,000). A bowenite Elephant was offloaded for a pawky £8,190 (Lot 463, est. £8-12,000). Why this was called ‘Fabergé’ I’ve no idea. ‘Probably, possibly, attributed’ would have been good in front of the description.

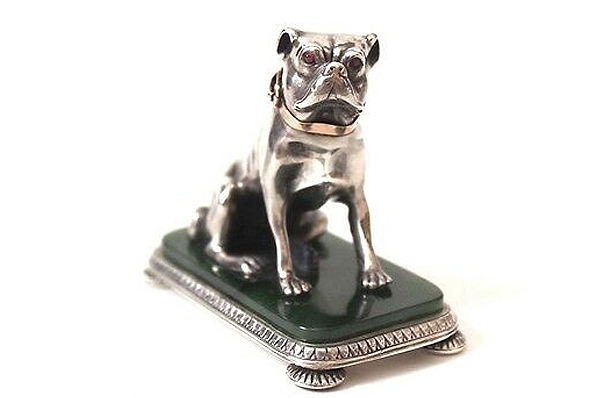

- Lot 461, Jewelled gold-mounted nephrite model of a pug according to Sotheby’s

- Fake Fabergé bulldog

- Fake Fabergé bulldog

One critter that didn’t sell was Lot 461, an important Fabergé jewelled gold-mounted nephrite model of a Pug carved from dark green Siberian nephrite. How can you call a small, 2½-inch dog carving ‘important’? Sounds ludicrous. Dogs can be cute, lovely, pretty, cuddly, even adorable… but important? Give me a break! Political events can be important, scientific discoveries can be important…. The Oxford English Dictionary defines important as ‘having a great effect on people or things; of great value.’ This hapless hound had no effect on the saleroom other than provoking indifference or suspicion, and the only people valuing it at £40,000-60,000 were the Sotheby’s ‘experts’ who came up with its estimate. True, it had impressive-looking provenance – having belonged to Sir Bernard Eckstein (1894-1948), a noted art collector who donated works to the V & A, British Museum and other institutions. But Fabergé ‘science’ has advanced considerably since the old days, and many attributions have been since modified or need re-appraising. If you Google Fabergé Bulldog, dozens of almost identical models will appear in your screen – which maybe caused concern among potential bidders about the origins of the beast in question.

Another Elephant, this time in jasper, did better at £12,600 (Lot 468 est. £7,000-9,000). An equally ugly Elephant, this time in purpurin, was catalogued as ‘probably Fabergé’ although, in terms of (lack of) quality, I couldn’t see any difference between the two. The Elephant failed to sell (Lot 469, est. £5,000-7,000). Despite catalogue hoo-ha about a ‘nearly-identical Fabergé Hen’ being commissioned for Edward VII, the next lot – a purpurin Hen – did not elicit much competition. The £11,340 price reflected its hideous quality and a lack of trust among potential buyers (Lot 470, est. £8,000-12,000).

These three lots – 468-470 – were all atrocious. Two sold after a bit of a fight, but no serious blood-letting. How can you prove and provide a guarantee of authenticity when a carved animal comes without the original box or any hallmarks or scratched inventory numbers? To prevent possible aggravation of lawsuits wouldn’t it be wiser to throw in words like ‘probably, likely’, etc.

After more bloody eggs, and a series of cigarette cases that sold for very little, came a trio of nice Fabergé silver animals. The only one to sell was a Dolphin salt-cellar by Rappoport at £15,120 (Lot 487, est. £7-9,000).

NON-FABERGÉ

Then come pots, pans and all sorts of kitchen utensils – decanters, cut glass, silver. All equally boring. And that applies to the porcelain. We’ve seen it all many times, especially the military plates. There seems to be a never-ending supply. They predictably did well, bringing from £37,800 to £56,700.

A run of the mill Imperial Porcelain vase from the reign of Nikolai I (1825-55), just 72cm tall, sold for £201,600 – a far cry from what these things were selling for 15 years ago, so no great investment (lot 531, est. £100,000-150,000). Two cache-pots with beautiful floral paintings made £113,400 (Lot 534, est. £80,000-120,000).

From lots 535-553, we had a miscellaneous array of 19th century Russian porcelain: only five lots sold for derisory prices. Porcelain activity was very sparse – only a few lots created any interest among bidders.

- Lot 586, A Soviet porcelain vase, Lomonosov State Porcelain Manufactory

- Lot 583, RSFSR: A Soviet Propaganda Porcelain plate, State Porcelain Factory

Then came 19th century figurines – boring, boring – and some of that never-ending Soviet porcelain I absolutely hate. Lord knows where it all comes from. Hardly any of it sold. Most of the designs we’ve seen before. A couple of propaganda plates squeaked through at £10,080 (Lot 583) and £7560 (Lot 585).

But a bulbous 1932 Lomonosov vase painted with acrobats and dancers after a design by the enigmatic G. Kuznetsova sold for a bunch of money – £47,880. God knows why! Maybe it’s rare, but it’s also devoid of quality (Lot 586). And a taller vase from 1928, illustrating a Soviet rescue mission in the Arctic, sold for £88,200 (Lot 590). Jesus! Why do collectors long for a Soviet past that ruined the lives of so many (and created hardly any art worth speaking of)?

Enamels fared poorly – 10/23 lots (43%) sold. The best was a two-handled bowl by Rückert at £60,480 (Lot 592, est. £30-40,000). Then came some cigarette cases, one nicely enamelled, but mostly nothing to look at. Then the icons: no big shakes, but some did pretty well.

A silver-gilt and cloisonné enamel icon of Christ Pantocrator by Ovchinnikov took £126,000, double top-estimate – a formidable result for an icon that was nice enough but nothing to write home about (Lot 620, est. £40-60,000).

Just as unexpected, in my book, was the double-estimate £35,280 lavished on a very average Ovchinnikov icon of St Alexander Nevsky (Lot 628) – apparently somebody needed a hefty Christmas present for some big Sasha. And an icon of St Anna of Kashin from the Moscow workshop of Alexei Vashurov sped to £47,880 – here again, I guess somebody needed an urgent gift for their little Annushka (Lot 653, est. £20,000-30,000).

Much finer, in my opinion, was the beautifully painted miniature-style icon with maker’s mark I.Zh (Moscow 1886), showing St Nicholas the Wonderworker and the Archangel Michael, that in comparison with previous lots brought modest £35,280 (Lot 652 est. £20,000-30,000).

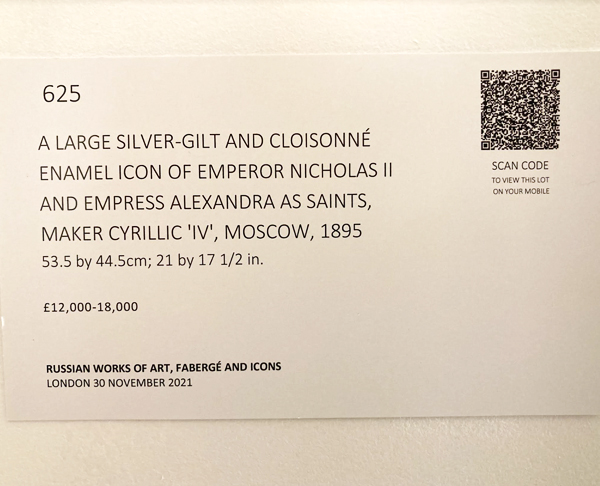

- Lot 625, A large silver-gilt and cloisonné enamel icon of St Nicholas and St Alexandra

- Lot 625 description

The third-rate circa 1900 icon of St.Nicholas and St.Alexandra Sotheby’s ‘experts’ ludicrously claimed to depict the Tsar and his wife as SS Nicholas & Alexandra. The illiterate “genius” who wrote the description obviously did not know that both were killed in 1918 and canonized in 2000. Boy, did I have a chuckle over this! I know many other people did too. Despite this grievous stupidity on the label the icon made a respectable £15,120 (Lot 625, est. £12,000-18,000).

The silver-gilt and cloisonné enamel icon by Galkin was unsold, which serves Sotheby’s right for their amateurish attempts to translate its plaque (Lot 627, est. £12,000-18,000). Surely, to avoid hysterical blunders there are people around who could help with both icons and Russian history. Call me, I’d be happy to help!

The bits of mediocre silver created no surprises. Most didn’t sell, notably an elaborate, lion-topped presentation cup with stand by Ovchinnikov (Lot 683 est. £25,000-35,000). A good-looking, chased silver tankard also by Ovchinnikov just made its reserve at £8,190 (Lot 684, est. £8,000-12,000),

No news on the bronzes: the same doldrum scenario. Whatever sold did so at the low end.

*

Russian Week sales totalled £33.8 million all in all. Over half that sum (£17.7 million) was generated at Sotheby’s, nearly one-third (£11.1 million) by Christie’s – leaving MacDougall’s and Bonhams with a combined market-share of just under 15%.