Exhibitions

Icons and Easter Eggs Of Imperial Russia, St Mary’s College of California, Moraga, March 18 – April 30, 1995

Russian Art of the Nineteenth Century: Icons and Easter Eggs. A Postmodern Perspective, Patrick and Beatrice Haggerty Museum of Art, Marquette University, Milwaukee, 16 April – 28 July 1996

Bibliography

A. Ruzhnikov, A. Harlow, Icons and Easter Eggs Of Imperial Russia, St Mary’s College of California, Moraga, 1995, no. 14, illustrated in colour p. 9

C.L. Carter, Russian Art of the Nineteenth Century: Icons and Easter Eggs. A Postmodern Perspective, Milwaukee, 1996, no. 5, p. 54, illustrated in colour p. 21

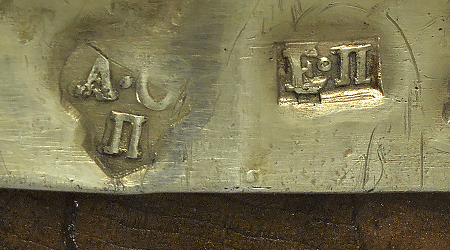

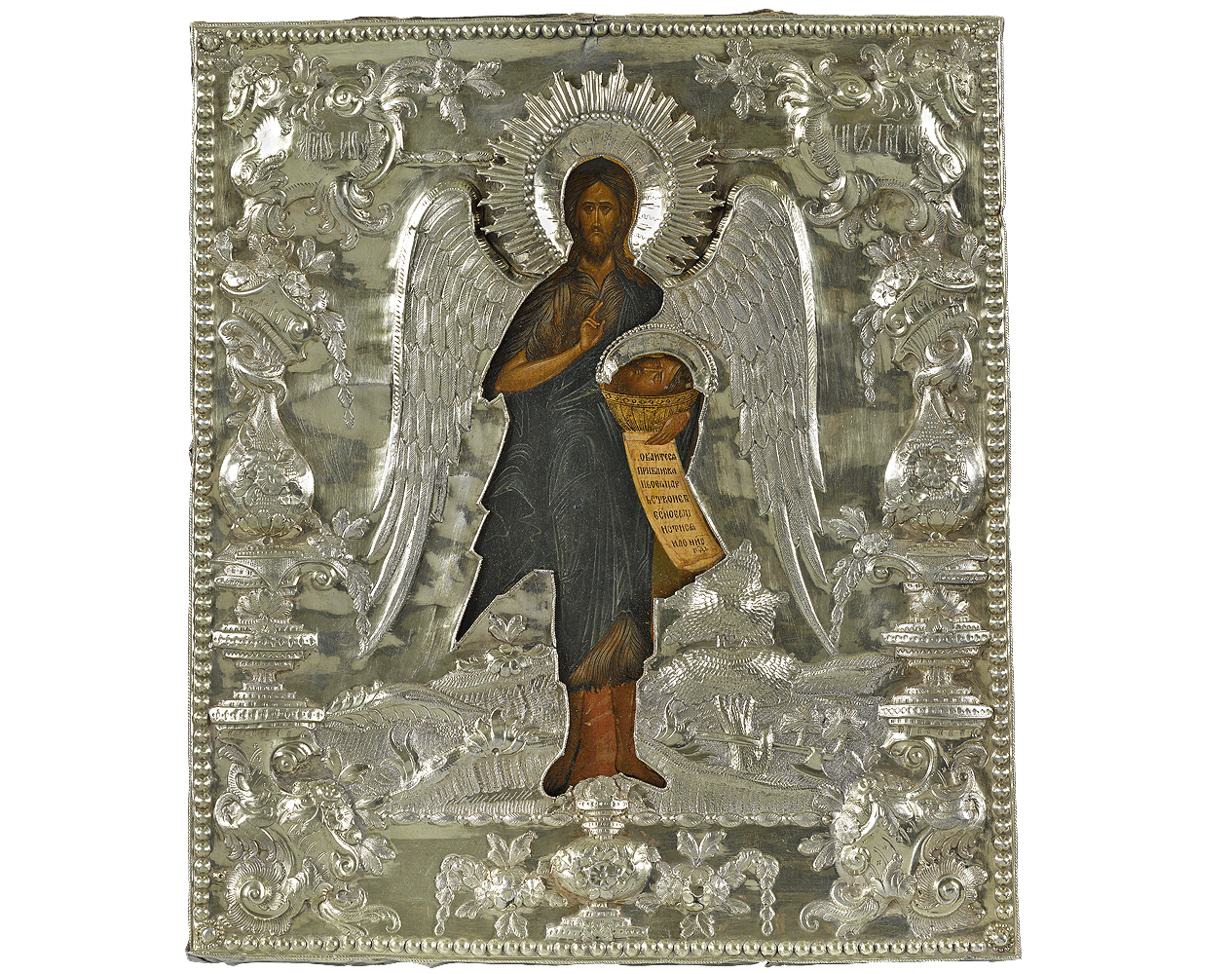

A traditionally painted 17th-century icon encased in a lavishly decorated later silver-gilt oklad repoussé in high relief with foliate border ornamented with cartouches, shells and flowers in rococo style. The icon depicts winged and haloed St. John the Baptist in the desert. The saint is represented full-length in an erect frontal pose with wings outspread, clothed in a camel hair tunic and dark green himation. In his left hand, St. John holds an unfurled scroll with an inscription written in Old Church Slavonic and a chalice with his decapitated head, the right hand is raised in a gesture of blessing. The text on the scroll reads: ‘Repent ye, for the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand‘ (Matthew 3:1-11).

St. John the Baptist is one of the most venerated Christian saints, the last Prophet of the Old Testament, the Forerunner of Christ. St. John’s life was a common subject in Western and in Eastern art. The iconographic type depicting St. John as an angel originated in thirteenth-century Byzantium. One of the earliest examples can be seen in the frescoes from Arilje dating to 1296. The frontal type was common to the sixteenth-century icons of Greece and Crete. This type was spread throughout the Eastern Church in the post-Byzantine period but was considered heretical by Western ecclesiastics.

Inspired by Christ’s description of John in the Gospels as ‘messenger’ (angelos in Greek): ‘Behold, I send my messenger before thy face, which shall prepare thy way before thee’ (Mark 1:2-4), the image of the winged Forerunner corresponds not only to his function as a messenger but also to the ascetic life of a terrestrial angel and celestial man. A 7th-century prayer by St. Germanus of Constantinople reads: ‘How shall we call thee, O prophet? Angel, apostle or martyr? Angel, for thou hast led an incorporeal life. Apostle, for thou hast taught the nations. Martyr, for thou hast been beheaded for Christ‘ (Troparion, Tone I).

The iconographic type of the Angel of the Desert, extremely popular in the Eastern Orthodox tradition, is surprisingly absent in Western art. Western ecclesiastical authorities tended to consider the depiction heretical, preferring to foreground John’s roles as an apostle and a martyr. In Russia, however, the type became the most widespread in the 16th and 17th centuries.