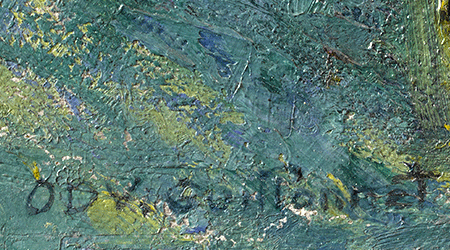

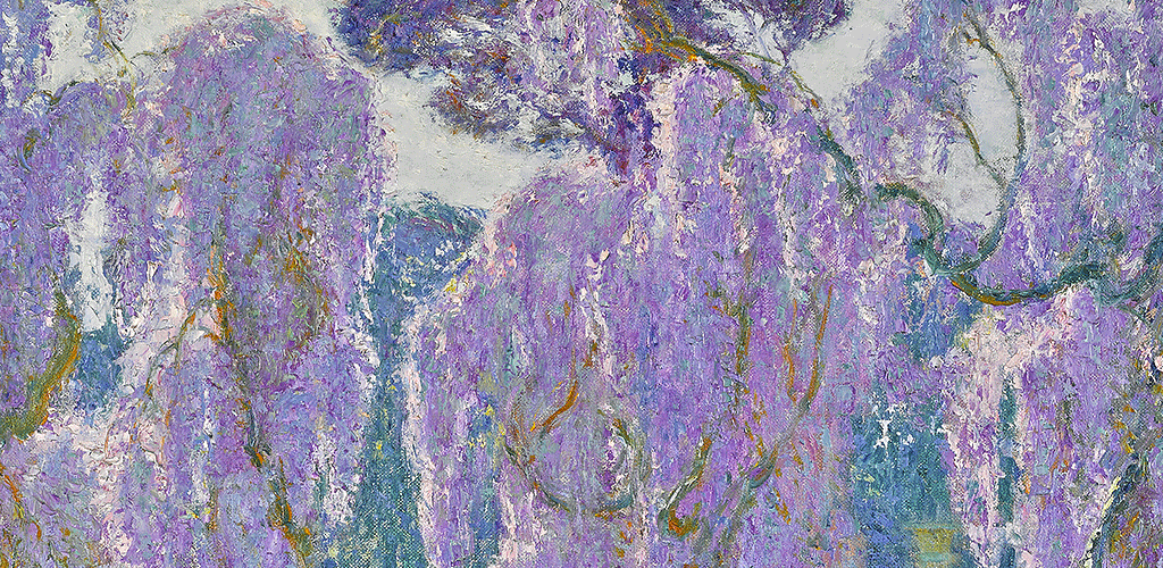

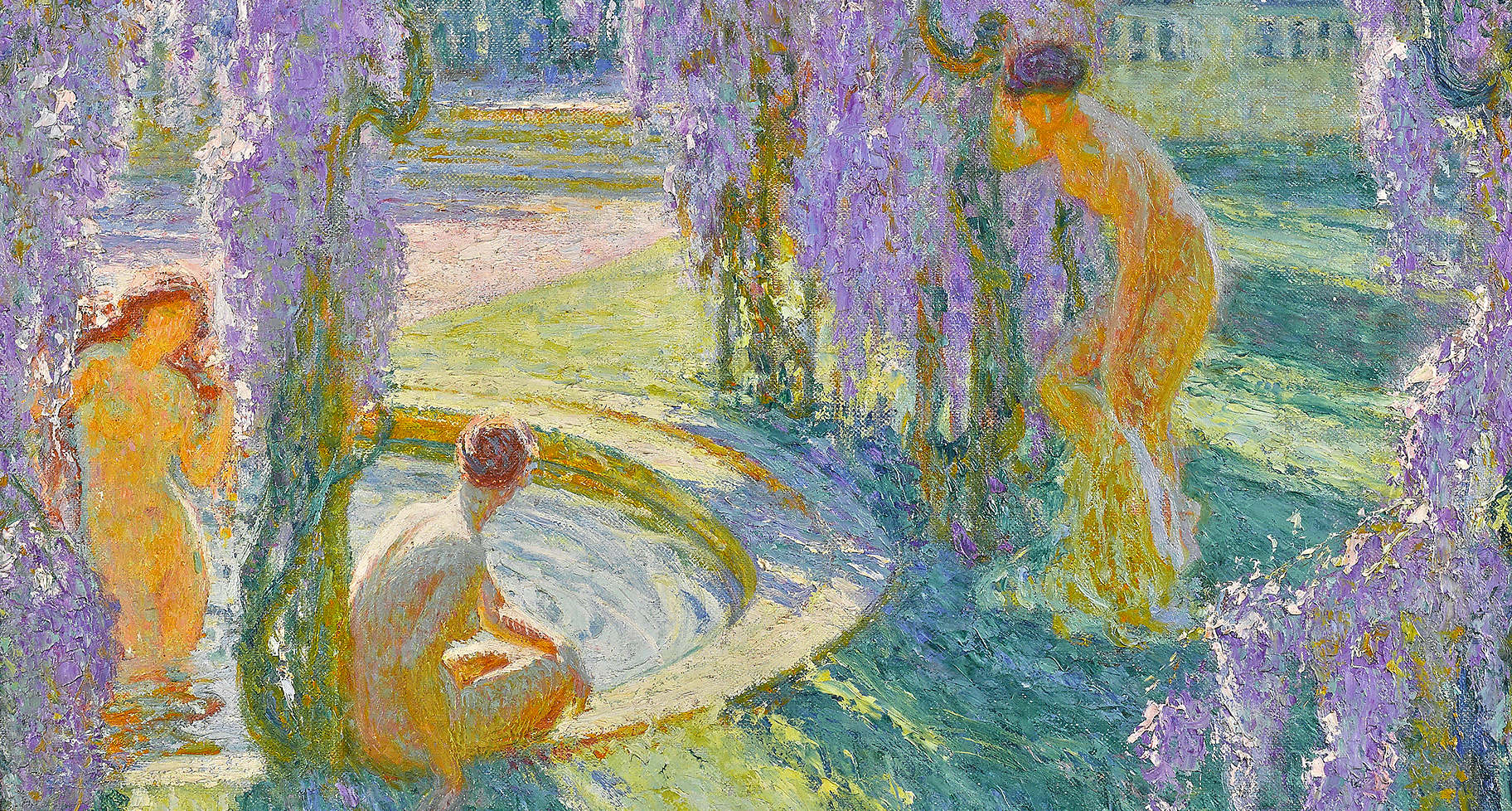

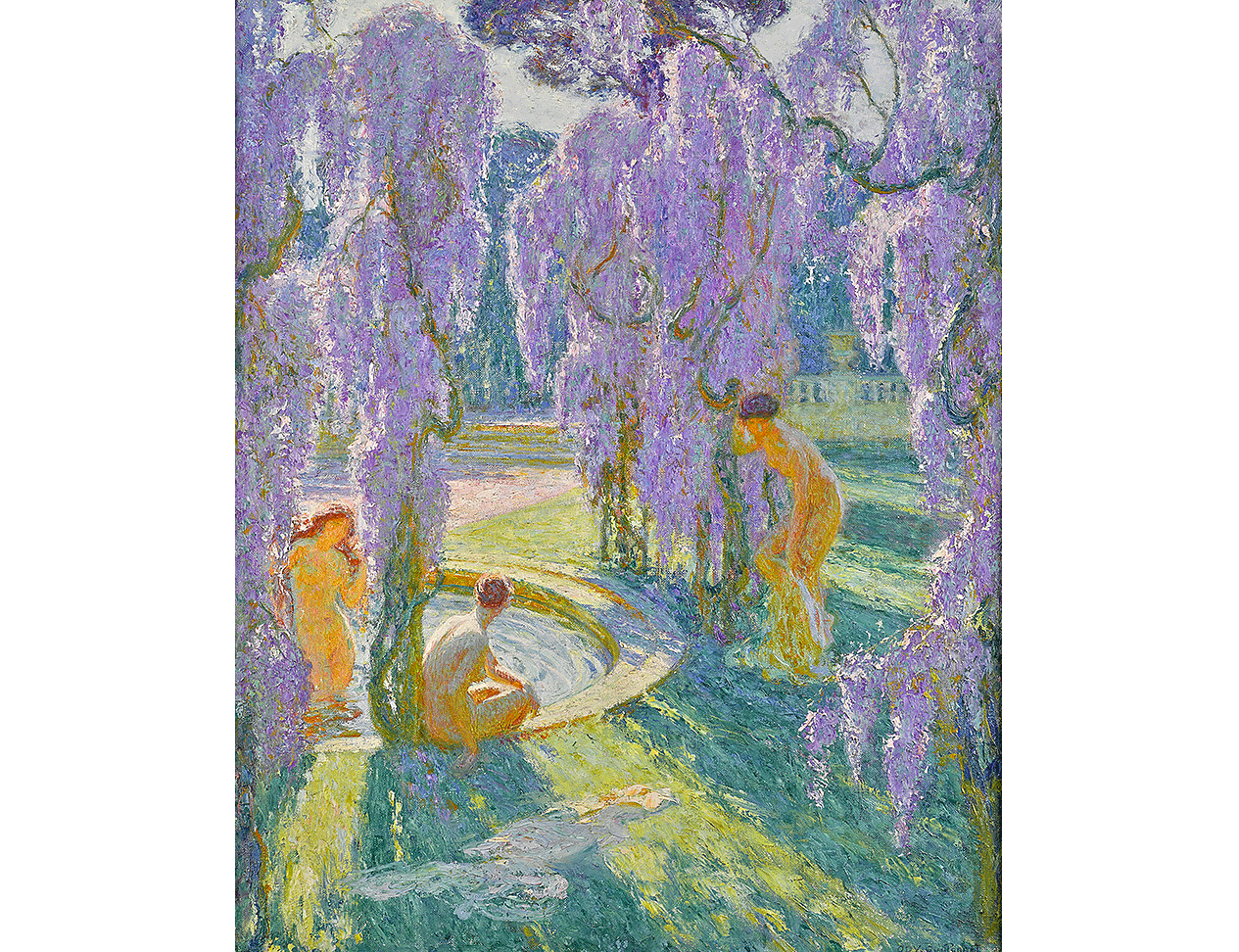

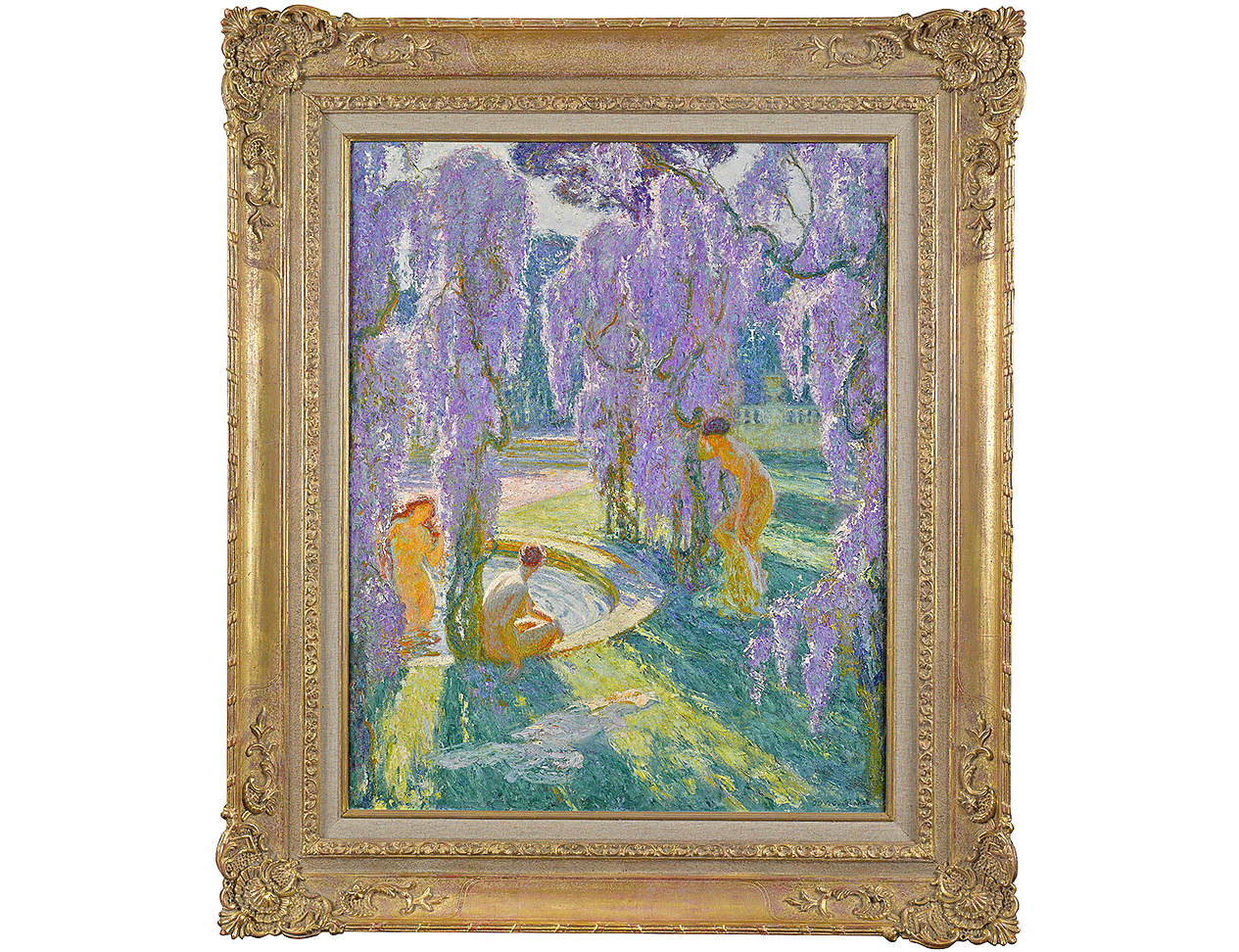

The canvas is an exquisite example of Octave Denis Victor Guillonnet’s mature style, characterised by a delicate understanding of Post-Impressionist techniques combined with idealised subject matter. Recalling both Homer’s Odyssey and the gardens of Monet, the central figures in Baigneuses Sous les Glycines resemble nymphs bathing in an Impressionist bower. The marriage of captivating subject matter and a well developed, modern style allowed Guillonnet to become a highly decorated artist in his lifetime. As we can see from the painter’s emphasis on the way light and shade affect the viewer’s appreciation of lawn, body, and blossom, Guillonnet was highly sensitive to Impressionist colour theories regarding the surprising colour combinations present in shadows.

Guillonnet was extraordinarily precocious as an artist, entering the studio of Lionel Royer at the age of thirteen and, incredibly, gaining his first medal at the Paris Salon two years later. His glittering youth was continued when he was classed Hors-Concours by the Salon at 21 years of age (which meant his exhibits did not have to be judged by the committee – his six exhibits were hung as a matter of right), and in 1901 he won the national travel scholarship, which was only awarded every two years and which allowed him to spend a year in Algeria. This proved to be a decisive turning point in his career, because he was greatly affected by the bright light and colours of Algeria, as have many artists before him, notably Delacroix. It was also in Algeria that Guillonnet developed his interest in the painting of ‘half shadows’; the Impressionists had shown that shadows contained contrasting colours and Guillonnet developed their theories.

His early mature style was symbolist, giving otherworldly connections to dreamy beach scenes or figures in a garden. Guillonnet seemed to respond to Charles Maurice’s exhortation of 1888: ‘Since our life is such a terrible affair … unable to provide us with the perfect realisation of our dreams of happiness, art will have to deck herself out in the widow’s weeds of joy.’ Then from about 1915, Guillonnet changed his style to a more strictly descriptive Post-Impressionist expression, depicting figures in gardens. The figures were either passive, as when he painted his wife Emile in one of their gardens, or active and central to the theme of the painting, as in this painting of bathers under lilac trees. Another example of Guillonnet’s use of ‘active’ figures in his work is his depiction of figures in fancy dress. He became an Official Painter of the Third Republic, and his classical training and good connections helped him to obtain many commissions for work, often of a monumental size. In addition to the many lucrative portrait commissions, important examples include those for the Hotel de Ville of Paris, 46 panels for the Venezuelan Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Caracas and the Stations of the Cross in Philadelphia.

Works by the artist can be found in major museum collections such as the Paris Museum of Modern Art, the Museums of Luxembourg, Bordeaux, Dijon, Nantes and others. He also illustrated various books, including L’Arlésienne by Alphonse Daudet.