On 25 May 2022, despite events in Ukraine, Sotheby’s London will be holding an auction to assess how things are looking on the Russian art market. I went to the pre-sale viewing a couple of times over the weekend… and saw none of the Russian faces I would normally see!

Fabergé and other Russian items are included in the auction, which is entitled Gold Boxes, Fabergé and Objects of Vertu. The number of Russian lots is modest – both in quantity and quality – compared to the good old days: just 54 items (Lots 95-148). Sotheby’s have chosen not to include paintings, porcelain, enamels or icons. There isn’t a lot of silver either. The finest, and probably most expensive, item is a Fabergé clock with garlands and green enamel (Lot 102, estimate £70,000-90,000). I have no complaints about either its authenticity or Sotheby’s valuation; a little restoration will easily eliminate some minor defects.

Lot 102, Fabergé varicoloured gold and silver-mounted guilloché enamel clock

The total anticipated value of the Russian ensemble barely amounts to £450,000. Most of the estimates are pragmatic and reflect the auction’s indifferent overall level. I hope the sale nonetheless attracts interest, and would like to draw attention to a number of items.

A total of 18 miniature eggs account for one-third of the sale’s Russian content. Six of these eggs were auctioned – as part of a necklace – by the Italian auctioneers Wannenes in Monaco on 28 July 2020. There was no mention of Fabergé in the catalogue. The hammer-price was over ten times the modest €1,000-2,000 estimate. The necklace resurfaced soon afterwards in an Elmwood’s on-line jewellery auction with a valuation of £20,000-30,000. The hammer price was not much higher than at Wannenes: £19,000. Again, the lot description contained not the merest squeak about Fabergé: so much for the eye of the Italians and British. The necklace was bought by an American punter and quickly entered at Sotheby’s – this time with the anonymous eggs granted a new lease of life as having being hatched by Fabergé.

The statement that Lot 100 is ‘probably Fabergé’ is quite amusing. The item is crude and clearly of recent manufacture – witness its excessively thick jade blade. The comparison with the delicate jade paperknife once in the Forbes Collection is laughable.

- Lot 100, Fabergé (???) Gold-Mounted Guilloché Enamel and Nephrite Paperknife, Probably Fabergé

- Lot 130, Fabergé(???) jewelled gold pendant brooch

A pendant brooch (Lot 130) is undoubtedly antique, but I would be ashamed to describe – let alone guarantee – it as Fabergé. The dubious initials KF are struck on the hairpin alone, which is hardly convincing. There is plenty of similarly re-branded Western jewellery on the market today, passed off not just as Russian but as Fabergé.

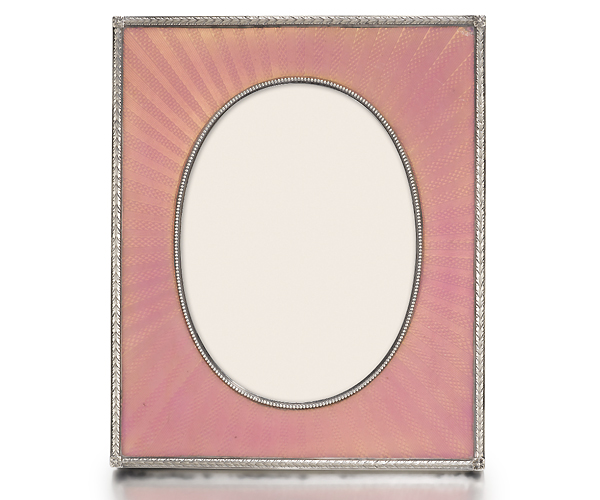

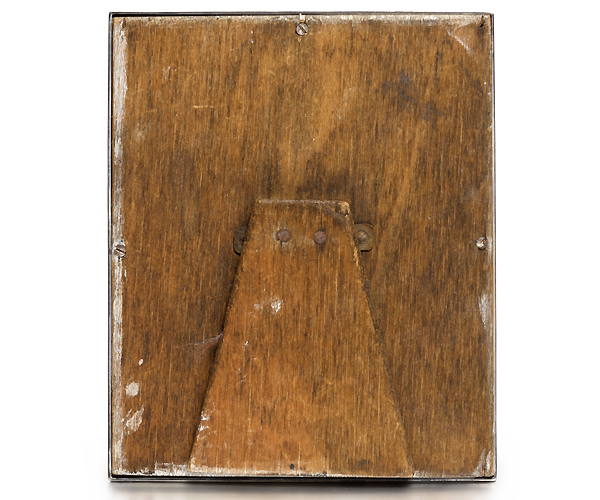

- Lot 116, Large Silver-Gilt and Guilloché Enamel Photograph Frame

- Lot 116, Large Silver-Gilt and Guilloché Enamel Photograph Frame

There are four photo frames in decent condition, 3 look okay in terms of authenticity but are all pretty run-of-the-mill (Lots 95, 103, 116) I call such things ‘entry-level Fabergé’ or ‘Fabergé for beginners.’

Lot 103 has a hideous back made by some cack-handed operator – how Sotheby’s dare propose such nonsense is beyond me. Lot 116 has a wooden back panel with new bolts or screws applied by living craftsmen; all neatly done, but Fabergé never used this type of wood. Lot 118 raises several questions: the silver back, with its lengthy inscription, is a later addition; the inscription hardly enhances the frame’s value, and reeks of fresh execution and clumsy style, and Russian just isn’t written like that; the whole frame has been completely re-gilded; and the red enamel inspires zero confidence – it shines and sparkles like new, and it most probably is.

- Lot 118, Fabergé (???) silver-gilt and guilloché enamel photograph frame

- Lot 118, Fabergé (???) silver-gilt and guilloché enamel photograph frame

A basic, mundane, white enamel Fabergé desk-clock is unlikely to arouse much enthusiasm with an estimate of £35,000-55,000 (Lot 117). Times are different: people want things that look cooler and come cheaper. A small white box is one of the cutest items in the auction – pity it’s a bit shabby and has been poorly restored (Lot 119).

Lot 119, Fabergé jewelled enamel box

Two stone figurines of a Hippopotamus and a Rhinoceros (Lots 96 & 97) are boldly and categorically identified in the catalogue as Fabergé, St Petersburg c.1900 – even though neither has ever appeared in books or exhibition catalogues. What’s more, the original boxes and invoices are missing, and there is no provenance other than a fatuous catalogue assertion that Lot 96 comes from some ‘Important East Coast Collection.’ I have never understood exactly what constitutes an ‘important collection’ – just seems like auction jargon designed to impress the naïve.

The Hippopotamus catalogue entry includes romantic detail about how the creature’s purported one-time owner, Princess Maria Kudasheva, fled Bolshevik Russia in 1919. The tale would be fine in a book about the Russian nobility, but why it should mean anything to a potential buyer escapes me. And the use of white agate is perplexing: hippos, as far as I can remember (and I’ve seen a few in the wild), tend to be a different colour.

- Lot 96, Fabergé (???) agate model of a hippopotamus

- Lot 97, Fabergé (???) jewelled aventurine quartz model of a baby rhinoceros

Such figurines were produced by St Petersburg stonecutters like Avenir Sumin, Prokopy Ovchinnikov and Alexei Denisov-Uralsky as well as Fabergé, and also traded by Bock and Morozov. Sotheby’s would be better advised – and, more importantly, more honest – to use words like ‘probably’ or ‘possibly’ when attributing these sort of items. To assert that the Hippopotamus and Rhinoceros were produced by Fabergé is irresponsible to say the least.

The Silver section (Lots 138-148) is also bereft of masterpieces, with a tedious parade of decanters and tableware. The only item worthy of attention is a gigantic, multi-kilogram jasper barometer with extravagant silver mounts (Lot 144). There is nothing Fabergé about it except the hallmark – and the estimate of £35,000-45,000 which, I suspect, is based purely on the thing’s weight: beauty and aesthetics do not seem to have been taken into account. Either that or Sotheby’s failed to inform the vendor that the price of Fabergé is not determined by the meter or kilogram. Times were when this sort of nonsense fetched big money. Not any more.

- Lot 144, Fabergé large silver-mounted jasper aneroid desk barometer

- Lot 148, Three-piece silver-gilt tea service

Lot 148 is a cheap tea-service worthy of Portobello or Moscow’s Izmailovsky flea-market. It has nothing to do with Fabergé: the KF mark refers to Karl Fend. Tatiana Muntyan catalogued the master’s items in the Moscow Kremlin in her Works of the Leading Jewellery Companies of the 19th & Early 20th Century: Fabergé (pp 348-54). Strange that Sotheby’s top expert should be unfamiliar with the Moscow Kremlin’s Fabergé catalogue! It’s worth flicking through the odd book from time to time: you never know if you’ll come across something useful. Knowledge itself is power.

Tatiana Muntyan, Works of the Leading Jewellery Companies of the 19th & Early 20th Century: Fabergé

Other items are hardly worth mentioning. We’ll see what happens tomorrow and report afterwards.