Covid must have been a wonderful pretext for auction houses to stop printing catalogues. I love printed catalogues! They’re great for reference and information, etc. I hope this ill-conceived ‘new beginning’ of Online Sales Only is fleeting, and that catalogues will re-appear soon.

PICTURES

- Lot 3, Dmitry Levitsky, Portrait of Emperor Paul I. Christie’s

- Dmitry Levitsky, Portrait of Count Ilya Andreevich Bezborodko. Sotheby’s

A couple of Imperial portraits set Christie’s ball rolling. A small, waist-up depiction of Tsar Paul I ascribed to Dmitry Levitsky (Lot 3) has me puzzled. Christie’s term it ‘a recent discovery’ and list its first known owner as ‘Colonel Andrei Kvitka (1849-1922).’ Who the hell was he? (‘a man of many talents and interests’ boast Christie’s meaninglessly). The painting is not signed. Copies of this portrait, of varying sizes, were dispatched to ministries and to Russian embassies around the world. The catalogue does not offer a convincing account of the work’s history – and I’m not convinced it’s by Levitsky, as opposed to a decent copyist. The £700,000-900,000 estimate is more than ambitious. A resplendent portrait of Count Ilya Bezborodko, double the size and with a stellar, unimpeachable provenance and exhibition history, turned up at Sotheby’s last December yet barely squeaked past its £350,000 low-estimate. I bet the only bidder was fighting himself, and got hammered by the reserve.

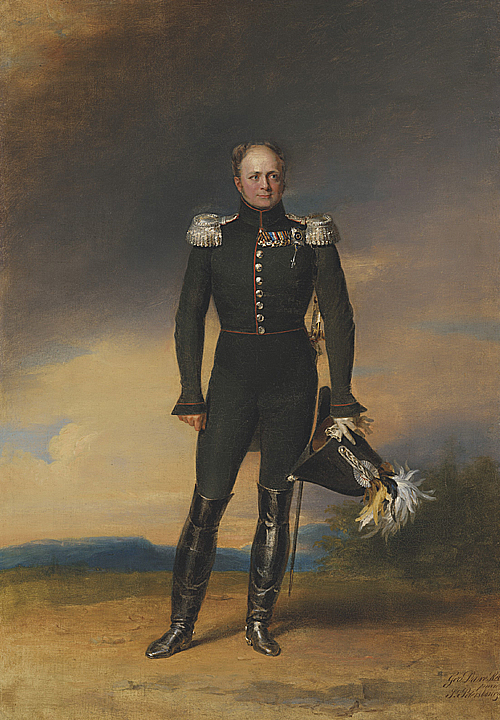

Lot 2, George Dawe, R.A., Portrait of Emperor Alexander I. Christie’s

It may be just one of several versions, but a full-length George Dawe Portrait of Alexander I (91 x 63 cm) looks impressive even though it’s not very big (larger Dawe portraits have appeared in the saleroom now and again in recent years). This one was commissioned as a gift for Pushkin’s pal Juan Miguel Páez de la Cadena y Seix (1772-1848), the Spanish Ambassador, and remained with his descendants until 2019. Dawe worked in St Petersburg 1819-28, and is best known for his series of 336 portraits of Russian generals that line the purpose-built 1812 War Gallery in the Winter Palace. Alexander sat (or rather stood) for him in 1823 (Lot 2, est. £150,000-250,000).

There’s a small, perfunctory Ayvazovsky Shipwreck (Lot 1, est. £30-50,000), and a boring, monochrome Pokhitinov beachscape, daubed at De Panne on Belgian’s North Sea coast (Lot 39, est. £30,000-50,000). Pocket-sized Pokhitonovs plague London auctions almost as much as Harlamoff’s moping maidens. The one here (Lot 42) has a basket of apples in her lap and an absurdly ambitious £100,000-150,000 estimate. Just as tedious are 27 studies by Maria Yakunchikova (1870-1902) ‘never before seen on the market,’ each priced in the £2,000-8,000 range (Lots 12-38). I thought Christie’s didn’t accept anything below £10,000! Sell ’em as one lot, for Christie’s sake!

Serov’s Zaporozhian Cossacks is a decent size (80 x 98cm), but undated and looks unfinished. When you buy a Serov you want one that screams Serov! at you from across the room. This one merely murmurs (Lot 45, est. £300,000-500,000). But there’s an assertive Gorbatov, The Invisible City of Kitezh (1913) – inspired by the Rimsky-Korsakov opera that premiered at the Mariinsky in 1907. This Gorbatov picture was auctioned twice in the 1980s but is a good, early, eye-pleasing work. I can’t really say anything bad about it except for its huge, hardly achievable estimate (Lot 11, est. £350,000-550,000). Another Gorbatov, his pretty Golden Autumn (1924) has a much more reasonable estimate (£80,000-120,000) that should give it a better chance of squeaking through (Lot 58). His later, honey-toned view of Jerusalem (1935) will most likely find a buyer because of its geography (Lot 61, est. £70,000-90,000).

I’m not a big fan of Korovin. His 1919 On The Terrace is nothing exciting – and yawningly similar to many female-figured Korovins we’ve seen in the past (Lot 43, est. £400,000-600,000). The less said about Christie’s second Korovin, a horrible late effort, the better (Lot 55, est. £8,000-12,000).

I don’t like Saryan much either, so I can understand why he foisted his sketchy View of Mount Ararat (1923) on Maxim Gorky when the moustache-man visited Armenia in 1928 (Lot 46, est. £200,000-300,000). The majority of the paintings in the sale hardly merit comment. A late work by Sergei Chekhonin, a Still Life in gouache-on-card, is dated 1931; Chekhonin died in 1936. The picture (Lot 44) is quite OK – more because of the artist’s name than the work itself, which sold at Sotheby’s years ago for ten grand or so, against a measly estimate of £4,000-6,000. I don’t remember Chekhonin yielding prices of the magnitude Christie’s are hoping for (£250,000-350,000). I can’t see it getting there.

Lot 48, Robert Falk, Trinity Lavra of St Sergius. Christie’s

A two-sided canvas by Paul Kotlyarevsky features A Man Reading and Shovelling Sand by the Seine – rare, pretty Cubist images, but how do you hang the thing (Lot 47, est. £70,000-90,000)? The next lot, Falk’s Trinity Lavra of St Sergius (1921), features one of Russia’s holiest sites. The picture is colourful but boring and devoid of life; it reminds me of primitive lubok painting. The estimate brings up memories of yesteryear. It appears that Christie’s and the owner somehow expect a windfall (Lot 48, est. £700,000-900,000).

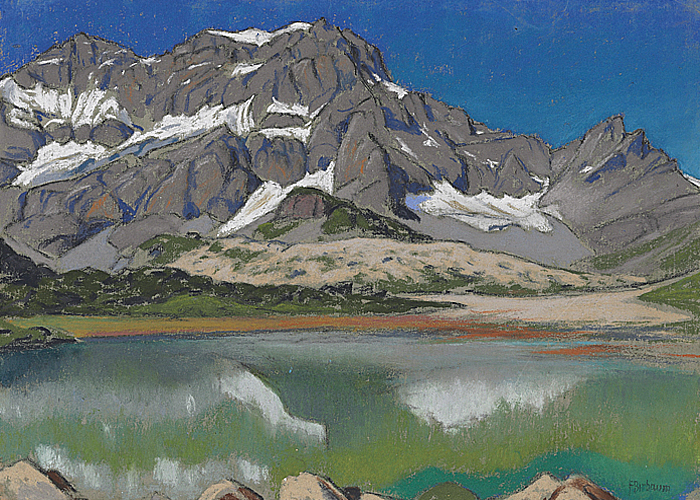

Lot 66, François Birbaum, Mountainous landscape; and Haystacks. Christie’s

Another double-sided work is provided by Fabergé’s onetime Head of Design, Franz Birbaum (1872-1947). It has a Mountainscape on one side and some Haystacks on the other, both done in pastel – probably in Birbaum’s native Switzerland in the 1920s (after Franz had changed his first name to the less Germanic François). There is a clear stylistic influence of Birbaum’s compatriot Vallotton, and the work was formerly owned by Carl Fabergé’s Swiss-based great-granddaughter, Tatiana. I reckon Christie’s should have shoved it in the Fabergé section (Lot 66, est. £2,000-3,000).

FABERGÉ

Lot 136, Gem-Set Silver-Mounted Ceramic Vase The Mounts Marked K. Fabergé With Imperial Warrant, Moscow, Circa 1912. Christie’s

Christie’s are offering over fifty items by Fabergé. The most expensive – as far as Christie’s estimates go – is a gem-set ceramic vase with Pan-Slav silver mounts (Lot 136). I don’t like it – and I can hardly see it making £150,000-200,000, despite an inscribed dedication marking the 1912 Moscow visit of American horse-breeder Charles ‘Doc’ Tanner (1865-1955)… who (as Christie’s omit to mention) was inducted into the New York Harness Racing Museum’s Hall of Fame in 1978. I’d have divided the estimate by two – and that’s being generous.

Lot 119, Guilloché Enamel Silver-Gilt Photograph Frame, Marked Fabergé, With The Workmaster’s Mark of Victor Aarne, St Petersburg, 1899-1904. Christie’s

The three best Fabergé frames in the sale deserve a serious look, although all three have deficiencies. The first (Lot 119, est. £80,000-120,000) – a rare X-shaped frame with coveted imperial provenance: it was gifted by Nicholas I’s grandson Grand Duke Michael in 1901. But its condition leaves a lot to be desired. The frame was re-enamelled in many spots many years ago. Its state prior to the workover is in the 1986 Munich exhibition catalogue (G. von Habsburg, Fabergé, Kunsthalle of the Hypo Kulturstiftung, Munich, 1986, p. 244, no. 487).

The second (Lot 120, est. £100,000-150,000) is a deep blue and white guilloché enamel Perchin frame that we’ve already seen a few times, (Lichtenstein Collection, Kazan Collection). It contains a portrait miniature of American socialite Edith Rockefeller McCormick. What a shame that otherwise such a dainty and exquisite object is so badly scarred with a deep abrasion to enamel in the centre right.

Lot 107, A Large Jewelled And Enamel Gold-Mounted Obsidian Model of an Elephant and Castle Engraved Fabergé, with The Workmaster’s Mark of Michael Perchin, St Petersburg, Circa 1890, Scratched Inventory Number 52383. Christie’s

The scarlet guilloché enamel frame by Perchin (Lot 109, est. £18,000-22,000) also causes a bit of a problem. And not because of the frame itself or its vibrant colour, but because it contains a miniature portrait of Tsar Nicholas I, who lived 50 years before it was made. Whoever married the frame with the miniature needs to look a little deeper into Romanov history.

An elegant, castle-topped elephant carved from obsidian, also by Perchin, looks very interesting – well, that’s my preliminary opinion based on everything about it being hunky-dory (Lot 107, est. £70,000-90,000).

- Lot 103, A Gem-Set, Guilloché Enamel and Two-Colour Gold-Mounted Nephrite Bell Push, Marked Fabergé. Christie’s

- Silver-Gilt, Gold and Enamel Bell Push, Marked Fabergé. Ruzhnikov Collection

- Silver-Gilt, Gold and Enamel Bell Push, Marked Fabergé. Ruzhnikov Collection

I have far less confidence in a gold and guilloché enamel bell push on a nephrite base (Lot 103, est. £20,000-30,000). I cannot believe Fabergé masterminded such a hideous design – it’s crudely made, the gold garland is not straight, and the piece displays nothing like the finesse of two Fabergé bell pushes in my own collection. Maybe it’s been over-zealously restored, or God knows what else.

There’s a string of the Fabergé brooches and egg-pendants that turn up in every sale and appear to travel to and fro between the London auction houses. An icon of Christ Pantocrator with an oklad by Rückert is a sorry reminder of a very similar silver-gilt and cloisonné enamel icon that I bought twenty-odd years ago at a Shapiro auction in New York – but with which my ex-wife subsequently and callously absconded, and later had sold (Lot 161, est. £30,000-50,000).

OTHER ITEMS

Lot 182, Imperial Porcelain Vase, St Petersburg, Period of Nicholas I. Christie’s

Christie’s have another large porcelain vase worth looking at by specialist collectors: a 3ft tall Nicholas I Imperial Vase painted with a Serenade after 17th century Dutch artist Jacob Ochtervelt (Lot 182, est. £200,000-300,000). On a quite different scale is a charming little gold and cloisonné enamel circular scent bottle by Hahn (St Petersburg, c.1890), apparently with its original, fitted red leather box (Lot 197, est. £6,000-8,000). The provenance is off-beat: the item, say Christie’s, was presented to the Chinese scholar Weng Tonghe (1830-1904) in Peking by the Russian Ambassador in 1897.

Lot 221, A Silver-Gilt Cloisonné Enamel Casket, Marked P. Ovchinnikov. Christie’s

On the Icon front, there a few nifty numbers with enamel – quite pretty but nothing particularly rare. Then comes the usual smattering of this and that. There are some nice enamel lots by Ovchinnikov: a silver and champlevé enamel caviar set (Lot 218, £25,000-35,000) and, in cloisonné enamel, a casket (Lot 221, est. £18,000-22,000) and cute little kovsh (Lot 230, est. £8,000-12,000).

I’m tired of looking at the massive, 1870s Sazikov parcel-gilt silver punch set that has been on the block more than once in the last 15 years (Lot 204, est. £220,000-280,000) – I’m not sure if the owner remains the same, and just doesn’t get it that the bloody thing is not worth as much as he wants; or if the punch set keeps getting shunted around between members of the trade.

The sale ends with the usual ‘Soviet Propaganda’ plates. The term ‘Propaganda plate’ implies strident slogans, so why on earth have Christie’s catalogued a plate painted with a sailor and his high-booted floozy, striding along the Neva, as a ‘Soviet Propaganda plate’ (Lot 252, est. £15,000-20,000)?

Christie’s are also seeking to offload a white porcelain ‘Soviet Propaganda’ inkstand (c.1925), incorporating a bust of Lenin (Lot 242, est. £2,000-3,000). Yuk! Images of Lenin and Stalin make me vomit. In Germany selling sculptures of Hitler and his henchmen is a criminal offence. How come Lenin and Stalin deserve better?