Christie’s 305-lot on-line auction, which ran July 1-21, was of very average quality, and had only five prices of over £100,000 (times were when they’d have had four of five prices of over a million!). Two of those six-figure sales were for paintings: an Arkhipov Peasant Girl and a Vera Rokhlin View of Tbilisi. Both made £250,000. For me, though, the outstanding picture was a market-fresh view of the Gulf of Finland by Fyodor Vasiliev, the gifted landscapist who died at 23, and whose work hardly ever appears at auction. At £75,000 it was a giveaway.

Fedor Vasiliev, Gulf of Finland

I wrote in my auction preview that clients are ready and willing to spend serious money – even on-line – on serious material, and two of the high-quality items I singled out duly soared over double-estimate: a Rückert kovsh with an en plein miniature, to £118,750; and an 1832 Imperial Porcelain military plate, featuring a Cossack Trumpeter (1832), to £106,250. I also liked the silver/enamel photograph frame by Sazikov, shaped like a horse’s yoke, that sped past its £18,000 top-estimate to £25,000. But a second Imperial Porcelain military plate, showing a Hussar and dating from 1841, limped to £23,750 – which shows just how erratic the market can be.

A Cossack Trumpeter Plate by The Imperial Porcelain Factory

A cloisonné and en plein enamel silver-gilt kovsh

Top porcelain price was £150,000 for a Sovnarkom propaganda plate from 1921 (est. £20-30,000). I’m no fan of Soviet items, but I suspect the cheerful floral patterning of this particular plate transcended its political message. The same could probably be said of a 1921 plate by Alisa Galenkina embellished with the lugubrious monochrome features of Maxim Gorky – a fine author, but too much of a Communist fellow-traveller for my taste.

A soviet porcelain plate

The item I labelled the sale’s ‘one decent-looking piece of silver,’ a samovar made by Kurlyukov in Moscow around 1890, cleared top-estimate on £32,500. The silver item to which Christie’s granted the highest pre-sale estimate – a 1747 tankard marked Boris Gavrilov touted at £20,000-30,000 – was bought in, as I feared. A ridiculous mob of ‘table articles’ in Tula steel (est. £4,000-6,000) went nowhere either. But the rare bronze I drew attention to – a seated figure of Peter the Great by Alexander Opekushin, cast by Sokolov around 1872 – attracted plenty of interest, reaching £40,000 against a top-estimate £30,000.

A parcel-gilt silver samovar

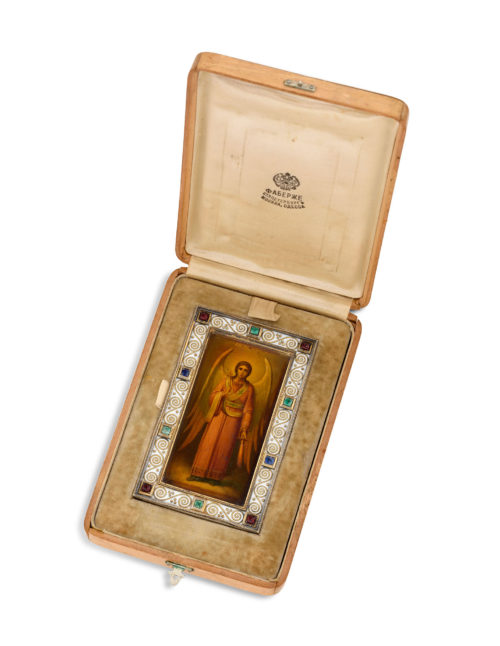

The sale’s three-dozen lots of Fabergé were of the bits-and-bobs variety, totalling a modest £300,000. Two-thirds of them found takers. A gold-mounted guilloché enamel carnet de bal by Wigström sold just past high-estimate for £35,000. Top Fabergé price was £40,000 for a gem-set silver-gilt icon of a Guardian Angel by workmaster AP (Alexander Petrov in Christie’s opinion). As I predicted, the nothing-to-it Wigström desk clock failed to approach its outrageous £50-70,000 estimate, and was bought in. So was the yellow Perchin photo-frame I once owned, which Christie’s were hoping to propel to £20,000.

A Gem-Set and Enamel Silver-Gilt Icon of a Guardian Angel by Fabergé

Forecasting auction results is no easy task, so commiserations to my picture-dealer pal James Butterwick for predicting (on his Russian Art & Culture website) that a Pasternak Still Life would deliver ‘a £100,000-plus result’ (it fetched £87,500) and promising that a Bakst costume-design for Sadko – ‘a right belter’ – would ‘hit £70,000’ (it fetched £27,500).

James and I both agreed, though, about the utter inadequacy of Christie’s mixed-up lot presentation – James explaining, in his colourful Old Etonian prose, that he was ‘having to perform gyrations in reading this damned site.’ On the other hand, I’m baffled by his fulsome praise of ‘a really good sale packing quite a punch’ – James must have been at the punch all afternoon when he came out with that pronouncement!

No, this sale was pathetic: little more than bric-à-brac, much of it consigned by the trade. I’ve never seen Christie’s put together a weaker Russian Sale – and neither has the market. The auction brought just £3.3 million, the lowest total for a Christie’s Russian Sale in living memory – and over £8m less than their previous sale in November 2019. £8m, incidentally, was precisely the amount posted by Sotheby’s sale this Summer… which proves that life remains in market, coronavirus or not!